ELUL

When Moses descended from Mount Sinai and saw the Hebrews celebrating around the Golden Calf he broke the Tablets of the Law and he and the tribe of Levi slew the idolaters. He ordered the people to melt the idol, grind it into dust which was then mixed with the drinking water and forced the Hebrews to drink of that mixture. He ascended once more the mountain to plead for God’s forgiveness which was granted to the people of Israel. On Rosh Hodesh Elul, Moses went up Mount Sinai with the second set of Tablets and remained there forty days and forty nights, descending from the mountain.

Since it is during the month Elul that God reconciled with His people and forgave its apostasy, the rabbis therefore enjoin us to look into ourselves and purify our souls in anticipation of the Day of Judgement.

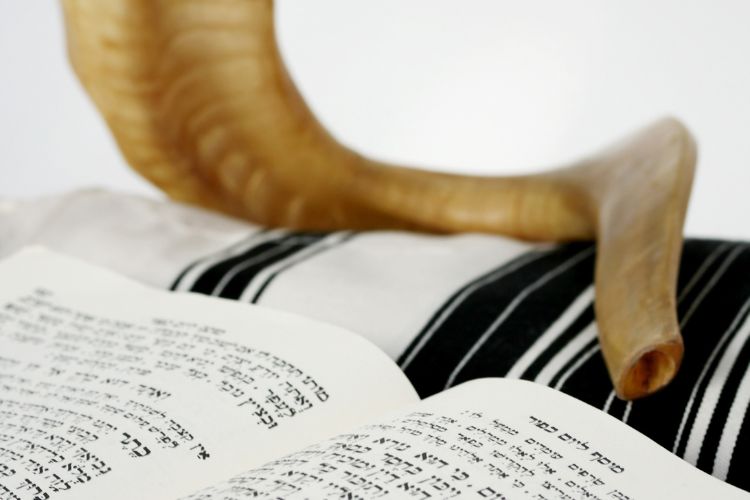

Penitential prayers or Selihot (from the root word selah, meaning forgive) are recited every day. From the second day of Rosh Hodesh Elul until the eve of Rosh Hashana, the four sounds of the shofar are blown, once in remembrance of our ancestors for whom the shofar was blown daily to warn them not to err again. The shofar call to repentance of yesteryear stirs us still today.

To underline the importance of the recitation of Selihot, the rabbis make the following analogy. A poor man was once invited to the King’s palace. His joy was mitigated with sorrow as he did not have any garment to wear but the one on his back. So he washed it carefully, and finding it still unworthy of his host, he washed it again and again until satisfied that no spot could be found he felt ready to go see the King. Such is the purpose of Selihot, a cleansing process to enable us to come closer to God.

AN AMAR FAMILY TRADITION (Morocco)

During the month of Elul, all the children of our neighborhood practiced blowing the shofar. Some because they were going to blow it at Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur services and most of us just for the fun of it.

My father who usually conducted the High Holidays Services at his Grandfather Baba Messod’s synagogue would practice as well. He would pull out of his armoire THE shofar which was carefully wrapped in soft cloth and lay it on top of the dining-room sideboard.

We were of course told not to touch it, but who could resist its soft patina and mystery? I would take it and blow discordant sounds out of it to the reprobation of my mother and grandmother in whose eyes my action had been one of defilement that had to be reported to my father.

Sometimes to appease his mother, I was punished for my infraction. Perhaps weary of my determination to blow the shofar, one year, he brought home several ram’s horns and announced that we were going to make our own shofar. We recoiled at the sight of that strange object that clearly evoked its origins.

Enthusiastically my mother took the horns from my father and put them in a large pot of boiling water. We watched her scoop with a large ladle the foam that would raise to the edge of the pot, and as only a mother knows, after a while she declared them done. One at a time she pulled the horns out of the water and with a knife scraped out some matter attached to the inner wall.

She then cut off the narrow end forming the mouthpiece and lifting the horn to the light she cleaned its innards once more. She returned it to the water, and after a while took it out, shaped it in a graceful curve and let it to dry. Ignoring the roiling water and the stench she fashioned a shofar for each one of us.

It was the last time I touched my father’s shofar and for that matter any shofar.