Translated by R. Haim Ovadia

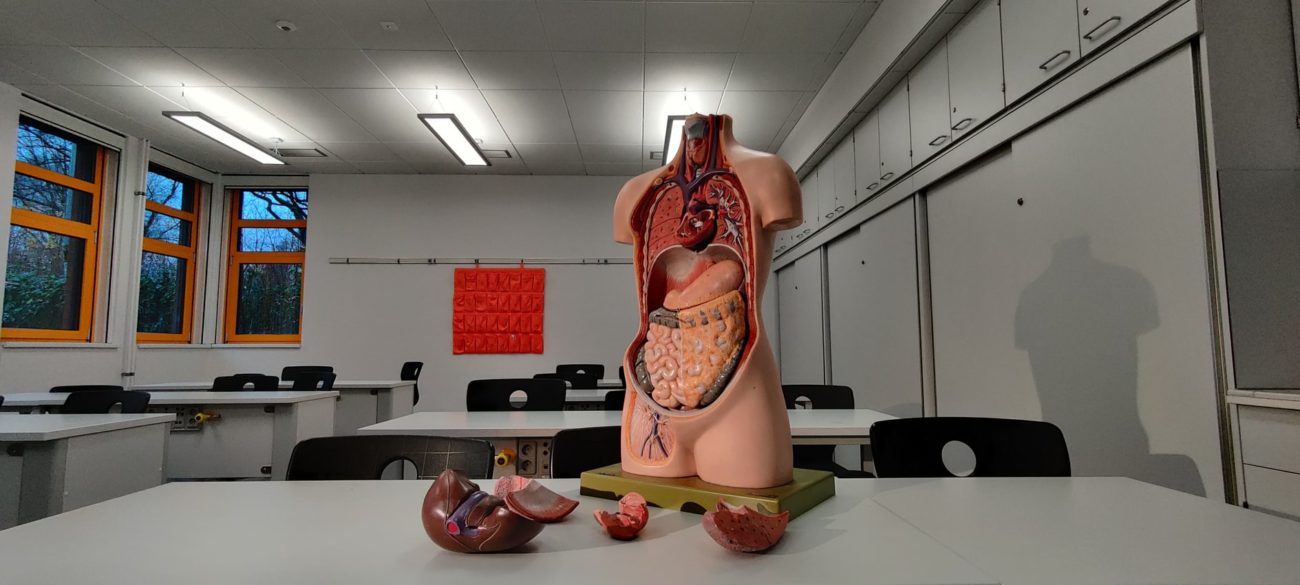

Organ Transplants and Autopsies

The following is a translation of the groundbreaking response by Rabbi Yossef Messas regarding the permissibility of corneal transplant, which is performed after the donor’s death. By the time of Rabbi Messas’ passing, in 1974, heart transplantation was still in its inception, but a careful reading of this response shows the encompassing and humane approach of Rabbi Messas and leaves no doubt that he would allow all transplants.

Cornea transplant, for the benefit of the living:

A new light has shone in our time on all branches of wisdom and science, including medicine and surgery, which found a way to remove parts of the eye from a person who passed away and transplant it in a blind’s person eye, delivering him from darkness to light, enabling him to see clearly, to learn and teach, to be productive either as an artisan or a merchant, to provide for himself and his family, and possibly to benefit the People of Israel and the whole world through the knowledge he gains. I was asked by the supreme court of Rabat if it is allowed to remove these parts from the eyes of a Jew.

Answer: There are three possible arguments against doing so:

1. Disrespect to the deceased; 2. Deriving benefit from the dead; 3. Not bringing the removed part to burial. Let us expand a bit:

1. Disrespect for the deceased: in my humble opinion this is not a concern at all, since the deceased feels nothing. Now, it is true that Rabbi Yom Tov Lipman Heller writes that the soul suffers when the body is disrespected even though the body feels nothing, and that this is also the opinion of Iyyun Yaakov, these are all assumptions and guesses attempting to provide commentary on Aggadah (non-halakhic texts). They base their remarks on the verse “his flesh will be pained, and his soul will mourn”, but the verse is a poetic statement, as is the rest of the book. Or, as the commentator Metzudat David explains, it refers to the pain one suffers while still alive, which hurts the soul as well. After one dies, however, the reality is that he feels and knows nothing as is described in the previous verse: “his children will grow mighty and he will not know, and when they deteriorate he will not be aware.”

In my humble opinion the disrespect is not towards the deceased, since the body is like a stone which has no sense or feelings, while the soul ascends to the place of reward and punishment, having no attachment whatsoever to this world. As it is written “the dust shall return to the earth as it was and the spirit shall return to God who has given it [to us]”. The word “dust” refers the body as it is written “for you are dust and to dust you shall return”.

The Midrash describes the prayer of Yehoshua bin Nun, in which he addresses Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, saying “’my forefathers beg for mercy for me.” The authors of the Tossafot point out that it is written elsewhere that the dead, including the patriarchs, know nothing about the events and occurrences in this world. They answer that the dead only know of issues mentioned by someone in his prayer, of which they are notified [see my book Mayim Hayim, 206].

The disrespect then is towards the living, who are tortured by observing a human being, just like them, in a state of disgrace. Similarly, we find a discussion in the Talmud whether burial is to prevent disgrace, or to provide atonement.

The Talmud asks what would be the implication [נפקא מינה] of following one reason or the other, and answers that it would matter in the case of a person who commanded his relatives not to bury him. If burial is done to prevent disgrace, he does not have the authority to issue such a command. Rashi explains that the disgrace is to his relatives and therefore he cannot prevent his own burial and cause his family shame or pain. Rashi’s argument is that even though that person feels no disgrace after his death, his relatives suffer upon seeing a dear one lying down as if discarded in the marketplace. The authors of the Tossafot wrote similarly and concluded that the deceased feels no disgrace. Rabbenu Yaakov ben Rabbenu Asher rules as follows regarding this case: “Even if the one who requested not to be buried has no relatives, we disregard his request because not burying a person causes disgrace to all who are living and not only to one’s family.” His ruling is based on that of Maimonides. For the same reason, Rabbenu Yaakov rules that it is forbidden to leave a dead body without burial, as Rabbi Yossef Karo also comments.

In the case discussed here, the operation is done by trusted and committed surgeons in closed quarters. The sole intention of the surgeons is to improve the health of the living, and not, God forbid, harm or disgrace the deceased. We can therefore conclude without doubt that it is a great merit for the deceased that the body which was about to deteriorate and fade, has been used for a Mitzvah, and this will give him peace of mind in the World of Truth. The rabbis have similarly explained the verse “God prefers charity and justice over sacrifices”, saying that even if the charity was done without one’s knowledge it is still better than sacrifices, for example, if one lost a coin and a poor man found it, or even if the coin was stolen by the poor man who used it to sustain himself. In the case of a corneal transplant, a great act of charity was performed with one’s body without his knowledge, and God will reward him for it.

Now, even if the organ will be transplanted from the eye of a deceased Jew to the eye of a living non-Jew, there is nothing wrong with it, since today we are the givers and tomorrow the receivers and so on. We thus establish reciprocal relationship, and obviously, they will give more since they are the majority. Also, by doing so we show the love to all human beings, regardless of religious affiliation, since we are all God’s handiworks. God is hurting, as if it were, even for non-Jews who die, as the Midrash says that God refused to let the angels sing their morning praise to Him while the Egyptians were drowning. For that reason, the rabbis established the reciting of a shorter Hallel on the seventh day of Pesah, as they wanted to promulgate the concept of love to all humans, non-Jews and Jews alike. This concept is even more applicable today, when all nations know God and have faith in His uniqueness and Divine Providence. Maimonides, in his commentary to the Mishna, warns against misleading or cheating non-Jews. He referred to Medieval Times, and how much more so we must apply his warning to the nations today, whom we use as doctors and barbers. They are also conducting their business ethically, often, I am embarrassed to say, more than the Jews.

We can now conclude that if the eye of a deceased Jew will be transplanted to a living non-Jew, it will be as if the Jew has physically performed a Mitzvah which will comfort his soul in the world to come, and would not cause pain or disgrace. Similarly, the Rashba [Rabbi Shelomo ben Adret] ruled in his Responsa: “all actions performed to guarantee a faster decomposition of the flesh, in order to carry the deceased to his preferred burial site, are allowed. There is no pain or disgrace, since the dead flesh does not feel even a scalpel, let alone lime. The process of embalming included the dissection the body and the removal of internal organs, without concern over pain or disgrace.”

It is true, however, that we have a contradictory opinion by Rabbi Shemuel Landa, which was printed in his father’s Responsa. The case was presented by a scholar from London, of a man who died during surgery for gallbladder stone removal. The rabbis of the city were asked if the doctors could posthumously remove skin from the area of the surgery in order to better understand the problem, and to gain knowledge which might help them in future cases. Their answer was not unanimous, as some were in favor and some opposed. Those in favor relied on the Rashba Responsa, as well as on the argument that saving human life overrides all other prohibitions of the Torah.

Those who opposed relied on the case mentioned in the Babylonian Talmud of an orphan who sold his father’s possessions and then died. His heirs appealed the validity of the sale, claiming that the orphan was a minor at the time of the deed, and wanted to exhume his body for examination. Rabbi Akiva overruled their request, telling them that they are not allowed to disgrace the body.

This argument was refuted by those in favor because the Talmud concludes that even though the heirs are not allowed to conduct the examination, the costumers should have been allowed to conduct it. The Talmud eventually forbids the examination on the grounds of it being unreliable, as it is determined by the existence of pubic hair, which deteriorates posthumously.

When the matter was presented to Rabbi Shmuel Landa, he rejected the arguments of those opposed to the operation, but then concluded with the following statement:

I wrote my arguments from your point of view, which sees the operation as having a life-saving potential, but if it is true that there is even the slightest chance of saving a life with this procedure, I wonder why you need such lengthy discussions, since it is well known that we are allowed to transgress Shabbat for a remote chance of saving a life. The answer is that we only consider the possibility of saving a life if the person in question is in front of us and we might be able to save his life. In this case, however, there is no sick person present who could benefit from the procedure; rather the doctors want to understand the case for future reference. The rule then is that because of such remote concern we do not override any biblical prohibition, and not even a rabbinical prohibition. It is hard to make a distinction between a short-term and a long-term concern, and therefore we should not allow such a thing and there is no room for leniency.

I, the poor of mind, do not understand the Rabbi’s words. Has he not seen the Rashba’s Responsa which he himself quoted? He makes a distinction between embalming and autopsy saying: “there is no disgrace in embalming since it is done to honor the dead.” But this is a weak argument [lit.: passing breath] and the reader remains perplexed, not understanding how the holy rabbi considers the autopsy more disrespectful than embalming, as the embalming process requires the dissection of the body and removal of internal organs. Isn’t it a thousand times greater disrespect than the medical procedure which is limited, measured, and meant to remove the stones from the dead body?

If it is because he considers embalming a sign of honor to the dead, I find it hard to accept, because if we allow such great disrespect in order to cause fake honor to one man only, how will we not permit a minor disrespect for the honor and physical benefit of the general public?

Also, the Rashba permitted the procedure [of pouring lime on the body to hasten decomposition] not because it is honorable but because the dead flesh does not feel the pain of the scalpel, and he used the fact that Jacob was embalmed as a proof that the dead feels no pain or disgrace. It is clear from what the Rashba wrote that as long as there is no pain or disgrace, a procedure could be conducted, even if it adds no honor to the dead person. How then does Rabbi Landa reject the argument of Rashba without prooftext?

We also find that the authors of Tosafot wrote: “it is not common to dissect a dead body into small pieces and cremate it” – insinuating that dissecting and cremating is allowed, though uncommon, and their words are supported by the text of the Talmud. They also wrote in their explanation to the term burnt ash: “burnt ash is the ash remaining after burning bones” insinuating that there is no prohibition in cremating human bones.

Similarly, Rabbi Abraham Gombiner writes: (Magen Abraham, Orah Hayyim, 311:3) that the disrespect associated with cremation is forbidden only when it is done publicly, thus causing the observers a feeling of shame [the case discussed is saving a body from a burning house on Shabbat, and the ruling is that since the cremation happens away from the public eye, Shabbat should not be transgressed to save the body].

It is also clear from the above-mentioned case in Bava Batra 154:1 that plaintiffs can request exhumation and physical examination for monetary claims, even though the examination and the consequent disrespect will be observed by the living. The only reason the request was denied was that the posthumous examination would not have been reliable.

It is therefore very hard to accept the ruling of Rabbi Landa who took such unyielding position. We permit transgression of Shabbat, which is punishable by stoning, for a double doubt [referring to a case of a collapsed building where there is a doubt whether someone is in the building, and even if he is inside, whether he survived or not – hence a double doubt]. How much more so we should override the concern for disgrace, which is not a prohibition, in order to improve the world by enhancing medical science and benefiting tens of thousands of people in future generations.

I also do not understand why he wrote that it is hard to make a distinction between a short-term and a long-term concern. The reality is that all diseases and plagues are constantly present, and there is always a chance that a case similar to the one at hand will present itself to the doctor that very day, so why would we not try as much as possible to create preventive medicine? Also, regarding Shabbat, it is understandable that we should not transgress it for something which might happen much later [so the act could wait for the next day], so the concept of a long-term concern does not apply to Shabbat [היכא דלא אפשר לא אפשר]. In the case rabbi Landa dealt with, however, a need might arise today or tomorrow, and maybe even immediately, so why would we not override the concern of disgrace which is not at all forbidden?

His opinion is even more perplexing because he himself allowed the exhumation of a baby who was buried without circumcision in order to circumcise him at the gravesite (Noda BiYhuda, Vol.II, Yoreh De’ah 164), a procedure which has no source in the Talmud or the Midrash. It is only a custom mentioned by the Tur in the name of one of the Geonim (Yoreh De’ah 263), for the feeble reason of removing from the deceased the shame of not being circumcised by cutting the foreskin, which anyway would have been decomposed within a couple of days of the burial. Rabbi Landa allows causing a disgrace to the body for the personal gain of the deceased alone, yet he forbids the performance of a procedure which can affect the lives of many for generations to come – this is indeed perplexing.

In conclusion, the ruling of rabbi Landa are not halakhically binding and the main opinion to follow is that of the Rashba and the other authorities I mentioned, which is that there is no pain, disgrace, or prohibition in performing autopsies, even when it is not for the sake of the living, and if it is for the well-being of the living, there is no doubt that all of them will thank and bless and praise those who hurry to take care of the issue.

But behold, I have encountered an ostensibly terrifying text, that of Rabbi Moshe Sopher (Hatam Sopher, Yoreh De’ah 336) who wrote that a man who sold his body to science is as good as one who was not born at all, since he does not care for his own honor, let alone the honor of his Maker. His words are destructive. Why would he launch a war against a poor, desolate man who took money, whether a great or meager sum, to provide for himself and his family or to bequeath his poor children. By doing so, that man benefits the public and enables the saving of thousands of people, since he supports the development of medical science and understanding. Not only has that, but the increase of scientific knowledge aggrandized God’s name, since He is known through His actions. How can we cover the truth with a clay vessel and write vile words [wordplay in Hebrew – פסכתר\פלסתר] against that man, saying that he did not care for the honor of his Maker? This is also perplexing.

The extrapolation of rabbi Sopher, saying that the man did not care for his own honor, let alone that of his Maker, does not have any foundation. That man has sold an object which would have perished after his death; hence the sale produces no pain or disgrace. There is no source to forbid such an act, not in the Yerushalmi or Babylonian Talmud, not in the Midrash, and not in the writings of the great Halakhic authorities of all generations. On what did Rabbi Sopher base his argument, as we see there is not even the weakest text proof to lean on?

However, after asking people who were aware of the case [Rabbi Messas probably asked one of his correspondents in Europe to investigate the matter] it is obvious that when the author spoke of one who sells his body to the doctors, he referred to the medical academy in which hundreds of students learn medicine and surgery. In that school they all stand together during the autopsy in which the body is dissected to all organs and veins. Each organ and vein is observed and discusses, and then one group leaves and another group comes in. All that while the dissected body remains on the instructors’ table for a day or two, or even more, and after that the remains are cremated or used elsewhere. The prohibition of rabbi Sopher refers to this scenario, but if two or three doctors will deal with the body in order to understand a certain disease, or if they dissect one or two organs, he will also admit that not only it is not forbidden but it is a Mitzvah performed by that man’s body [wordplay on the difference between מצוה בגופו\מצוה בממונו], as he is extending his generosity to all people in all generations by helping them expand their medical knowledge, even if it by one detail only. This, in my opinion, is how we should understand the words of Rabbi Sopher.

Despite all that, even regarding the procedure he discussed, there are those who say it is permissible, as I have found in the periodical Yagdil Torah (Vol. 5:15) and an accompanying booklet, which I have borrowed and had now for a while. I am presenting the text here verbatim [אב”א תב”ת: אות באות, תיבה בתיבה]:

Regarding a person who bequeathed his body to science and the enhancement of medical knowledge there are different opinions. According to Rabbi Eliezer Pearl it would be forbidden, and according to Rabbi Yehudah Leib Levin it would be permissible with the agreement of the person, in order to not bring medical progress to a halt. Rabbi Levin forbids, however, a Cohen from performing an autopsy because of impurity. Rabbi Bernard Revel opposes him and holds that a Cohen can perform autopsies of non-Jews since there is a double doubt here: if we follow the opinion of Rabbi Abraham Bar David [Ra’avad], then the priestly code of impurity does not apply today, and if we follow the opinion of Maimonides, the laws of impurity do not apply to a body of a non-Jew. Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Henry Illowy is of the opinion that it is permissible even for a Cohen to perform autopsies of Jews since it is direly needed for the public’s benefit and there is no other way to guarantee the progress of medical science. He brings further support for his opinion from the fact that the Torah allowed even the High Priest to become impure in order to take care of the burial of a Met Mitzvah [one who had no relatives, or a body found in the open], because letting the body remain unburied could be dangerous for the public. The Torah also allowed the priest to deal with lepers and plagues of houses and objects which cause impurity in order to removed obstacles from the public’s path, and regarding life-threatening situations it is said that the one who acts without delay is praiseworthy. [The enhancement of medical knowledge] is as if the patients are present here, in which case Rabbi Landa will agree that a procedure is permitted in order to cure them. However, our opinion, based on honest analysis [לדעתנו ולדעת האמת – not clear if it is the opinion of R. Illowy or of the editor], even if the patients are not present here they are considered as present, and there is no disrespect for the dead in performing the procedure, since the surgeons have no intention to show disrespect to the dead, rather only to benefit other, and they do their work with a sense of responsibility. Regarding the impurity of a Cohen, we only keep its laws today so they would not be forgotten, but they are not really binding since all of us have contracted impurity at one point and since we have no evidence that the Cohen’s genealogy is uninterrupted [therefore there is a doubt whether he is a Cohen]. It is recommended to act leniently where there is such great need to protect the health of the public and to save lives. This ruling has been approved by several rabbis and has been acted upon daily, by many respectable people who bequeathed their bodies to science. Many benefits resulted from their generosity, and their acts of charity will live forever – the body perishes but their loving-kindness is everlasting, and they will have a great reward in the spiritual world.

This is the article, verbatim, and it proves that this was not a theoretical discussion but rather a practical one, and that people were not concerned about the opinion of those opposed but rather did and succeeded [in bequeathing their body to science].

Now all this discussion is regarding autopsies, but in our case it is obvious to the scholar and the disciple alike, that the transplant is permitted, since there is no dissection of an organ and no disrespect, because this is how the procedure is performed: the surgeon makes a small slit on the side of the eye of the deceased, and removes with small pincers a small piece from the third or fourth layers of tissue, being that the eye comprises seven layers of tissue and liquid between them. The part removed weigh less than 0.25 of a gram, and it is placed immediately in a dish with alcohol. The eye of the deceased, meanwhile, closes back as it was before. When the surgeon is about to operate on the blind person, he makes a small slit in his eye and inserts the tissue removed from the dead body. He then bandages the eye for a certain period to let the transplant merge into the eye of the living person, eventually restoring his eyesight. This is the description of that amazing wisdom. Blessed be He who granted His wisdom to mere mortals and Blessed be He who opens the eyes of the blind. Who then will dare to obfuscate wisdom with senseless words to deny us such great blessing [based on the verse in Job 38:2 – מי זה מחשיך עצה במלין בלי דעת].

2. Deriving benefit from the dead. It is well known that the dead flesh does not cause impurity when it is less than a KeZayit (28 grams), as Maimonides writes in the laws of the Impurity of the Dead (chapters 2-3). And if it is less than that weight it will not cause impurity unless it is a whole organ, with bones, flesh and sinews (ibid.). Now, whatever does not cause impurity does not fall under the category of the flesh of the deceased which one cannot derive benefit from, and so wrote rabbi Mordechai Yafeh in his Responsa (49) that the measurement for determining the prohibition of deriving benefit is KeZayit. It is therefore obvious that in our case there will be no problem since we deal with the removal of a very small part.

3. Lack of proper burial: this is also obvious that there is no concern regarding that which you are allowed to derive benefit from, due to its small measurements, and even more so with the part of the cornea which is negligible.

This is what seems to me obvious regarding your question.

Yossef Messas

Meknes, Adar I, 1951 [the rabbi used the Hebrew words אשית בישע – I shall send redemption, to allude to the date as well as to the importance of the matter at hand]

Ref:

1 Mayim Qedoshim, 109.

2 There are rare cases of a living donation of one cornea, limited to healthy corneas from an enucleated eye.

3 www.Hods.Org , the website of the Halakhic Society of Organ Donation, provides extensive Halakhic discussions

on all issues related to organ transplants.

4 Tosfot Yom Tov, M. Avot 2:7.

5 On Berachot 18:2, in the name of Sepher Hassidim.

6 Job 14:22.

7 Eccl. 12:7.

8 Gen. 3:19.

9 Tractate Sotah, 34:2. Note that Rabbi Messas refers to the text as Midrash, even though it appears in the Talmud.

10 Berachot 18:2.

11 Sanhedrin 46:2.

12 Arba’a Turim, Yoreh De’ah, 345.

13 Laws of Mourners 12:1; laws of Acquiring and Gifts 11:24. No distinction is made between having or not having

relatives.

14 Bet Yossef, 348:3.

15 Prov. 21:3, and Rashi on Deut. 24:19.

16 Kelim, 12:7.

17 Rabbi Messas is saying that we have abandoned the Mishnaic law, which forbids using the services of a non-

Jewish doctor or barber, because we no longer fear that they will cause the patient or client any damage.

18 Teshuvot HaRashba, 1:816. The question dealt with a man who wished to be buried at his family’s gravesite but

because of an emergency was given a temporal burial in a far place. His children asked if they can pour lime on the

exhumed body, in order to consume the flesh and to be able to transport it.

19 Which was applied to Jacob by the Egyptians. See Genesis 50:2.

20 Noda BiYehuda, Vol.II, Yoreh De’ah 210.

21 Bava Batra, 154:1.

22 Meaning that it is hard to determine whether the need for the knowledge culled from the procedure will arise in a

short while or in the far future.

23 Lit.: imagined honor, meaning that it is only the socio-cultural norm which render acts such as embalming

honorable.

24 Hullin,125:2.

25 wrote in tractate Taanit (16:1)