Introduction to Kahal Kadosh Mikveh Israel (Congregation Mikveh Israel)

Kahal Kadosh Mikveh Israel, also known as Congregation Mikveh Israel, is one of the oldest Sephardic synagogue in the United States. It stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of Sephardic Jews in America. Established in Philadelphia in 1740, it represents a rich tapestry of Jewish history, culture, and community, thriving long before the formation of the United States. This article highlights the remarkable journey of the congregation, its pivotal role in the early Jewish community, and our recent visit where we learned about its historical significance from Rabbi Yosef Zarnighian and Rabbi Emeritus Albert E. Gabbai. Their insights illuminated the congregation’s profound impact on both the local community and the broader Jewish narrative.

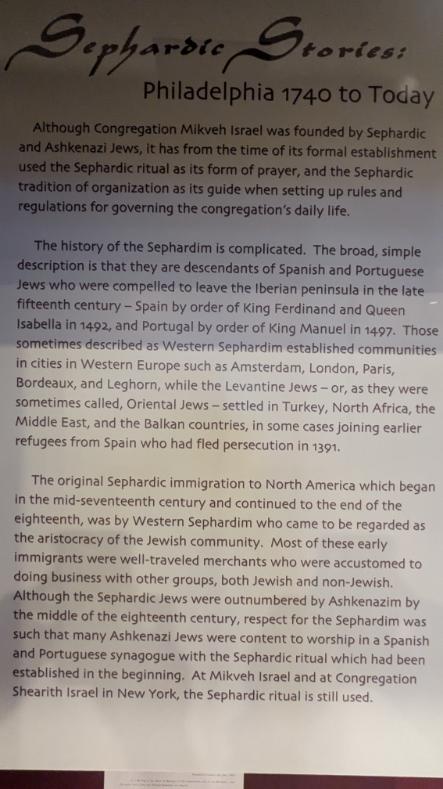

A Glorious Beginning: The Early Years (1740–1782)

Congregation Mikveh Israel traces its roots to September 25, 1740, when the Province of Pennsylvania granted permission for a burial ground that would serve the Jewish community. The cemetery, located at the corner of Spruce and South Darien Streets, was one of the first dedicated spaces for Jewish interment in America and symbolizes the establishment of a Jewish presence in the New World.

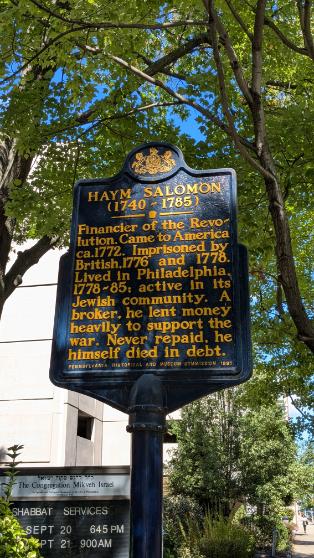

By the 1760s, as the Jewish population grew due to immigration from Western Europe and the Caribbean, the community organized itself for religious services. The acquisition of the first Torah scroll in 1761 marked a significant milestone, allowing for formal services to be held in private homes. The formal charter, established in 1773, reflected the community’s dedication to creating a permanent Jewish institution, and it included influential members who were deeply involved in the Revolutionary War. Figures like Haym Solomon, a financier, and Jonas Phillips, an active revolutionary, showcased the congregation’s integral role in American history.

A New Home: The First Synagogue (1782–1825)

In 1782, Mikveh Israel constructed its first dedicated synagogue at Third and Cherry Streets, designed to accommodate a growing congregation. The building featured elements that were not only functional but also symbolically significant. The use of traditional Sephardic architecture and decorative motifs echoed the congregation’s roots, fostering a sense of identity among its members.

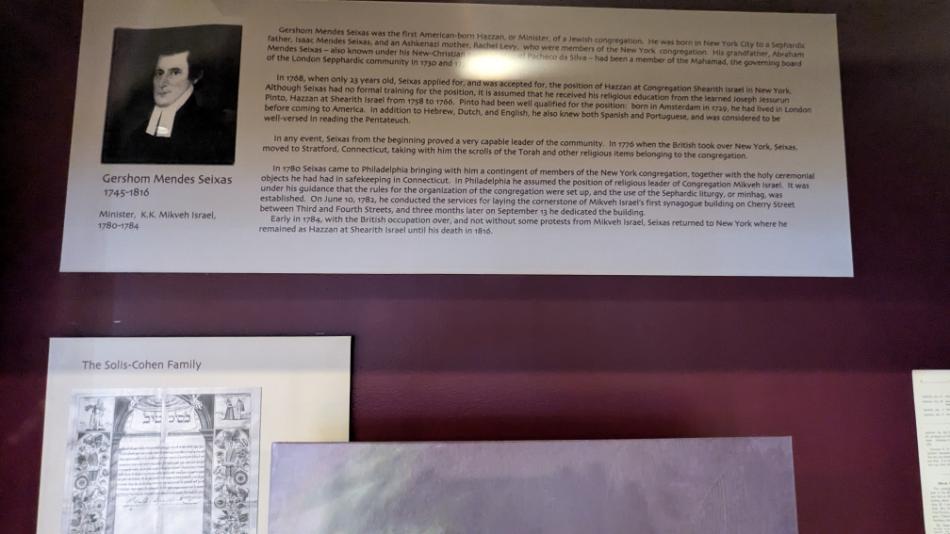

During the dedication ceremony, Rabbi Gershom Mendes Seixas, a prominent leader, invoked blessings upon George Washington and members of Congress, underscoring the congregation’s commitment to American ideals and its connection to the founding fathers. This event illustrated the synagogue’s role as a gathering place for Jewish and non-Jewish leaders alike, reflecting the community’s influence in the broader social and political landscape of the time.

Evolving Through Time: The Second Building (1825–1860)

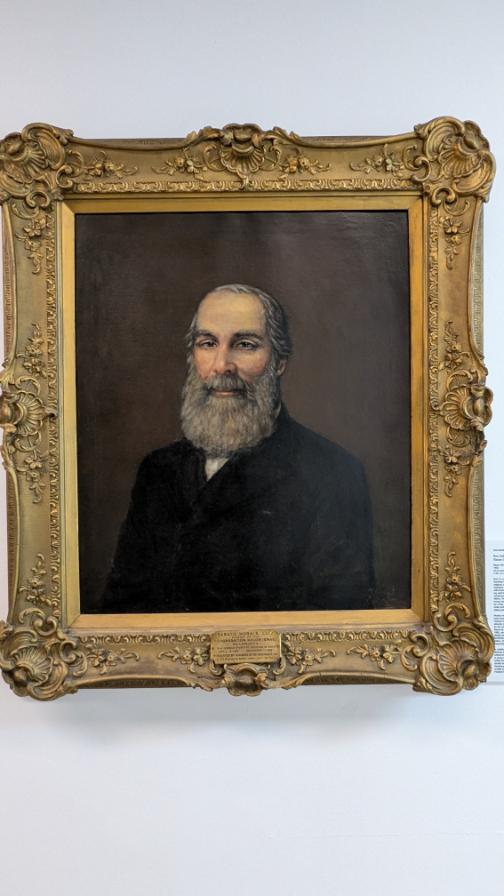

The congregation’s second synagogue, completed in 1825, was designed in the Egyptian Revival style, a trend that symbolized both cultural sophistication and a connection to ancient Jewish history. Under the leadership of Isaac Leeser, a passionate advocate for Orthodox Judaism, Mikveh Israel became a stronghold of traditional practice.

Leeser’s tenure was marked by a commitment to Jewish education and community engagement. He established the first Hebrew school in Philadelphia, providing a foundation for Jewish learning that influenced generations. Additionally, his writings and sermons addressed contemporary issues facing the Jewish community, reinforcing the importance of tradition amidst a changing world.

The 20th Century: A New Era (1909–1976)

In 1909, the synagogue moved to a new location at 2321 N Broad Street, which allowed for a larger and more accommodating space for the community. This new chapter coincided with a period of significant social change, as the Jewish population in North Philadelphia flourished. The congregation took an active role in addressing social issues, such as advocating for Jewish education, supporting Union soldiers during the Civil War, and participating in various civic initiatives.

After World War II, however, the demographic landscape began to shift, leading to a decline in the Jewish population in North Philadelphia. In response, Mikveh Israel relocated again in 1976 to its current home at 44 North Fourth Street, nestled within Philadelphia’s Old City Historic District. This move not only revitalized the congregation but also positioned it among the historic landmarks of the city, allowing it to attract visitors and new members interested in its rich heritage.

A Warm Welcome: Our Visit

During our recent visit to Congregation Mikveh Israel, we were warmly welcomed by both Rabbi Yosef Zarnighian and Rabbi Emeritus Albert E. Gabbai. Their passion for the congregation’s history and commitment to preserving Sephardic traditions was evident as they shared stories of its founding and evolution.

As we toured the sanctuary, Rabbi Gabbai explained that the layout reflects traditional Sephardi customs, with the teva set back toward the rear, facing the ark. On either side of the teva, rows of seating for men are arranged, while behind these sections are elevated seating areas for women, providing better viewing during services. Rabbi Gabbai emphasized that Sephardim historically never used a mechitza to “separate women,” a practice he noted was a more recent development among Ashkenazim. He added that the shift away from balconies for women’s seating was primarily due to the increased costs of construction. Instead, the elevated seating accommodates the need for visibility without segregation.

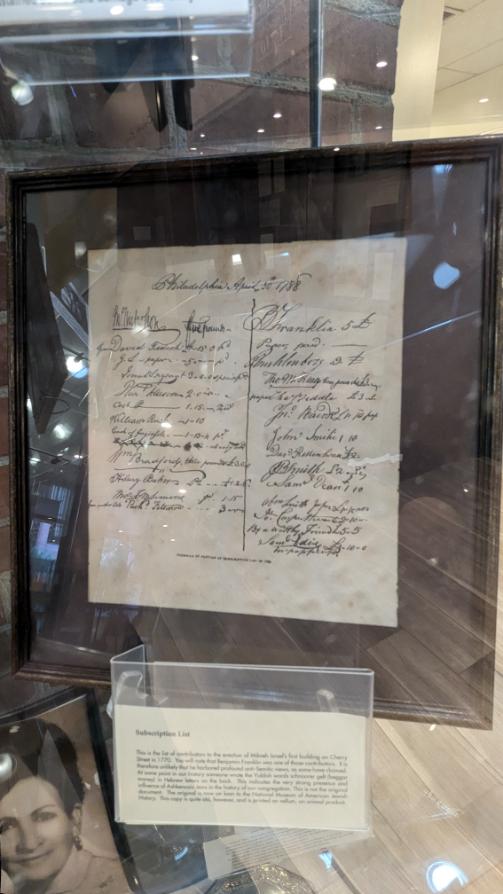

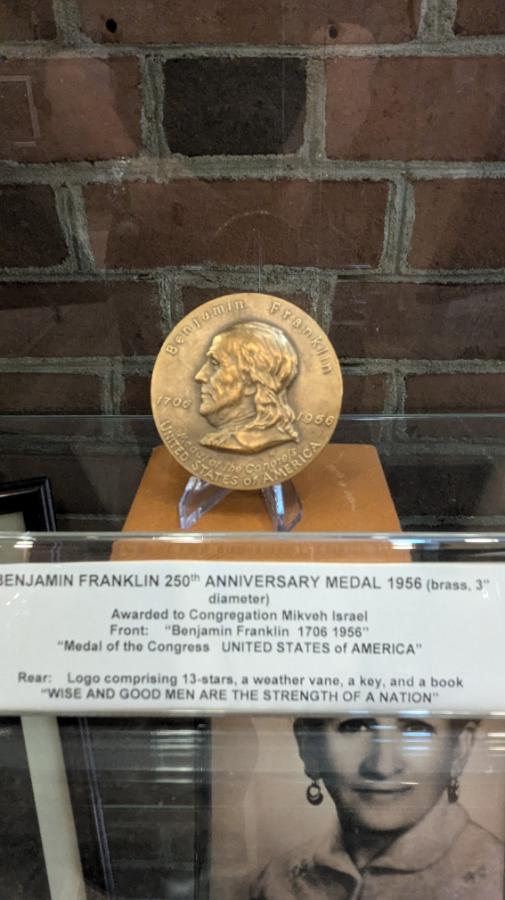

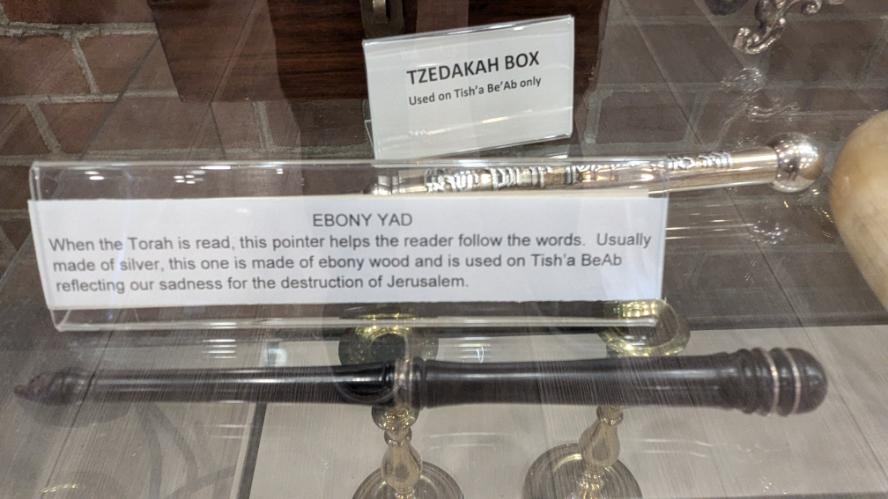

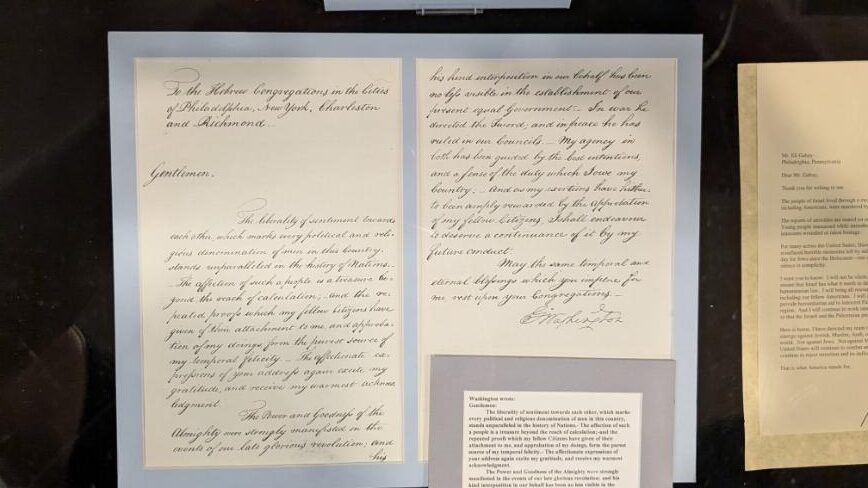

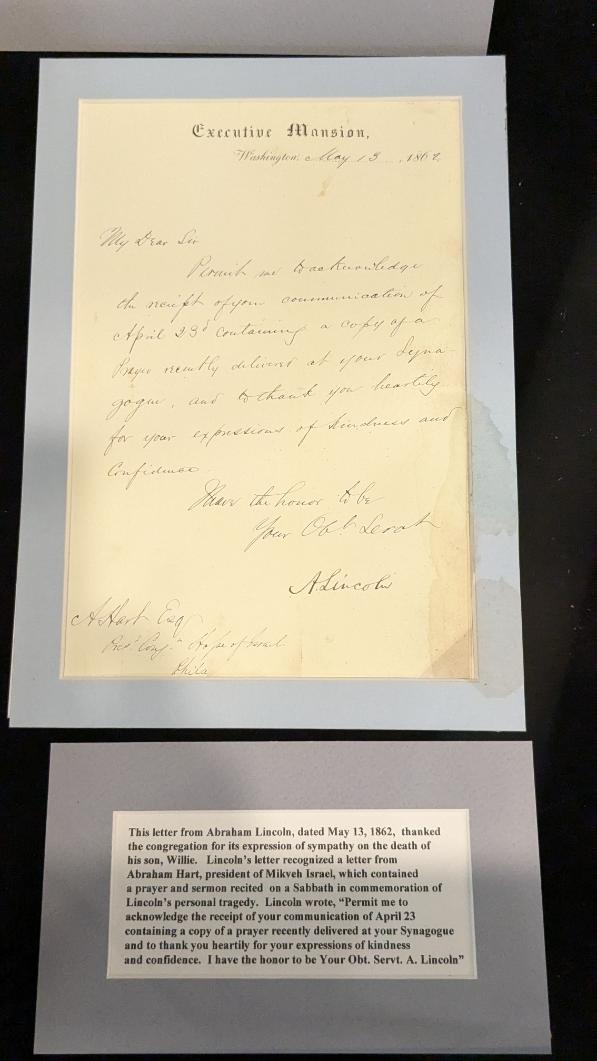

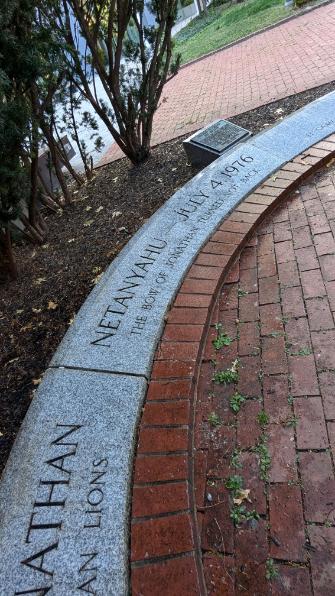

The tour included highlights of significant artifacts: a plaque detailing the synagogue’s history, a letter from George Washington expressing his support for the Jewish community, Benjamin Franklin’s signature on a donation document, and a memorial for Haym Solomon. We learned about the synagogue’s unique features, such as the marble teva, the original table where the Torah sits, and the distinct ebony wood “yad” used exclusively for Tisha B’Av readings. These artifacts not only enhance our understanding of the congregation’s heritage but also serve as a reminder of the deep roots and traditions that have shaped its identity.

Celebrating Sephardic Traditions

Mikveh Israel is not just a place of worship; it is a vibrant community hub that actively promotes Sephardic culture. The congregation hosts various cultural programming and educational opportunities, including lectures, workshops, and holiday celebrations that reflect the diversity of Jewish traditions.

The kitchen is kosher, supervised by the Community Kashrus of Greater Philadelphia, ensuring adherence to dietary laws while also providing meals during community events. The congregation’s involvement in community outreach initiatives further highlights its commitment to the values of spiritual care for all, encouraging members to engage with the broader community.

Rabbi Zarnighian and Rabbi Gabbai continue to foster a welcoming environment where members of all ages can connect with their heritage. Their leadership promotes intergenerational dialogue and encourages the younger members to embrace their Jewish identity in a rapidly changing world.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Congregation Mikveh Israel stands as a beacon of rich Sephardic traditions and heritage, rooted in the customs of the Spanish and Portuguese communities. The synagogue follows the liturgical practices of the Amsterdam esnoga, which emphasizes a unique blend of prayer and song, often characterized by melodic chanting and rich vocal harmonies. This tradition is evident in their services, where the congregation engages in traditional Sephardic melodies that reflect their historical roots.

Moreover, the synagogue upholds significant customs such as the celebration of Sukkot with community gatherings and the reading of the Torah during special occasions, honoring both the written and oral traditions that have been passed down through generations. Events such as Sheva Berachot and Bar/Bat Mitzvah celebrations are infused with Sephardic customs, including the recitation of blessings that highlight the importance of family and community.

Additionally, the architectural design of the sanctuary exemplifies Sephardic principles, with its teva set back to the rear, reflecting a communal approach to worship. This layout promotes inclusivity and engagement, allowing both men and women to participate actively in the spiritual life of the synagogue.

By preserving these traditions and integrating them into contemporary worship, Congregation Mikveh Israel not only honors its past but also enriches the Jewish community in Philadelphia today.

Visiting Mikveh Israel

Congregation Mikveh Israel is conveniently located in Philadelphia’s historic district, making it an ideal stop for visitors exploring the area. The synagogue is just a short walk from notable landmarks such as:

- The Liberty Bell: A symbol of American independence and a must-see for history enthusiasts.

- Independence Hall: The birthplace of the United States, where the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were debated and adopted.

- Betsy Ross House: The home of the seamstress who is believed to have made the first American flag.

- National Museum of American Jewish History: A comprehensive exploration of Jewish life in America from its inception to the present day.

- Franklin Square: A historic park with family-friendly attractions and a beautiful view of the city.

Contact Information

For more information about Congregation Mikveh Israel, including service times, educational programs, and community events, you can reach them at:

- Address: 44 North Fourth Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106

- Phone: (215) 922-5446

- Email: info@mikvehisrael.org

- Website: mikvehisrael.org

Ohr HaChaim Yomi – Shemini