Introduction

During our captivating road trip tour of old Sephardic Synagogues in the Southeast, the iconic Congregation Mickve Israel Synagogue in Savannah, Georgia, stood out as a significant stop. Located at 20 East Gordon Street, Savannah, GA, this architectural gem, deeply rooted in Sephardic heritage, offered us a profound glimpse into the rich history of the Jewish community in the region. As we explored its hallowed halls and admired its exquisite details, we couldn’t help but appreciate the synagogue’s enduring legacy and its pivotal role in preserving the Sephardic traditions that have shaped the Jewish experience in the United States. Congregation Mickve Israel Synagogue truly embodied the spirit of Sephardic U, allowing us to connect with our ancestral roots and immerse ourselves in the vibrant tapestry of Sephardic history. To learn more about Congregation Mickve Israel Synagogue, visit their website at www.mickveisrael.org.

About Congregation Mickve Israel Synagogue

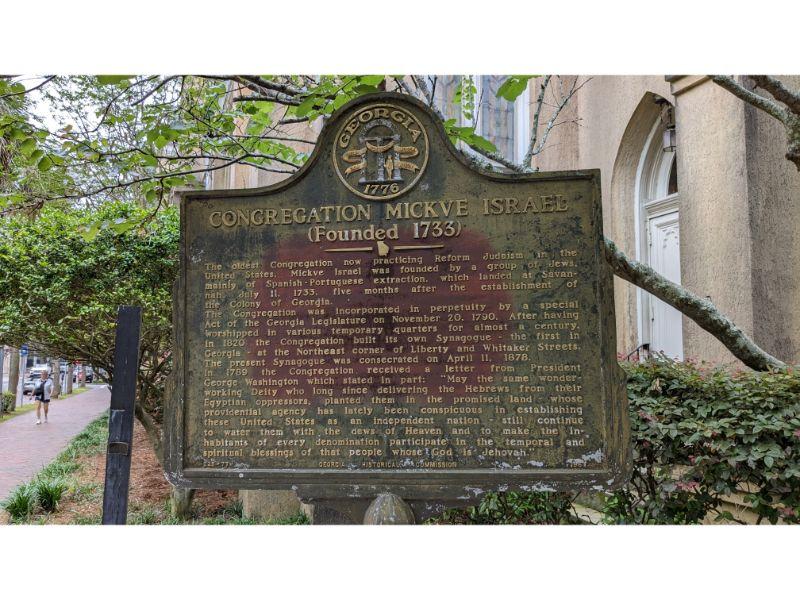

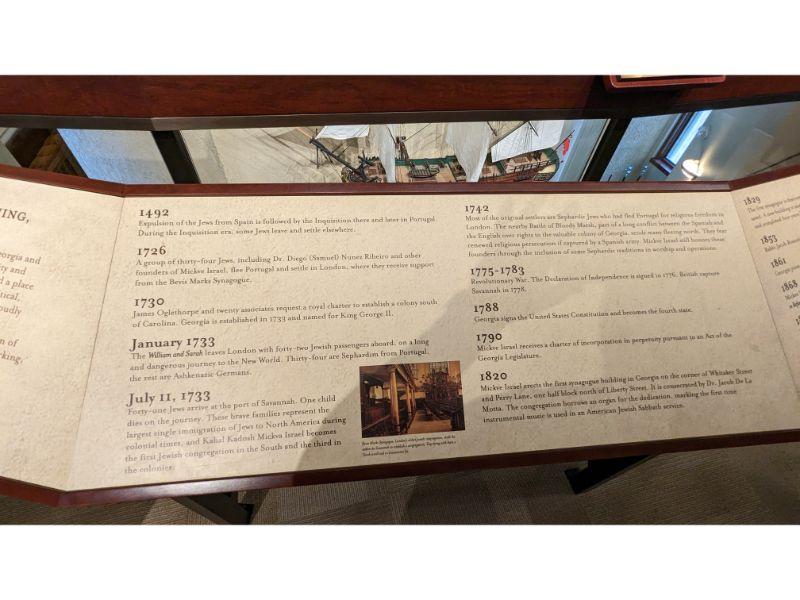

Congregation Mickve Israel Synagogue stands as a testament to the rich history and cultural heritage of Savannah, Georgia. Established in 1733, it is one of the oldest Jewish congregations in the United States, carrying immense historical significance. We explore the origins, milestones, and enduring impact of Congregation Mickve Israel, with a focus on its Sephardic roots, highlighting its profound influence on the local Jewish community and Savannah as a whole.

Origins of Congregation Mickve Israel

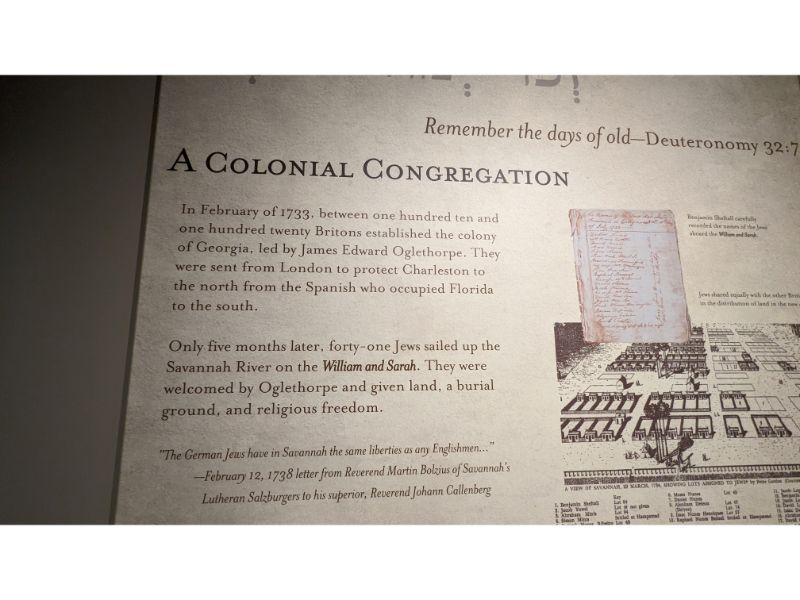

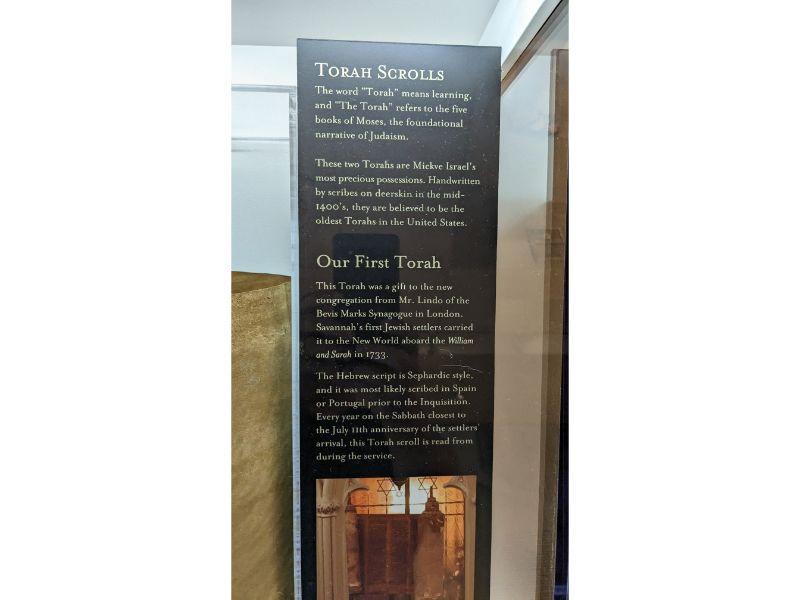

The establishment of Congregation Mickve Israel took place during a period of Jewish immigration to Savannah. Sephardic Jews, descendants of those expelled from Spain and Portugal during the Spanish Inquisition, played a crucial role in shaping the congregation. Seeking religious freedom and economic opportunities, these early Jewish settlers laid the foundation for a thriving Jewish community in Savannah.

Georgia On My Mind

The founding of Congregation Mickve Israel in Savannah, Georgia, can be traced back to the Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Spain and Portugal during the Spanish Inquisition. Many of these exiled Jews sought refuge in England, where they established a vibrant Sephardic community centered around Bevis Marks Synagogue in London.

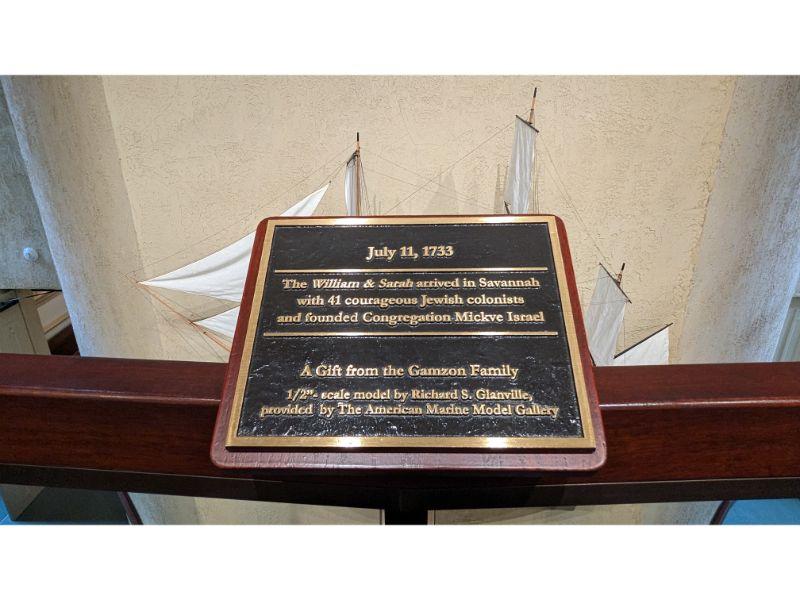

Dr. Samuel Nunes, a prominent member of Bevis Marks Synagogue, played a pivotal role in the migration of Sephardic Jews to Savannah. Recognizing the opportunity for religious freedom and economic prosperity in the newly established colony of Georgia, Dr. Nunes was instrumental in extending an invitation to the early Jewish settlers to join the journey on the ship “William and Sarah.”

In 1733, a group of approximately 40 Jewish passengers, led by Dr. Nunes, set sail from London to Savannah aboard the “William and Sarah.” This diverse group of settlers included Sephardic Jews who had found a temporary home in England after their expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula.

The arrival of these Sephardic Jews in Savannah marked the establishment of Congregation Mickve Israel. Dr. Nunes, serving as the spiritual leader, guided the congregation and ensured the preservation of Sephardic traditions, rituals, and customs.

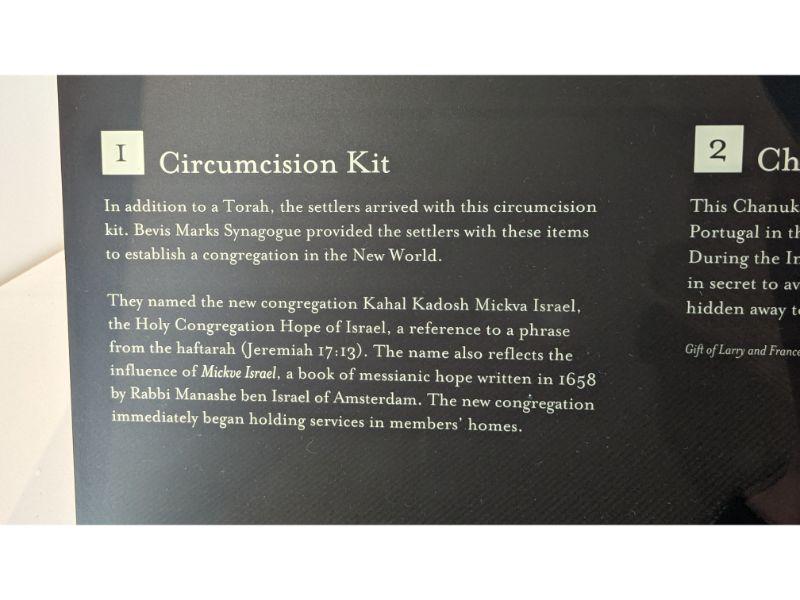

Congregation Mickve Israel and Bevis Marks Synagogue

The connection between Congregation Mickve Israel and Bevis Marks Synagogue remained strong throughout the years. The founders of Congregation Mickve Israel maintained close ties with their brethren in London, exchanging letters, seeking religious guidance, and sharing news of their progress in the New World. This connection to Bevis Marks Synagogue served as a reminder of their shared heritage and the enduring bonds of the Sephardic community.

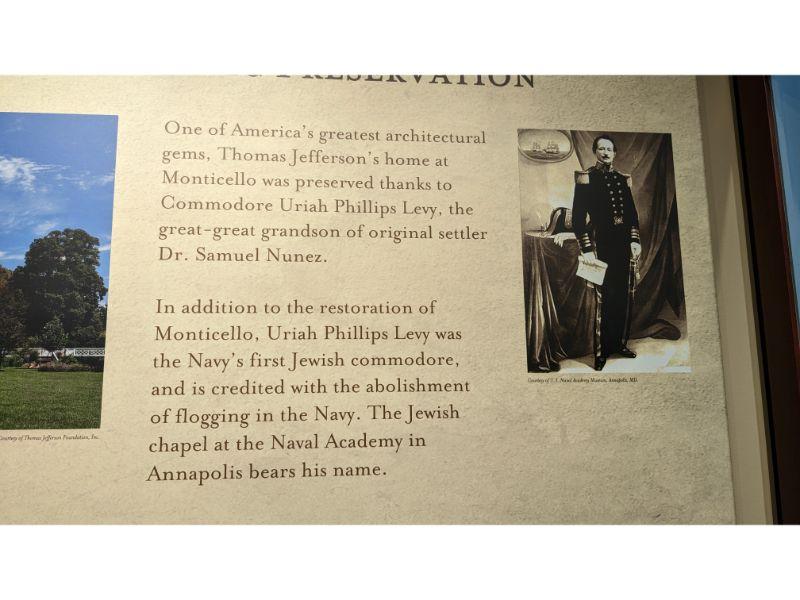

Dr. Samuel Nunes, with his instrumental role in inviting the early settlers aboard the “William and Sarah,” played a vital part in shaping the destiny of Congregation Mickve Israel. His leadership and dedication ensured the survival and growth of the congregation, firmly establishing its Sephardic roots in Savannah.

The journey of the original founders, their connection to Bevis Marks Synagogue, and Dr. Nunes’ pivotal involvement showcase the remarkable resilience and determination of Sephardic Jews to establish a thriving community in the face of adversity. Congregation Mickve Israel stands today as a testament to their enduring legacy and the enduring Sephardic influence in Savannah, Georgia.

Early Years and Growth

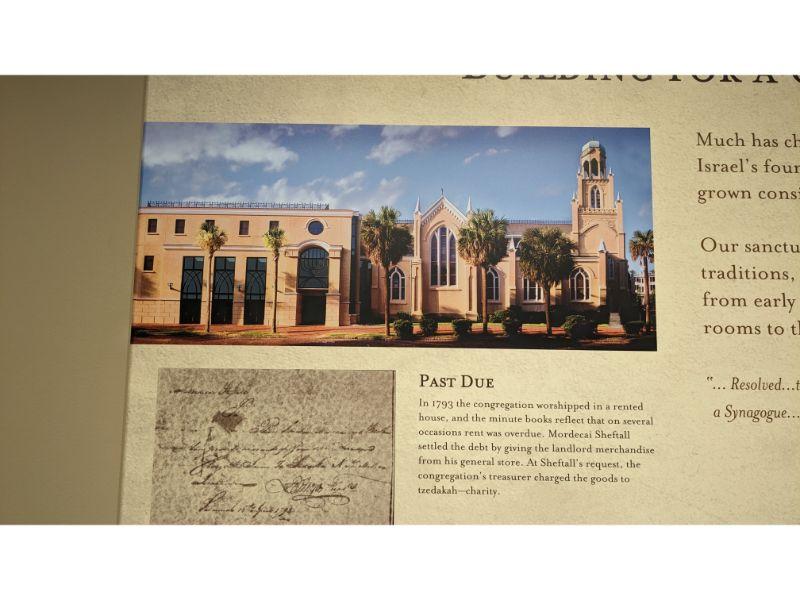

During its early years, Congregation Mickve Israel experienced significant growth and development. The congregation constructed its first synagogue in 1735, establishing a permanent place of worship and marking an important milestone in Savannah’s Jewish history. The Sephardic influence remained strong, shaping the congregation’s religious observance and cultural traditions.

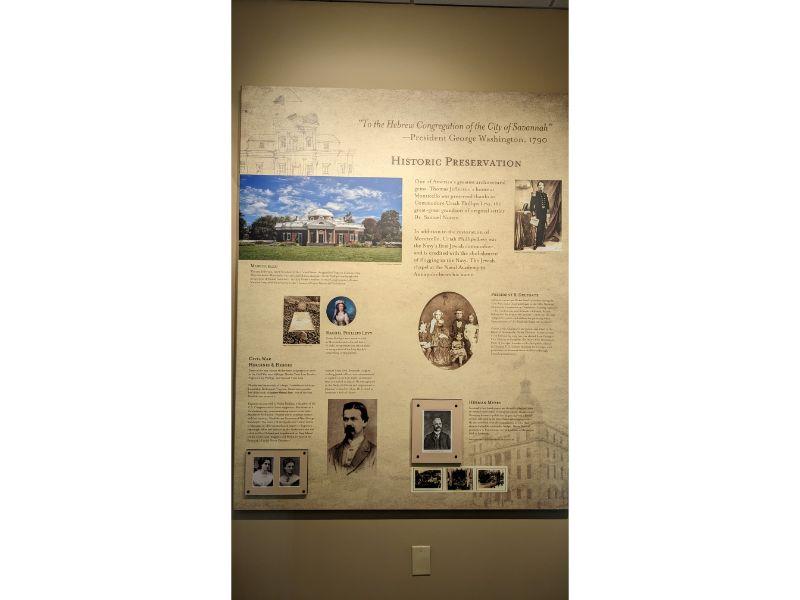

In the late 18th century, key Sephardic figures played a pivotal role in the congregation’s growth. Among them was Mordecai Sheftall, a prominent member who contributed to the thriving Jewish community in Savannah. Sheftall, a successful merchant and patriot during the American Revolution, exemplified the spirit of Congregation Mickve Israel by actively supporting both his faith and the cause of American independence.

Challenges and Resilience

The American Civil War presented significant challenges to Congregation Mickve Israel, as it did to many religious and cultural institutions of the time. Many members of the congregation faced losses and upheaval during this tumultuous period. However, the Sephardic community displayed remarkable resilience, maintaining their traditions and supporting one another throughout the war.

Despite the challenges, the congregation’s commitment to their faith and community allowed them to rebuild and thrive in the post-war years. The Sephardic Jews’ unwavering dedication ensured the continuation of Congregation Mickve Israel as a vibrant and influential institution in Savannah.

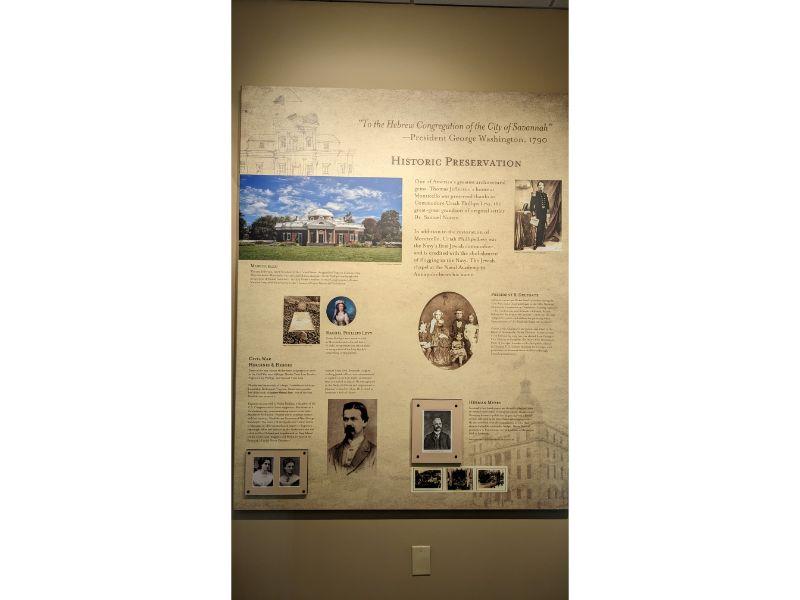

Preservation and Architectural Significance

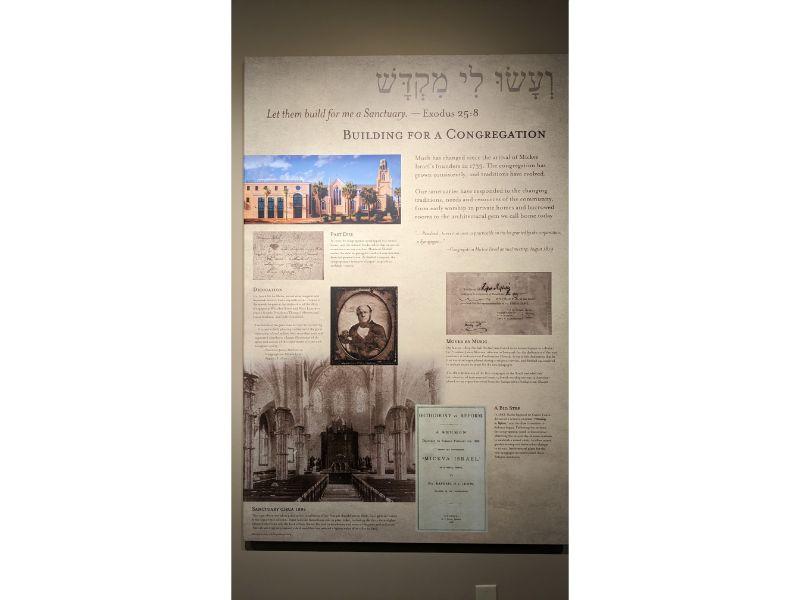

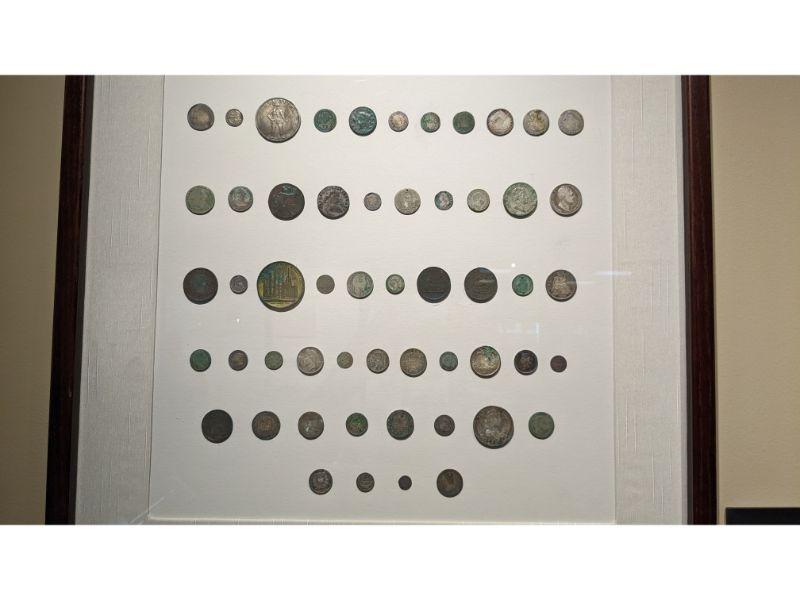

In 1876, Congregation Mickve Israel embarked on a significant renovation project that transformed the synagogue into its current architectural form. The redesign incorporated Gothic and Moorish elements, reflecting the eclectic tastes of the late 19th century. The preservation of the Sephardic heritage was evident in the architectural details, paying homage to the ancestral homelands of the congregation’s founding members.

The unique blend of architectural styles created a visually striking and culturally significant place of worship. The synagogue’s design stands as a testament to the congregation’s enduring connection to their Sephardic roots and their commitment to preserving their heritage.

The Tragic Fire and Restoration

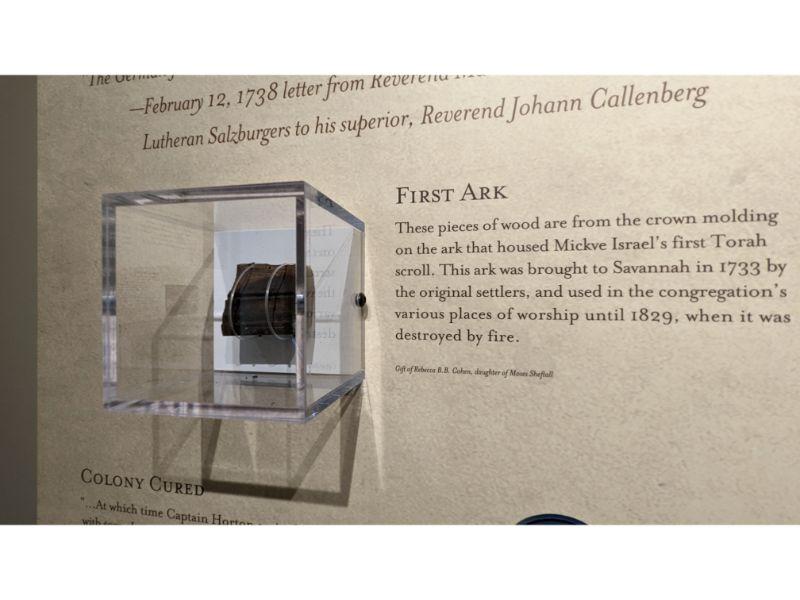

In 1820, a devastating fire destroyed the original synagogue building, causing a significant loss to Congregation Mickve Israel. However, the congregation’s determination and unity prevailed, and they quickly rallied together to rebuild. The reconstruction efforts resulted in the beautiful structure that stands today, a testament to the resilience and unwavering spirit of the Sephardic community.

The Organ and Stained Glass Windows

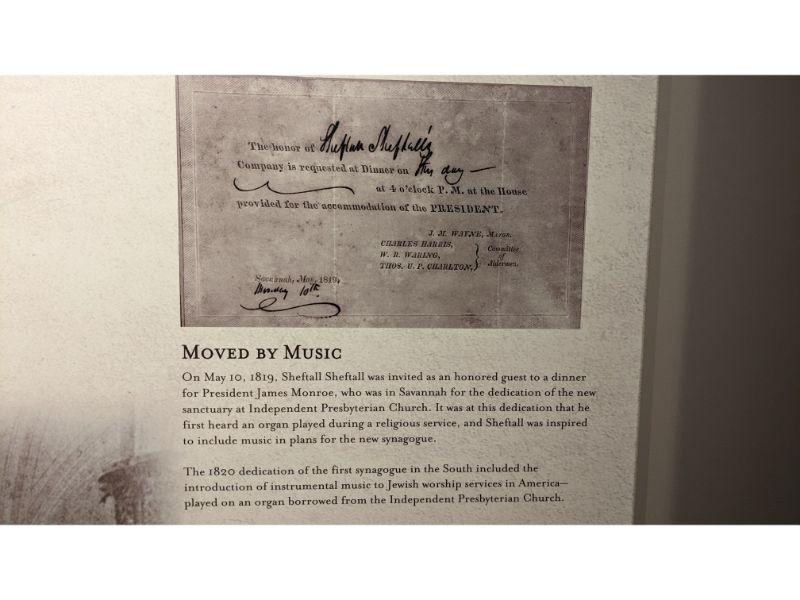

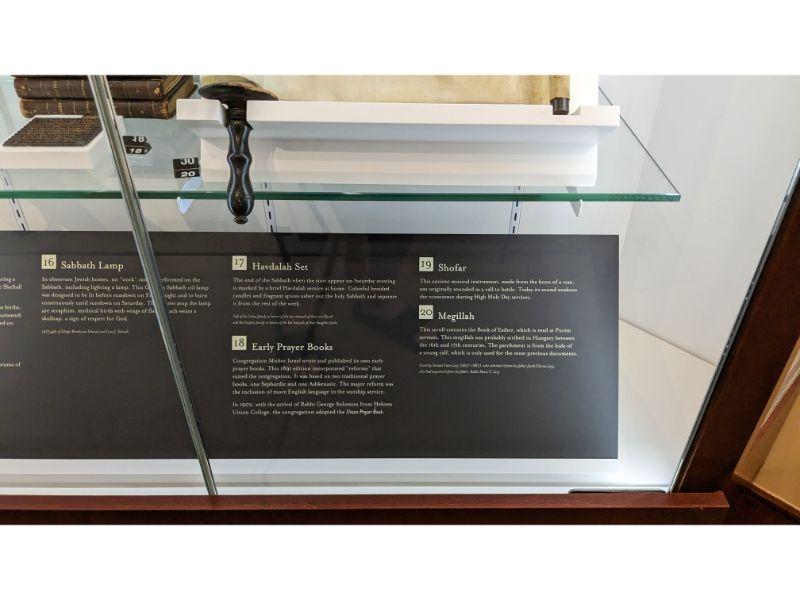

Within the newly rebuilt synagogue, additional elements were added to enhance the spiritual and aesthetic experience. In 1904, a magnificent organ was installed, adding a melodious and sacred dimension to the congregation’s worship services. The organ’s music filled the sanctuary, becoming an integral part of the congregation’s worship traditions.

The stained glass windows, installed during the renovations, depict biblical scenes and symbols significant to Jewish tradition. These exquisite windows not only contribute to the architectural beauty of the synagogue but also serve as visual representations of the congregation’s deep connection to their faith and heritage.

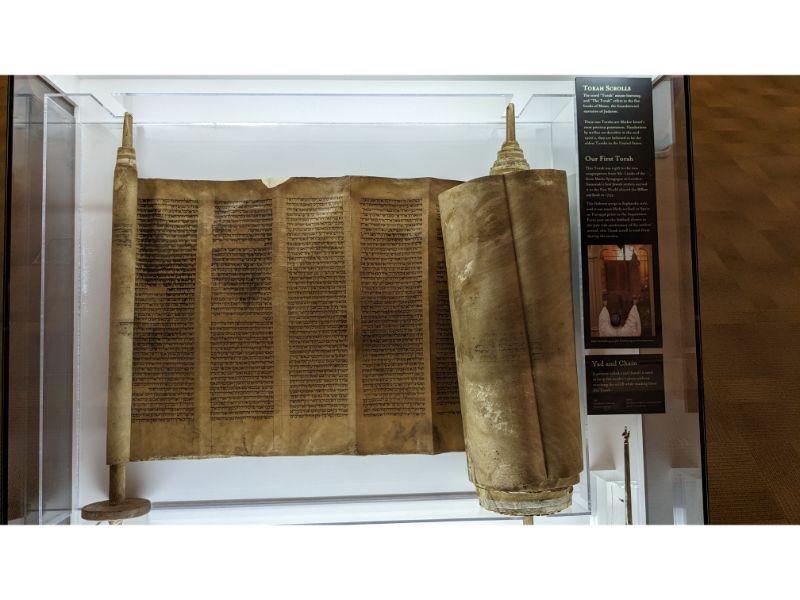

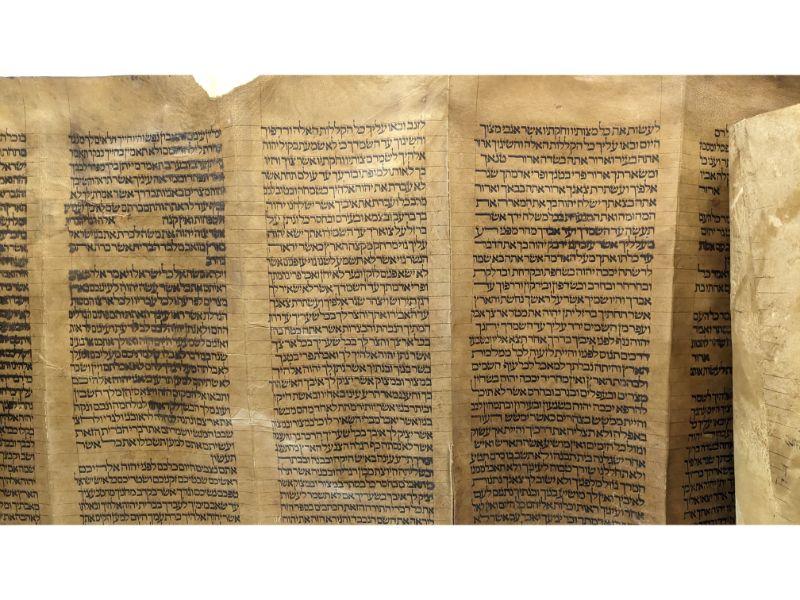

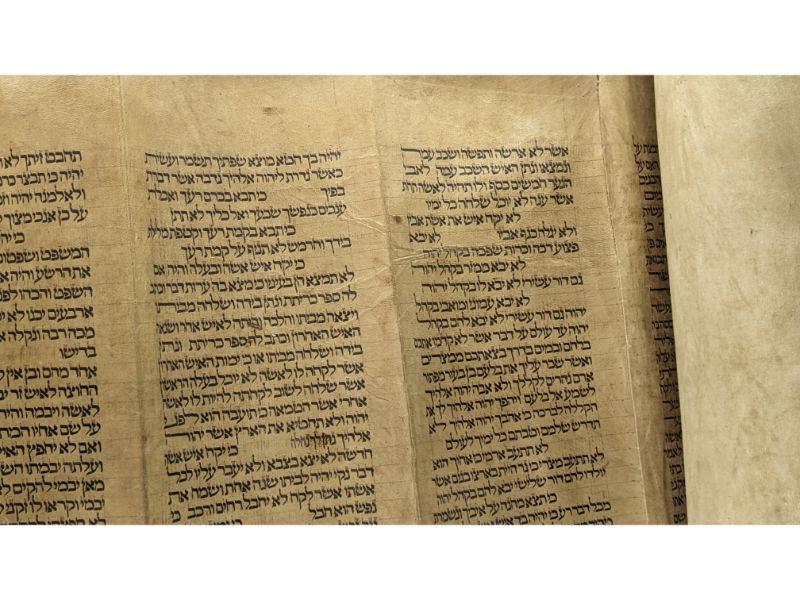

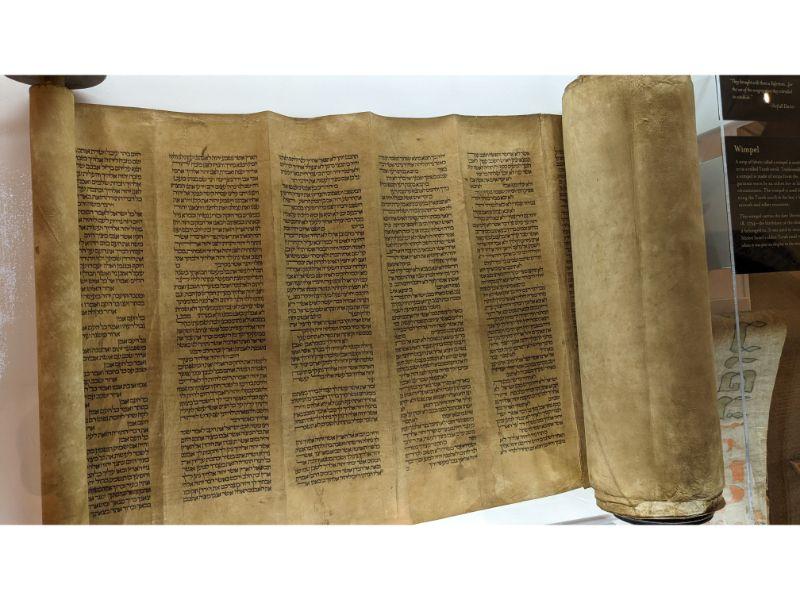

Sephardic Torah Scrolls and Museum

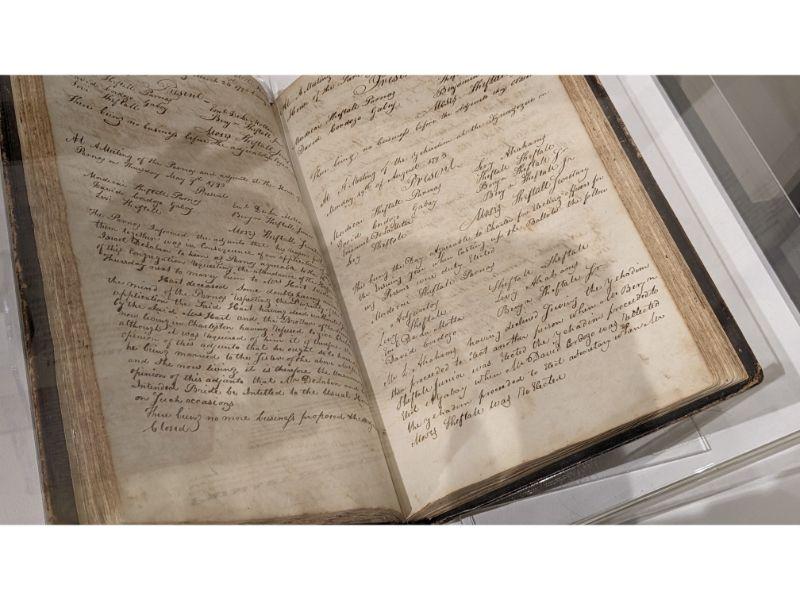

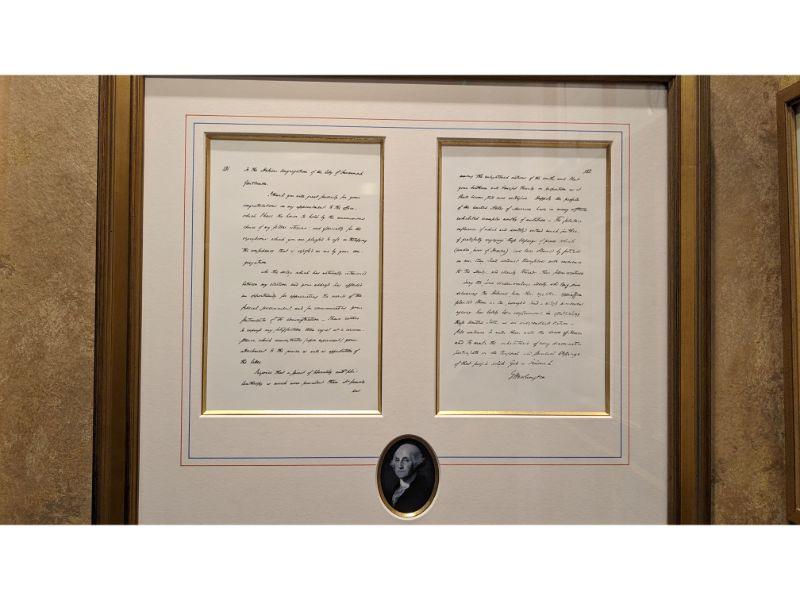

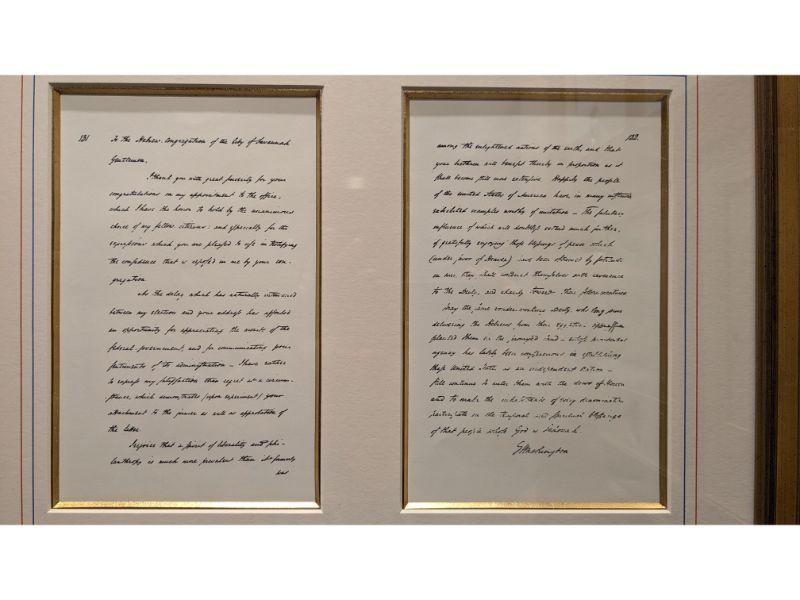

At the heart of Congregation Mickve Israel’s heritage are its two Sephardic Torah scrolls, which are housed and displayed in the synagogue’s museum. These meticulously handwritten scrolls on parchment are cherished artifacts that hold immense religious and historical significance. The Torah scrolls, adorned with beautiful covers and crowns, serve as tangible connections to the early Jewish settlers who established the congregation in Savannah centuries ago.

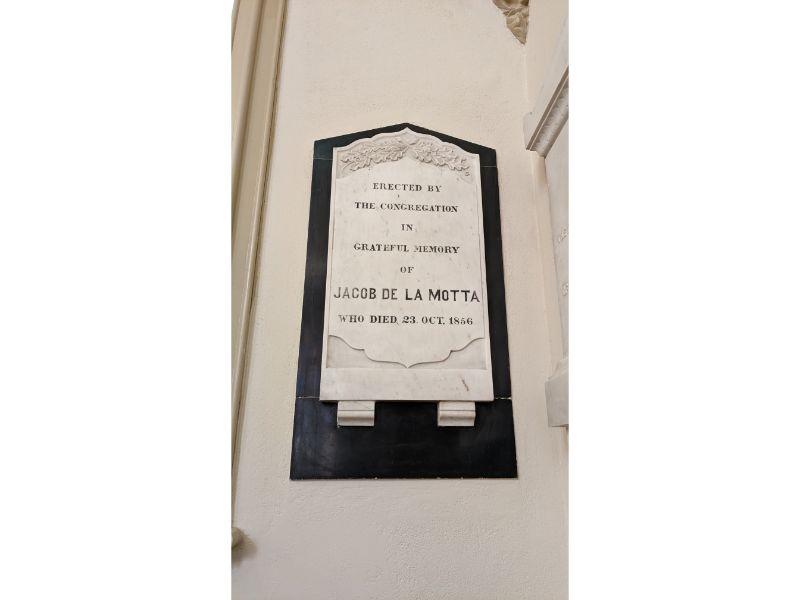

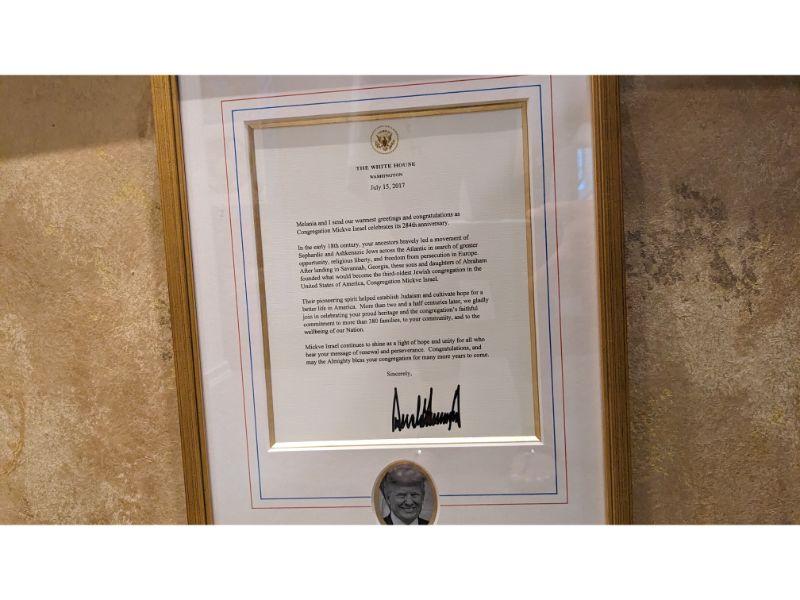

The museum, located upstairs from the main sanctuary, provides a captivating journey through the congregation’s history. Alongside the Torah scrolls, visitors can explore a remarkable collection of artifacts and documents that tell the story of Congregation Mickve Israel. The museum showcases historical photographs, letters, ritual objects, and archival materials, offering a comprehensive understanding of the congregation’s enduring legacy.

The Transition to Reform Judaism

In the late 19th century, Congregation Mickve Israel underwent a significant transition as it embraced the principles and practices of Reform Judaism. Influenced by the broader Reform movement sweeping through American Jewry, the congregation sought to modernize its religious services and adapt to the changing times.

The shift to Reform Judaism brought about changes in liturgy, music, and religious practices within Congregation Mickve Israel. The traditional Sephardic customs and rituals were gradually modified or replaced, reflecting the congregation’s desire to align with the progressive ideals of the Reform movement.

The Downside of the Transition

While the transition to Reform Judaism allowed Congregation Mickve Israel to align itself with the evolving Jewish landscape in America, it also brought about certain challenges and tensions. Some members who strongly identified with the Sephardic traditions and customs expressed concerns about the loss of their distinctive heritage.

The shift to Reform Judaism meant that certain practices and rituals rooted in Sephardic tradition were modified or discontinued, leading to a sense of cultural loss for some congregants. The emphasis on modernization and adaptation to contemporary practices created a divide between those who embraced the changes and those who longed to maintain a stronger connection to their Sephardic roots.

However, despite these challenges, the transition to Reform Judaism allowed Congregation Mickve Israel to remain a vital and dynamic center of Jewish life in Savannah. The congregation’s commitment to inclusivity and engagement with the wider Jewish community has fostered a sense of unity and shared purpose among its members.

Conclusion

Congregation Mickve Israel Synagogue stands as a symbol of resilience, religious freedom, and Sephardic cultural heritage. Its Sephardic roots, architectural grandeur, museum, and commitment to community engagement have left an indelible mark on the congregation and the city of Savannah. While the transition to Reform Judaism brought about changes and challenges, it also enabled the congregation to adapt and thrive in the modern era.

Preserving and celebrating institutions like Congregation Mickve Israel is essential for understanding and appreciating the vibrant tapestry of local history and cultural identity. The synagogue’s rich past, coupled with its continued relevance and engagement with the community, ensures that its legacy as a Sephardic-founded synagogue endures.