Maimonides – 12th Century

The next reference to the issue of eating dairy after meat was made centuries later, by Maimonides.[1] He rules like Mar Ukva, that meat and dairy cannot be eaten during the same meal, and adds a time barrier of six hours. He explains that six hours are needed to get rid of the meat which gets stuck between the teeth. As is typical for Maimonides, he does not explain why he chose to follow this opinion and to ignore Rabbi Shimon Kayara, and he also does not explain the source for the six-hours’ time barrier.

Rabbi Meir ben Yequtiel HaCohen (13th century, Germany), who represents the Ashkenazi practice, quotes in his commentary on Maimonides two leading Tosafists who interpret this Halakha differently:[2]

According to Rabbenu Yitzhak, when Mar Ukva spoke of another meal, he did not refer to breakfast and lunch or dinner… once the table is cleared and the blessing recited [after eating meat] it is allowed immediately [to eat dairy]… and Rabbenu Tam said that even in the same meal one is allowed to eat dairy after meat if he ate bread and washed his mouth in between…

Rabbi Yosef Karo – 16th Century

The last stop in our meat and dairy journey will be the Shulhan Arukh:[3]

If one ate meat, even meat of wild animals or fowl, he must wait six hours before eating cheese. And even if he waited six hours, if he found meat between his teeth he should remove it.

Rabbi Moshe Iserles, the Rema, writes the following regarding the Ashkenazi practice, which in his time already included Eastern Europe:

Some say that there is no need to wait six hours, and clearing the table is enough, in addition to saying Birkat Hamazon, eating something else, and washing the mouth. The widespread practice in these countries is to wait one hour after meat and then eat cheese.

Summary:

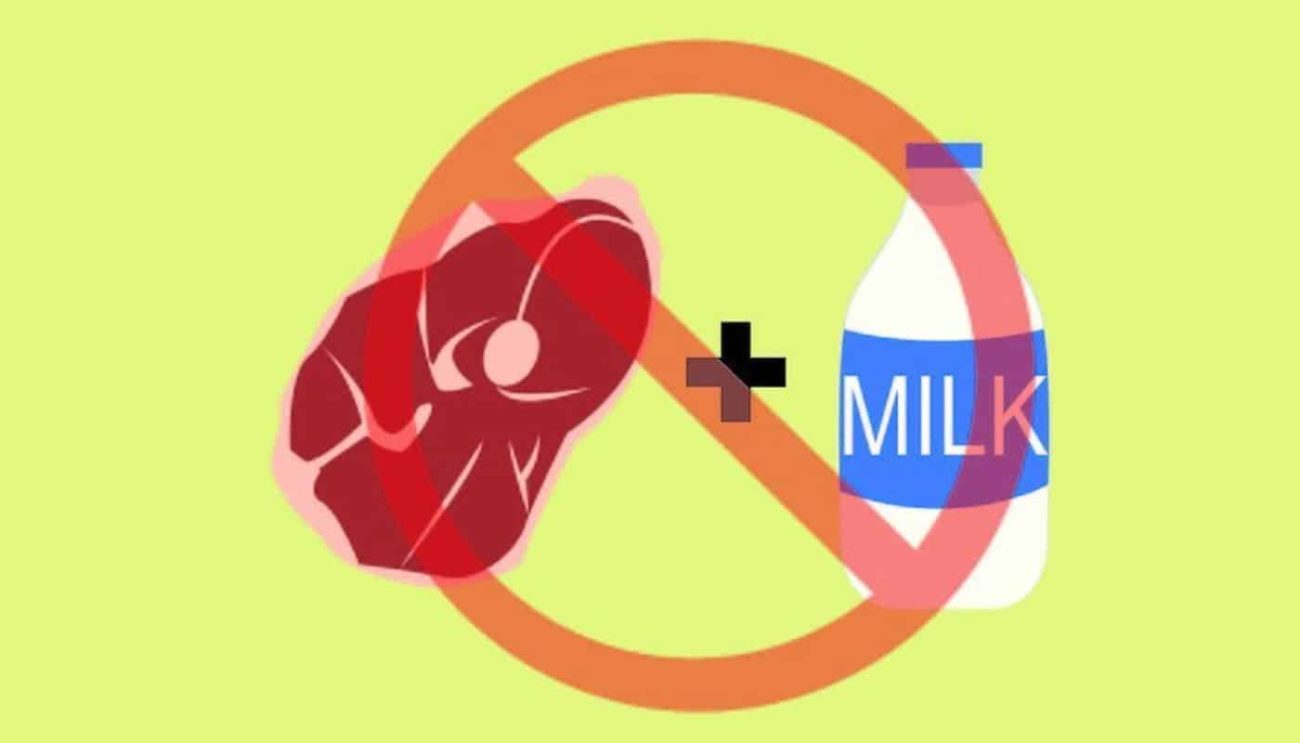

The Torah writes the prohibition in a somewhat enigmatic manner, but in Talmudic times the consensus is that cooking and consuming meat of domestic animals with milk is biblically forbidden. There is a dispute whether wild animals’ meat is forbidden by the Torah or by rabbinic decree, but all agree that fowl with milk is a rabbinical fence.

Up until the third century there were several enclaves in Israel and Babylonia where cooking and eating fowl with milk was allowed by decree of the local rabbis.

Around that time, the idea of additional separation has evolved in Babylonia. Few scholars went to extremes such as forbidding eating dairy after meat without waiting for the next meal, or even the next day. Despite all this, the prevalent practice, documented in the ninth century, was to wash hands after meat, and then eat cheese immediately, even during the same meal.

In the 12th century, Maimonides rules, against the prevalent practice, that one must wait six hours between meat and dairy. His opinion is amplified in the 16th century by Rabbi Yosef Karo, who requires four levels of separation between meat and dairy:

1) waiting six hours; 2) eating something else in between; 3) tooth-picking; 4) saying Birkat HaMazon after the first meal;

Ashkenazi scholars opposed both Maimonides and the Shulhan Arukh. In the 12th century the Ashkenazi practice was to eat dairy after meat with only Birkat HaAmazon or hand-washing as separation. In the 16th century Ashkenazim became a little stricter and required a one hour barrier between the two, with some scholars speaking of three and four hours.

When we come to talk of modern times, one must admit that we face special challenges. Our work and eating habits are different, we consume processed foods marked as dairy, and we need our coffee. Can one then choose to follow Talmudic law, or the ruling of the Ashkenazi rabbis of the 12th or 16th century, instead of adhering to the very limiting measure of six hours of separation?

The answer is that though we try to follow our forefathers’ practice, no one can argue that following the Talmudic custom, or the Ashkenazi custom, which is stricter, would be considered breaching the law. One should consider the advantages and disadvantages of the different practices, and might decide to act differently in accordance with circumstances and environment (e.g. work, friends, children, when traveling etc.)

[1] רמב”ם, הלכות מאכלות אסורות, פרק ט הלכה כח: מי שאכל בשר בתחלה בין בשר בהמה בין בשר עוף לא יאכל אחריו חלב, עד שיהיה ביניהן כדי שיעור סעודה אחרת. והוא כמו שש שעות מפני הבשר של בין השינים שאינו סר בקינוח

[2] הגהות מיימוניות, הלכות מאכלות אסורות, פרק ט הלכה כח: רבנו יצחק פירש שאינו מדבר בסעודה שרגילין לעשות אחת שחרית ואחת ערבית, אלא אפילו מיד, אם סילק תכא [שולחן] ובירך מותר… ורבנו תם אמר הא דאסר עד סעודה אחרת היינו אם לא קינח והדיח אבל אם קינח והדיח אפילו בהא סעודה שרי

[3] שולחן ערוך, יורה דעה, הלכות בשר בחלב, סימן פט סעיף א: אכל בשר, אפילו של חיה ועוף, לא יאכל גבינה אחריו עד שישהה שש שעות. ואפילו אם שהה כשיעור, אם יש בשר בין השינים, צריך להסירו… הגה:… ויש אומרים דאין צריכין להמתין שש שעות, רק מיד אם סלק ובירך ברכת המזון, מותר על ידי קנוח והדחה והמנהג הפשוט במדינות אלו להמתין אחר אכילת הבשר שעה אחת, ואוכלין אחר כך גבינה. מיהו צריכים לברך גם כן ברכת המזון אחר הבשר דאז הוי כסעודה אחרת, דמותר לאכול לדברי המקילין…