Whomever has those three character traits… jealousy, arrogance, and an insatiable soul, is a disciple of Balaam the wicked.

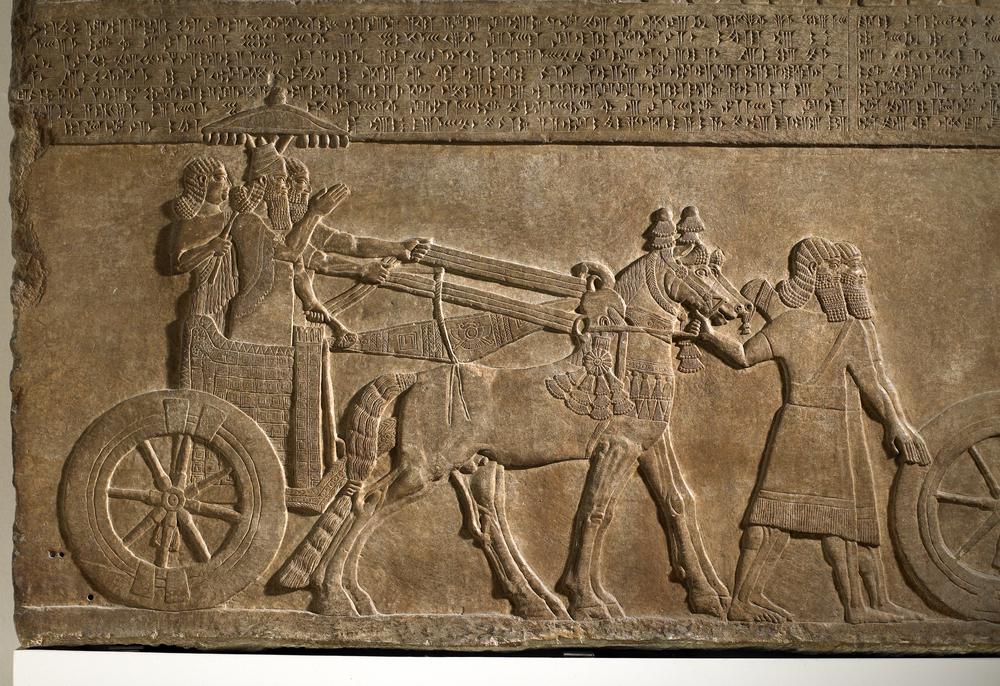

This Mishna concisely describes the shortcomings of Balaam, a man who is referred to in the Torah as both a prophet and a sorcerer. He is a man who seems to possess tremendous knowledge and who is able to converse with God, albeit in dreams or after certain preparations. Balaam, whose name is derived from the Hebrew word for “swallow”, is never happy with what he has. Once he is offered a contract by Balak, a contract on the lives of hundreds of thousands of innocent people which can bring great riches, he cannot bring himself to walk away. Even after God repeatedly admonishes him against harming the Israelites he tries to find ways to carry out his plans and collect a handsome fee from Balak.

At the end of the day, though, Balaam returns home empty-handed and shamed. He tried to swallow more than he could digest and from the elevated status of a prophet nothing remains but a sorcerer, pretending to have knowledge and prying on people’s darkest fears. Balaam eventually joins the war against the Israelites and is killed in battle.

As the Torah zooms out of the battlefield, with the image of the slain sorcerer, we understand that even a person with towering intellectual qualities can fall prey to his own greed, jealousy, and arrogance. The Mishna reminds us that in order to avoid Balaam’s pitfalls and to follow the path of our forefathers we should appreciate what we have, respect each other, and understand that we were given our strengths and talents so we can help others.

On that note, let me tell you a little bit about our educational effort.

I am heading now back home to Rockville, Maryland, after spending twelve days in Los Angeles. It was a great opportunity to meet new friends and reconnect with old ones, and this brief period was also packed with Torah and learning.

I was blessed to be invited to teach again at my beloved Academy for Jewish Religion. The course, Introduction to Midrash, is not for the faint of heart (or rather, patience) as it includes 20 lectures totaling 30 hours, but if you are intrigued by certain statements in Midrash, maybe you would like to listen to it.

The course, as well to other classes I have given and a collection of Sephardic liturgy, can be found on www spReaker.com (search for my name). You could also download the spReaker app, sign up, and follow, if you wish.

In L.A. I also had the pleasure to speak at several parlor meetings and to co-host a discussion on Sephardic culture and Halakha with Rabbi Daniel Bouskila, director of the Sephardic Educational Center.

I also addressed a crowd of young professionals at Nessah Israel Congregation in Beverly Hills, discussing the unique qualities of the Sephardic halakha and its approach to life (all these classes and the Midrash course will be available on spReaker on Monday).

In all classes and encounters, I hear the same question. I was also asked to address that question, from different angles, in talks in London at the end of the summer and in Brooklyn before Rosh HaShana. The same question, in various reincarnations, surfaces from the many emails I receive with Halakhic and theological questions (you now understand why it takes me a day or two to respond).

The question is: why are young people disenfranchised with Judaism and what can we do to change the situation? The answer, is complicated. I currently deliver it orally, but I hope to be able to write it down after addressing readers’ questions about modesty, contraceptives, pricy Kosher meat, and more,

To be sure, there are the issues of the generational gap, globalization, accessibility of knowledge, and paralysis of the religious establishment, but above all we have the problem of not being able to enjoy life and Judaism simultaneously.

I am not saying that Judaism is about having fun, and there is no doubt that life is full of challenges, obstacles, and suffering. However, Judaism should be able to provide us with the greatest joy, that of knowing that one’s life has a purpose.

So for now, in order to answer the previous question, I must leave you two others we should ask ourselves:

What is the long term goal and the purpose I hope to achieve, in this life, by being observant?

How can I convince a non-observant or a non-Jewish friend to become an observant Jew?

I look forward to hear your input.