Shemot 2017

Righteous women! Because of their merit, the Israelites were redeemed from Egypt. This beautiful statement, found in the Babylonian Talmud (Sotah 11:2), suggests that women played a pivotal role in the Exodus. We read it and think “well, no one can claim that the Rabbis tried to marginalize women or ignore their contribution to society”. But let us read the whole story and see if this is an accurate assessment.

Rabbi Awera expounded: The Israelites were redeemed from Egypt because of the merit of the righteous women of that generation. When they would go to draw water, God would send small fish to their jars, and they would draw a jar filled with half water and half fish. They would go home and boil two cauldrons, one of water and one of fish, and would take the cauldrons to their husbands to the field. They would wash their husbands [with the hot water], anoint them with oil, feed them [the fish], and serve them [wine] to drink, and then lie with them between the cauldrons. When they would get pregnant, they would go back home, and when the time came to give birth, they would go to the field and give birth under the apple trees. God would send from heaven [an angel] to clean and wash them, just as an animal licks its newborn, and He would create for each baby two round stones, one streaming honey and the other oil. When the Egyptians saw the babies, they attempted to kill them, but they would disappear into the ground, to resurface again like grass. When they matured, they went to their homes in flocks, and when God revealed Himself at the Sea of Reeds, they were the first to recognize Him. (full Hebrew text in endnote).

We could read this story as an inspirational tale of women as leaders of a resistance movement. They are not willing to give up on their future and they keep having children. They have to convince and cajole their husbands, who otherwise would have decided not to bring new life to the house of bondage, and they are rewarded with miraculous intervention, as God Himself, with the angels, becomes the midwife and protector of the multitudes of newborns. When the Exodus culminates with the annihilation of the Egyptians in the sea, those babies, who have personally witnessed God’s greatness and presence, are the first to recognize him.

But the story, unfortunately, does not read like that. The Midrash is written from the perspective of a man, who sees the role of women as mere vehicles for the physical production of the next generation. The women march to the fields, bringing food and comfort to their husbands, who are the backbone of the nation. After they get pregnant, they return to the field to deliver their babies. The babies are not born at home, but rather in the open field, and are fed by two round stones, a cold replica of a nursing mother. There is no motherly love, warmth, or lullabies (who can forget Ofra Haza’s “hush now my baby” lullaby, in The Prince of Egypt?). Then, left by their mothers at heaven’s mercy, and attacked by the Egyptians, they spring forth like grass and return to their homes in droves, like animals. The headline of the Midrash, speaking of the righteous women, stands in stark contrast to its content, which focuses on the manly worldview of women as a means for men to produce offspring, and of their responsibility to take good care of their husbands.

What we have here, I believe, is a two-layer story. The core of the Midrash is the statement that the redemption was in the merit of the righteous women. That statement referred to five specific women: the midwives Shifra and Puah, Moshe’s mother Yokheved and his sister Miriam, and Pharaoh’s daughter. These five women were instrumental, each in her own way, in the orchestration of the future redemption. The second layer, possibly added by Rabbi Awera, took the story to the realms of myth and fantasy. It was part of the general agenda of Midrashic sages to try and uplift the spirit of Jews, especially after the incessant stream of catastrophes in Israel since the destruction of the Temple, which included the fall of Masada, the failed Rebellion of the Diaspora (112-115), the tragic Bar Kokhva revolt (132-135), the declaration of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire (4th c), and the abolishment of the institution of Beth Din and president (5th C). The author of the Midrash felt that Jews cannot stand up to the mighty Roman Empire, and that the only way to survive and persevere is to rely on God’s miraculous intervention and on natural growth. Instead of advocating courageous actions of defiance, such as those of the five women, the Midrash preaches for growing the population quietly and steadily. It is the kind of “plan” used by poor or oppressed populations as a last resort.

That message might have served Jews well in the past, but it is not in place today. It is degrading for women, and it brushes aside the importance of genuine love and intimate relationships between parents and children. It presents the next generation as a tool in the war against our enemies, something we expect to hear from fanatic religious leaders. We also understand today that uncontrolled population growth is dangerous and unsustainable, and that family planning is essential for the survival and development of human society. Finally, we must shed the exilic mentality of the helpless and persecuted, whose only strength is in being fruitful and multiplying. We must focus our efforts of education in finding the positive messages Judaism has to offer, and in showing that following them can contribute to our personal growth and success and to making the world a better place for all.

Imagine if we could interview Yokheved, Moshe’s mother, and hear from her how does she see the role of a righteous woman and how she feels about this Midrash…

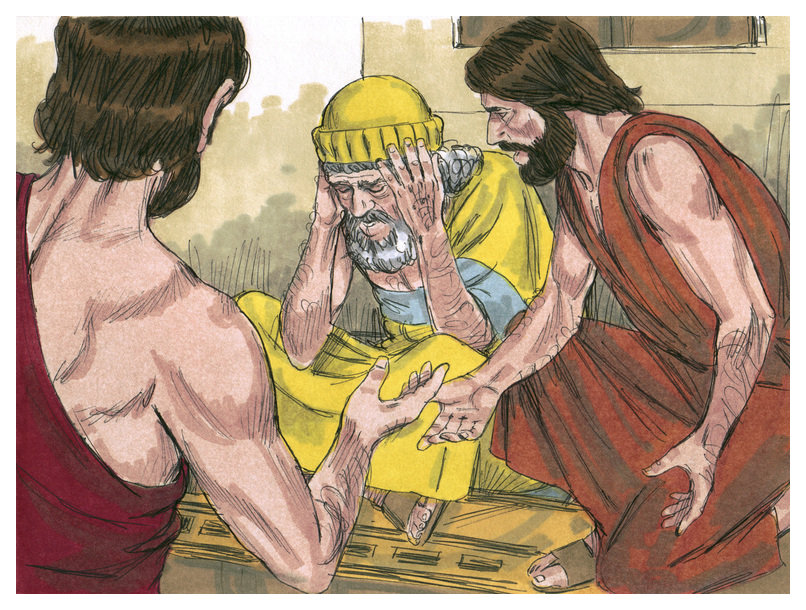

Yokheved: I am so glad you brought up this question, as I feel that the voice of women has been silenced. Ever since the publication of that legend, about us women producing an army of 600,000 men, I feel very uncomfortable. My own grandchildren assault me with requests to tell them about the time when I’d take the pots of boiling fish and water to grandpa at the field! Am I supposed to repeat the myths of washing and feeding the men, and then, you know, I don’t want to get into details? Really? Between the pots, in the field? Who does that? It’s terrible! Besides that, who boils fish? But I’m getting carried away with minutiae. What bothers me is that this story portrays us women as nothing more than husband-pleasing, meal-cooking, baby-producing machines. What inspiration can we give our future generations? How can we expect them to become righteous women one day?

(Yokheved falls silent for a moment, pensive, then continues:) Let me tell you what the true character of a righteous woman is: she reveres only God, she is strong and unyielding, and she emanates love and compassion. And let me tell you who are the righteous women who brought forth the redemption, because they have names!

The first two, the heroes, the role models, are of course Shifra and Puah. Such powerful women! It was so easy and convenient to fold under the pressure of Pharaoh and say that they were just following orders. They risked their lives by defying him, and showed the whole world and future generations, that sacrificing the lives of others to save your own is an unforgivable sin, which cannot be justified as obedience to the commands of a tyrant.

Their quiet and resilient victory led me to the decision to keep my baby and fight for his survival against all odds. I looked for a barren Egyptian woman who would be willing to adopt a Hebrew infant left on her doorstep, and the Hebrew maids in the palace informed me that the princess is a candidate. We put him in a basket and planted it among the reeds near the princess’ favorite bathing spot, and once she took the bait, Miriam, in her audacity, convinced her to have me as a wet-nurse.

If not for the courage and astuteness of the princess, the mission would fail. My Hebrew maids’ network told me how Pharaoh was dumfounded when she presented her new son to him. He wanted to kill him on the spot, but she played the role of daddy’s spoiled little girl in a very convincing way, throwing tantrums, screaming, and then falling quiet and unresponsive. The man never stood a chance. He caved in, let her have the baby and have me as his wet-nurse. And nurse him I did, with stories of our glorious past, of our forefathers and especially my grandfather Jacob. I fed him stories of the Promised Land and the suffering of his brethren. I told him of the courageous women who risked their lives so he could live. He knew all about the cruel enslavement and was more inspired than anyone to lead the nation to freedom. When he went out that day to see the suffering of his brothers, he carried with him the names and lessons of the important and righteous women in his life: Shifra, Puah, Yokheved, Miriam, and Pharaoh’s daughter.

This imaginary interview with Yokheved reaches its end, and we, 21st century readers, understand that great women do not stand behind great men. They stand before, in front, and ahead of them. They give them life, love, education, values, and aspiration. Moshe would not have existed and would not have been the great and passionate leader he was, without the shield of love of his biological and adoptive mothers, without the resilience and courage of Shifra, Puah and Miriam, and without the personal lessons he learned from all of them. We shall keep following in the footsteps of those courageous women who by wit and wisdom, courage and faith, have managed to defeat empires, and pray that we too will merit to have such righteous women in our midst and that we will be able to emulate them. They taught us, above all, that righteousness and greatness do not start with miracles but with the human spirit which recognizes the image of God, the right to freedom and human dignity, and the responsibility of everyone to rise to the task.

Sources:

- דרש רב עוירא: בשכר נשים צדקניות שהיו באותו הדור נגאלו ישראל ממצרים. בשעה שהולכות לשאוב מים, הקדוש ברוך הוא מזמן להם דגים קטנים בכדיהן ושואבות מחצה מים ומחצה דגים. ובאות ושופתות שתי קדירות אחת של חמין ואחת של דגים, ומוליכות אצל בעליהן לשדה. ומרחיצות אותן, וסכות אותן, ומאכילות אותן, ומשקות אותן, ונזקקות להן בין שפתים. וכיון שמתעברות באות לבתיהם, וכיון שמגיע זמן מולדיהן, הולכות ויולדות בשדה תחת התפוח. והקב”ה שולח משמי מרום מי שמנקיר ומשפיר אותן, כחיה זו שמשפרת את הולד, ומלקט להן שני עגולין אחד של שמן ואחד של דבש. וכיון שמכירין בהן מצרים באין להורגן, ונעשה להם נס ונבלעין בקרקע, ומביאין שוורים וחורשין על גבן, ולאחר שהולכין היו מבצבצין ויוצאין כעשב השדה, וכיון שמתגדלין באין עדרים עדרים לבתיהן, וכשנגלה הקדוש ברוך הוא על הים הם הכירוהו תחלה

- The attitude towards women as either sexual objects or children-producing machines continues throughout the discussion in the Talmud there (Sotah 11:2-12:1), but this is out of the scope of this article.

- There is also a midrash, cited by Rashi, that women delivered sextuplets in each birth. This Midrash is dispelled by the simple fact that there are only seven families whose Egypt-born children are mentioned by name (all the other censuses are of the descendants of Jacob). Those families are the families of Amram, Yitzhar, Uziel, Korah, Aaron, Moshe and Tzelofhad – with 2-5 children each, and an average of 3.3, from multiple pregnancies. In addition, the Torah records only two multiple births, in both cases twins, and the Torah makes a big deal about them: Esau and Jacob, Peretz and Zerah. That’s it! If there was ever a sextuplet, we could have expected the Torah to address it in a verse along the lines of: וימלאו ימיה ללדת והנה ששיה בבטנה, ותאמר לה המילדת אל תיראי כי גם זה וזה וזה וזה וזה לך בן, וגם בת אחת – “…and when the time came for her to give birth, behold, there were sextuplets in her belly, but the midwife said: fear not, for this also is a boy, and this one, and this one, and this one, and this one, and one girl.”