| Name | Moses Maimonides |

|---|---|

| Birthdate | March 30, 1135 |

| Place of Birth | Cordoba, Spain |

| Sephardic Heritage | Yes |

| Father’s Name | Rabbi Maimon |

| Date of Death | December 13, 1204 |

| Place of Residence | Fes (Morocco), Fostat (Egypt), Cairo (Egypt) |

| Fields of Expertise | Philosophy, Medicine, Jewish Law |

| Major Works | “Mishneh Torah,” “Guide for the Perplexed” |

| Contributions | Integrated Aristotelian philosophy with Jewish thought, Established Jewish legal principles, Reconciled reason and faith |

| Profession | Philosopher, Physician, Legal Scholar |

| Notable Accomplishments | Prominent leader within the Sephardic Jewish community, Physician to Vizier and Sultan Saladin |

| Legacy | Influential figure in Jewish thought, Continues to inspire generations of scholars and thinkers |

Additional Interesting Facts:

- Maimonides’ family fled Spain due to persecution and settled in various cities, including Fes, Morocco, and eventually Cairo, Egypt.

- He served as the personal physician to the vizier, Al-Qadi Al-Fadil, and later to Sultan Saladin, the renowned military leader.

- Maimonides faced personal hardships, including the loss of family members during migration and his own battle with asthma.

- His works, such as the “Mishneh Torah” and the “Guide for the Perplexed,” continue to be studied and revered worldwide.

- Maimonides’ formulation of the Thirteen Principles of Faith, known as the “Ani Ma’amin,” remains a central part of Jewish liturgical texts.

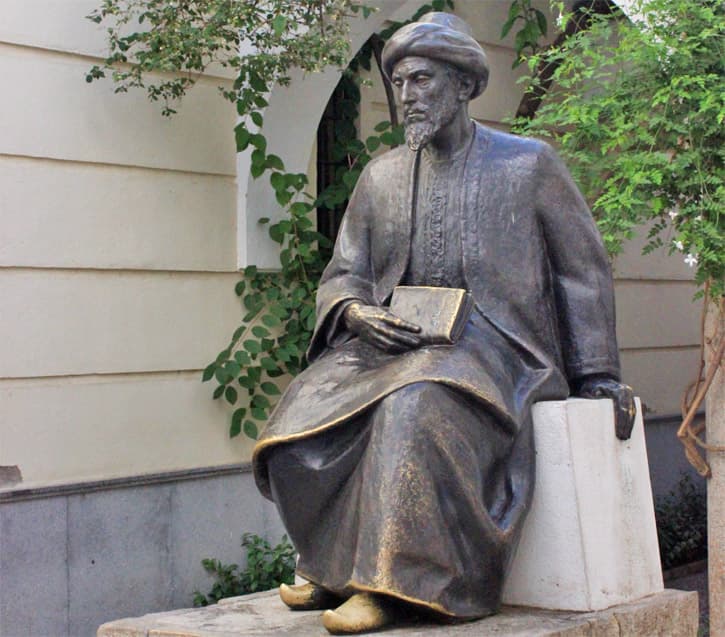

Moses Maimonides, also known as Rambam, was a remarkable figure in Jewish history, renowned as a philosopher, physician, legal scholar, and influential leader within the Sephardic Jewish community. He was born on March 30, 1135, in Cordoba, Spain, into a distinguished Sephardic Jewish family with a long lineage of scholars and leaders.

Growing up during a time when Islamic rule flourished in Al-Andalus, Maimonides benefited from the intellectual and cultural exchange between Muslims, Jews, and Christians. His early education focused on Jewish texts, including the Torah, Talmud, and works of Jewish law. However, Maimonides’ thirst for knowledge extended beyond the realm of Jewish scholarship, delving into a wide range of subjects such as philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.

Tragedy struck Maimonides’ family with the rise of the Almohad dynasty, a fundamentalist Islamic regime that imposed strict religious observance. In 1148, fearing persecution, the family was compelled to flee Spain. They embarked on a journey across various North African cities, eventually settling in Fes, Morocco. Despite the challenges of upheaval and displacement, Maimonides’ intellectual pursuits continued to thrive as he immersed himself in the study of Jewish texts and secular disciplines.

Under the guidance of his father, Rabbi Maimon, a renowned scholar himself, Maimonides’ intellectual prowess and passion for learning flourished in Fes. His studies expanded beyond Jewish law, encompassing subjects such as philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. This wide-ranging knowledge allowed Maimonides to draw from diverse sources and engage with the broader intellectual currents of his time.

In 1165, seeking greater stability and opportunities, Maimonides and his family migrated to Egypt, eventually settling in Fostat (present-day Cairo). Egypt became the backdrop for Maimonides’ most significant achievements and contributions. While establishing himself as a physician, he also emerged as a prominent leader and scholar within the Sephardic Jewish community.

Maimonides’ reputation as a physician grew, leading him to serve as the personal physician to the vizier, Al-Qadi Al-Fadil, and later to Sultan Saladin, the celebrated military leader. His medical expertise earned him respect and admiration from both Jewish and Muslim communities. Maimonides authored numerous medical treatises, including “The Treatise on Asthma” and “The Regimen of Health,” which not only had a lasting impact on medical practice but were also translated into various languages, becoming influential texts across cultures.

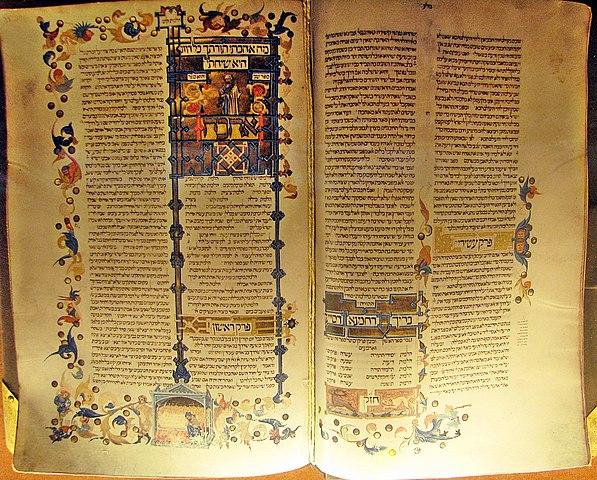

Despite the demands of his medical practice, Maimonides dedicated substantial time to his scholarly pursuits. His most influential works include the “Mishneh Torah” and the “Guide for the Perplexed.” Completed around 1180, the “Mishneh Torah” is a comprehensive code of Jewish law that encompasses all aspects of Jewish life and practice. It provided clear, systematic guidelines and established Maimonides as a preeminent legal authority. His legal expertise also extended to the realm of responsa, where he wrote numerous responses to specific questions posed by individuals and communities seeking his guidance on matters of Jewish law and practice.

The “Guide for the Perplexed,” completed in 1190, addressed philosophical and theological questions arising from the tension between reason and faith. Drawing upon his deep understanding of Jewish texts, Aristotelian philosophy, and mystical traditions, Maimonides sought to reconcile religious teachings with rational inquiry. This monumental work profoundly influenced Jewish philosophy and had a lasting impact on philosophical discourse not only within the Jewish world but also beyond it, influencing Christian scholasticism and Islamic thought.

Maimonides’ writings were not without controversy. Some of his philosophical ideas faced criticism and provoked debates among scholars. Nevertheless, his emphasis on intellectual rigor, rationalism, and the integration of secular knowledge with religious teachings left an indelible mark on Jewish thought and philosophy.

Beyond his intellectual contributions, Maimonides faced personal hardships throughout his life. He experienced the loss of family members during the tumultuous period of migration and persecution. He also battled health issues of his own, including asthma, which he endured throughout his life.

Maimonides’ influence extended beyond the realm of scholarship. His impact on Jewish liturgy is notable, as he formulated the Thirteen Principles of Faith, known as the “Ani Ma’amin,” which became a central part of Jewish liturgical texts. It is recited in many Jewish communities as a declaration of faith, reinforcing Maimonides’ enduring influence on Jewish religious practice.

Moreover, Maimonides’ commitment to education and the dissemination of knowledge played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of Jewish scholarship. His works became essential texts studied in yeshivas and academies, shaping the curriculum of Jewish learning for centuries. His dedication to education laid the groundwork for the flourishing of Jewish intellectual traditions.

Maimonides’ writings also included a comprehensive commentary on the Mishnah, known as the “Perush HaMishnayot.” This work provided insights, explanations, and clarifications on the complex legal discussions found in the Mishnah, contributing to the understanding and study of Jewish oral law.

His teachings extended to the realm of ethics. Maimonides’ treatise “Eight Chapters” (“Shemonah Perakim”) explored various ethical principles and virtues, emphasizing the importance of ethical conduct, personal character development, and the pursuit of moral excellence. These teachings continue to guide individuals in their personal and communal ethical practices.

It’s important to acknowledge the cultural and historical context in which Maimonides lived. He witnessed the clash of civilizations between Muslims, Christians, and Jews, as well as the shifting political landscape that impacted Jewish communities. These circumstances influenced Maimonides’ intellectual development, his engagement with different cultural traditions, and his efforts to address the challenges faced by the Jewish community.

The Legacy Of Maimonides

Maimonides’ legacy endures as a testament to the enduring power of knowledge and the pursuit of wisdom. His works continue to be studied, revered, and debated by scholars, theologians, and philosophers worldwide. His impact on Jewish thought, philosophy, ethics, science, and historical contexts remains profound, shaping the development of Jewish intellectual traditions and influencing broader intellectual discourse. Moses Maimonides remains an icon of Jewish intellectual history, revered for his deep wisdom, compassion, and commitment to seeking truth and understanding in both the spiritual and secular realms. His life journey reflects the resilience and determination of the Jewish people in the face of adversity, as he navigated political turmoil, migration, and cultural exchange.

In conclusion, Moses Maimonides stands as an enduring figure in Jewish history, leaving an indelible mark through his intellectual achievements, leadership, and contributions to various fields. His works continue to inspire and influence generations of thinkers, shaping the development of Jewish thought and philosophy. Maimonides’ unwavering commitment to knowledge, ethics, and the pursuit of truth serves as a beacon of inspiration for individuals seeking wisdom and understanding in their own lives.

Learn more about other Notable Sephardic Jews

Parashat Behar – Weekday Torah Reading (Moroccan TeAmim)