We tend to think that Avraham sent his servant to Haran to find Yitzhak a woman from Avraham’s family. I would like to prove that Avraham had no such intention, and that finding Rivka, who was related to Avraham, was a bonus point for the servant.

I believe that Avraham turned to Haran not because its people were morally superior to the Canaanites, but rather because a local girl would be given to the influence of her family and would not accept the new theology heralded by Avraham. Avraham needed to import a bride from a far-flung land, and the first place he thought of was Haran, where he had a clan and an extended family, but he never instructed the servant to go to Avraham’s family.

Already our sages noted that by saying that the idle talk of the servants of the fathers is better than the Torah of the sons (Bereshit Rabbah). They wanted to draw our attention to the subtle changes the servant makes in telling Rivka’s family of his mission and of his encounter with Rivka.

Those changes, as we shall see, were needed to convince the family to let the girl leave with a complete stranger, to a country from which she will probably never return, to marry a man they will never see.

Let us compare the story as it happened and as the servant tells it to the family. First, the story as it happened (Gen. 24:1-26):

- Avraham tells the servant: Do not take a woman for my son from the Canaanites in whose midst – בקרבו, I dwell (24:3).

- Avraham tells the servant: Go to my land – ארצי, and to my clan – מולדתי (24:4). Avraham repeats the warning in 24:8.

- In response to the servant’s question as to what will happen if the woman refuses to follow him, Avraham says: Be warned – never take my son back to that land – Haran (24:6).

- In continuation, Avraham speaks of God who took him away from his father’s home and from his clan (24:7).

- Avraham speaks of a scenario in which the woman refuses to follow the servant (24:8).

- In that case, he says, the servant will be absolved of the oath (24:8).

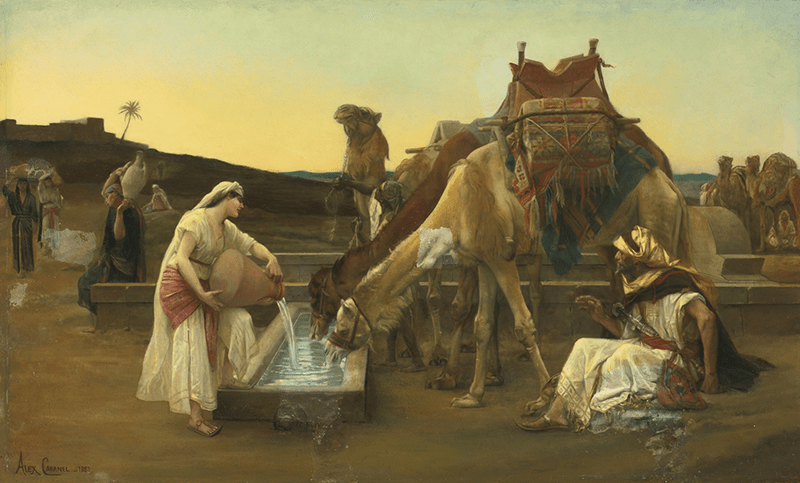

- When the servant arrives at Haran, he asks God to help him find a bride. He uses the word הקרה, which means coincidence, or randomly. He does not look specifically for Avraham’s family (24:14).

- After Rivka draws water for all the camels, the servant places jewelry on her nose and her arms, before asking her for her name (24:22).

This is the story as told by the servant to Rivka’s family (Gen. 24:34-49):

- The servant changes the word בקרבו to בארצו – in whose land I dwell. Avraham’s concern was the physical closeness with the Canaanites, but the servant turned it into a political problem, insinuating that Avraham and the Canaanites are of different nations (24:37). This comes after a long introduction about Avraham, his wealth, and how Yitzhak, the only son (!), inherited all that wealth.

- Instead of land and clan, the servant says that Avraham said בית אבי ומשפחתי, my nuclear and extended family. He alludes that Avraham wanted to find a bride from his own family (24:38).

- The servant omits Avraham’s double warning not to take Yitzhak back to Haran. That will not sit well with the Haranite branch of the family.

- Instead of “God who took me from my father’s home”, the servant speaks of “God with whom I walked”. This is meant to avoid tension between the family and Avraham, who left his family by the word of an unknown God (24:40).

- Instead of speaking of the refusal of the woman, the servant speaks of the refusal of the family to let her go, thus placing the weight of the decision on Rivka’s family (24:41).

- Instead of oath – שבועה, the servant uses the word אָלָה – a vow whose transgression brings a curse. He does that to scare the family into agreeing (24:41).

- Instead of הקרה – randomly, the servant refers to דרך – path, twice (24:40, 42) דרך אמת – true path, once (24:48). He wants to emphasize that he had a clear path, and that God lead him in that path to Avraham’s family. He also says that if they disagree, he will have to veer to the right or the left, again alluding to the true path (24:49).

- In the servant’s rendition of the events, he first asked Rivka for her name and only then placed the jewelry on her nose and arms.

The answer of Rivka’s brother and father says it all: It is God’s will. We cannot respond with evil or good words. That means that they would have wanted to say something, but they are afraid (compare Lavan’s words in 31:29).

One might argue that the family was not willing to let Rivka go without a fight, since on the following morning they suggested to ask Rivka whether she wants to go with the servant. In my opinion, that happened because they did not receive the dowry they were hoping for. The family received only sweets, while Rivka received gold, silver, and garments, which would eventually return with her to Yitzhak’s house (24:53).

What lessons can we learn from this story?

- The Torah’s narrative is extremely intricate and calculated. It invites to delve deeper and pay attention to little details and nuanced deviations.

- One can recount things as they were, yet completely misrepresent the events. We have to be careful when telling a story or listening to it. Are we distorting reality? Are we hearing one’s version of the events?

- Avraham wanted to alienate his future daughter-in-law from her relatives and their influence. It teaches us that it is hard to educate in a hostile or contradicting environment.

However, regarding the last point I have my doubts. Did Avraham’s plan succeed as he hoped? Isn’t it possible that Rivka’s miscommunication with her husband stemmed from her frustration of being yanked from her roots and brought to Canaan? And eventually, Yaakov did go to Haran, and his children, the future Tribes of Israel, were born there.

These are questions which are hard to answer, and like many of the narratives of Bereshit, they leave us thinking of how our plans and calculations might work well or backfire, and of how unpredictable human nature is.

Shabbat Shalom

Questions for Kids: Parashat Chaye Sarah

שְׁ אֵ לֹות לְׁ פָרָ שַׁ ת הַׁ שָ בּועַׁ: חַׁ יֵי שָ רָ ה

- How old was Sarah when she died?

- Where was Sarah buried?

- Where did Avraham send his servant, and for what purpose?

- What did the servant take with him for the journey?

- What did the servant ask of HaShem?

- Who came to the well when the servant and the camels were there?

- What did she offer?

- What did the servant ask Rivka?

- What did the servant ask of Rivka’s family?

- Did Rivka agree with the servant’s request?

- Who was Yitzhak’s wife?

- How old was Avraham when he died?

- Who took care of Avraham’s burial?

- Where was Avraham buried?

Answers for Parashat HaShavua

Parashat Haye Sarah

- 127 years.

- The Cave of Machpelah in Hebron. מְעָרת הַמכְפֵּלָה

- To Haran. To find a bride for Yitzhak.

- Ten camels carrying gifts from Avraham.

- To help him find a bride for Yitzhak.

- Rivka.

- She gave water to the servant and offered to draw water from the well for all the camels.

- He asked her who are her parents and if they have room for him and his people to spend the night.

- To let Rivka go back with him to Canaan so she can marry Yitzhak.

- Yes.

- Rivka.

- 175

- Yitzchak and Yishmael.

- The Cave of Machpelah in Hebron. מְעָרת הַמכְפֵּלָה

Parasha Pointers: Chaye Sarah

Introduction: in this Parasha we find two excellent negotiators. In chapter 23 Avraham convinces the Hittites to sell him a burial plot, rather than giving it as a gift. In chapter 24, Avraham’s servant convinces Rivkah’s family to let her go with him to an unknown land and a relative who disappeared years ago. The pointers will focus on those two negotiations:

- Avraham’s opening remark is that he is a sojourner, a temporary resident.

- Avraham asks for אחוזה ,a word stemming from the root אחז ,which means to hold. Avraham wants a burial site which will become his stronghold, his claim for citizenship.

- To understand the significance and intent of Avraham’s request, think of how we connect to burial sites, personal or national.

- The Hittites answer that Avraham is a respected nobleman and that they will be glad to allow him to use their burial site. They are dodging his request by offering a gift. The burial site will remain Hittite property.

- Avraham bows down and addresses הארץ עם ,the noblemen. He wants to put them under pressure as the burial is delayed.

- He requests that they talk to Ephron. He could have done it himself, privately, but he wants to pull Ephron into the open and leave him no choice but selling the field.

- Ephron responds, like his fellowmen before him, that he will give the field as a gift. He will maintain the title of ownership.

- Avraham refuses politely and insists on paying. Ephron names an exorbitant price with the hope of deterring Avraham but fails. Avraham purchases the field.

- During this process the verb שמע ,hear, listen, or accept, appears six times.

- In the story of finding a bride for Yitzhak, note that the servant’s name is never mentioned, though most commentators assume it was Eliezer.

- Avraham is not interested in his family particularly. He just wants to import a bride, because he wants her to adhere to his teachings, and a local woman will be influenced by her family.

- He asks the servant to go to Haran because it will be easier to convince people who know Avraham to let a girl go to a far land and an unknown groom.

- Avraham does not specify family, but rather says מולדתי ואל ארצי אל ,my land and my birthplace (24:5).

- The servant says that he was told משפחתי ואל תלך אבי בית אל – my father’s household and my immediate family (24:38). This is his first step in the attempt to convey that Avraham insisted on someone from the family and that there will be dire consequences if she refuses to come.

- Avraham asks the servant to commit with שבועה – an oath (24:3, 8), but the servant says he committed to אלה – an oath with a curse (24:41). The servant implies that if the family refuses to let Rivka go the curse will dwell on them.

- When the servant asks whether he should take Yitzhak back if the woman refuses to follow him, Avraham answers with harsh words – שמה בני את תשיב פן לך השמר) 24:6), beware, do not dare take my son back to that land, but when the servant tells the story he omits these words which could offend the family, and focuses on the confidence Avraham had in his success (24:40).

- Avraham refers to God as מולדתי ומארץ אבי מבית לקחני אשר – He who took me from the house of my father and from my birthplace (24:7). These words would not sit well with the family since they insinuate detachment. Instead the servant cites Avraham as saying לפניו התהלכתי אשר’ ה – God in front of whom I have walked.

- Avraham says ללכת האשה תאבה לא אם – if the woman refuses to follow you (24:8), but the servant makes it the family’s decision, and bookends it with the fictitious curse: then be will you – אז תנקה מאלתי כי תבוא אל משפחתי ואם לא יתנו לך והיית נקי מאלתי absolved of my curse, when you come to my family, and if they will not give you [the

woman], you will be absolved of the curse (24:41). - This theory explains why the servant went to the water well instead of heading to Avraham’s family. The bride could have been any girl from Haran, and he was extremely lucky to find a relative.

- The servant gives Rivka jewelry before learning her identity (24:22-23) but tells the family that he first asked for her name (24:47). He changes the order of his actions to corroborate his claim that Avraham wanted a bride from the family.

- The response of Lavan and Bethuel in 24:50-51 gives the impression that they were cornered.

- They probably expected wonderful gifts from the servant’s coffers, but all the gifts were given to Rivka, while they only received candies and pastries (24:53).

- This could be the reason that they tried to hold Rivka back on the following day. Maybe they hoped to negotiate a better deal.

- Rivka is the one who decides to go, but the damage is already done. She realized that her family was willing, because of greed, to ship her away without asking her. This realization might have influenced her future relationships with Yitzhak. Though there is great love between them, she works behind his back, possibly because she feels that a

woman’s voice will not be heard. - When Yitzhak marries Rivka, it is written that he is forty years old, but nowhere is it written that she is three years old. Teaching this Midrash based idea to our children, and even to adults, is preposterous. The Midrash is based on the juxtaposition of the stories of the Akedah, Rivka’s birth, and Sarah’s death, and assumes they all happened at the

same time. This, of course, is incorrect. As in any narrative, the author highlights important moments that could have taken place years apart. - In that vein, how old do you think Rivka was when she got married?

Enjoy reading and learning.

Shabbat Shalom