The Mishkan Today

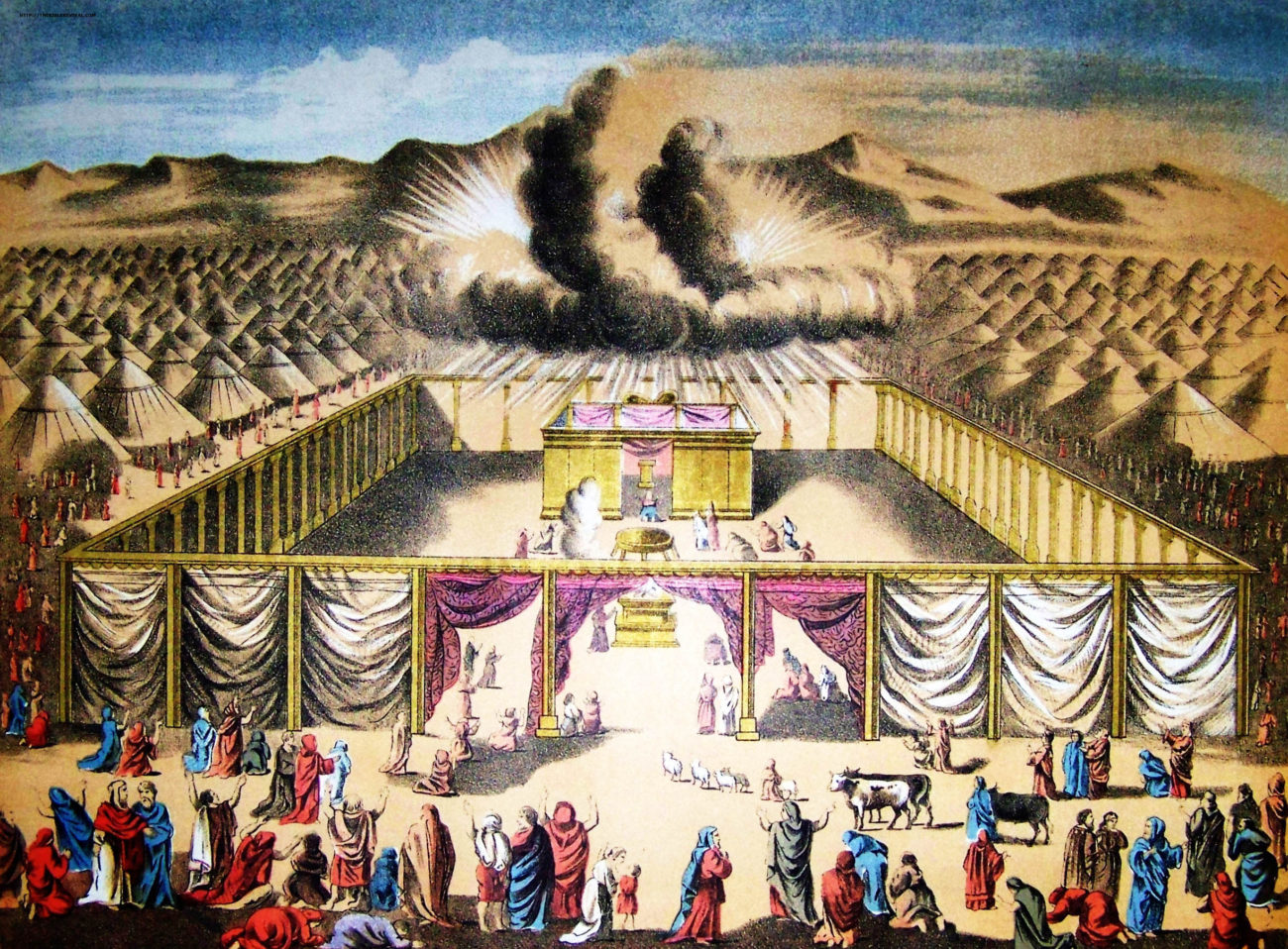

Parashat Pekudei concludes the detailed description of the construction of the Mishkan, which stretches over 14 chapters and 550 verses. The Mishkan served the Israelites in the desert and then wandered with them into and inside The Promised Land. The Mishkan moved from place to place until King Solomon finally built a permanent structure, the Temple. That was almost 3,000 years ago, so people often ask how a Mishkan long gone can be relevant to our daily life in the 21st Century.

Well, we believe that the Torah is eternal and that God is omnipresent and omniscient, so we must seek those lessons. Here is my list:

Generosity and Wisdom

There are two qualities required of the builders of the Mishkan – generous heart and wise heart. That teaches us that we must give wisely and in a constructive way.

Symbolic Measurements

The measurements of the table, which represents material needs, are in whole units – 2X1 cubits. Those of the ark, which represents spiritual growth, are in half units – 2.5X1.5. That teaches us that we should feel that all of our material needs are met, while always aspiring to complete what is missing spiritually.

Genuine Character Traits

The Torah emphasized several times that the Menorah should be made of one chunk of gold. The adornments were not melded but rather carved out from the body of the Menorah. The adornments represent our character traits. We talk of personality in terms of light and darkness: this person shines, they glow, a guiding light, a bright star, dark thoughts etc. The Menorah encourages us to have our own light and shining qualities traits. They cannot be artificial or superficial, glued to us from the outside. We cannot pretend to have them. We must genuinely acquire them and make them part of us.

Mishkan and Home

The Mishkan resembles a home. It has a light and a table, and in its center, there is the Holy of Holies. In the Holy of Holies, the Torah is found. The message is that our home is our sanctuary. Sanctity is created through daily acts of loving kindness, hospitality, mutual respect, and unity. The center of Jewish life is the home, and at its center the Torah is found, the Torah as a guide for life.

Mishkan and Paradise

The Mishkan also resembles the Garden of Eden. In both of them we can find the Cherubim protecting the Tree of Life. The Torah describes the placement of the Cherubim in Gan Eden with verb שכן – of the same root as the word משכן – Mishkan. Adam lived in the Garden of Eden, and the poles of the Mishkan were held together by a peg called Adan. The Mishkan has its own serpent, just like the Garden. The bolts holding the poles together are called Bariah, a biblical synonym for the serpent. If the Mishkan resembles both Gan Eden and our home, it means that we can turn our home not only into a sanctuary, but into a paradise.

Beware of OCD

The many details of the Mishkan also come to satisfy our need for detailed and quantified rituals. Only the mitzvot related to the Mishkan are so detailed. That includes the number and age of sacrificial animals and the quantity of liquids libated on the altar for each sacrifice. By contrast, the everyday laws are much more general and fluid. That Shows us that we must be careful not to turn our spiritual life into a succession of obsessive-compulsive acts. Religion easily lends itself to OCD, especially with acts such as chanting, counting, and cleansing. There is a special term for religious OCD – scrupulosity. Since in ancient Israel people did not have many opportunities to visit the Mishkan, they learned to live a more flexible religious life most of the year. But now things are different. In my years as a pulpit rabbi, I met many people who would recite every word in the siddur and shake the Lulav with the accuracy of a Swiss watch but did not apply that scrupulosity to their relationships with family and friends.

Coat of Faith

In ancient times, cutting a corner of a garment meant casting doubt on the authority and integrity of the wearer. People in high positions, such as kings and prophets, tended to wear tight clothes to prevent such attacks. By contrast, the High Priest wears an extravagant coat with colorful fringes which even have bells on them. The High Priest was the only one, beside Moshe, who was allowed to enter the Holy of Holies. That was where Moshe would receive his prophecy, and so the colorful and vocal coat of Aharon is a declaration of faith in Moshe’s prophecy.

The Torah says that the coat will never be torn, meaning that no one can cast doubt on the prophecy. The terms it uses to describe the coat’s seam are the same used to refer to language and mouth, hinting at the prophecy which is delivered by words coming out of the prophet’s mouth. Though all those things are gone today, we have the Tallit we wear during prayers. The fringes of the Tallit, which some dye with royal purple, are a declaration that we believe in the veracity of the Torah.

Introvert and Extrovert

The fringes of the coat were decorated with a pattern of a golden bell and a wool pomegranate. The purpose of the bells was to make Aharon’s voice sound when he comes to the Holy of Holies. I would like to suggest that those two adornments represent the personalities of Moshe and Aharon, the only two people who were allowed to visit the Holy of Holies. The bell is highly visible, and it announces its existence and arrival. Similarly, Aharon’s service is clearly displayed on the outside. He wears magnificent clothes and performs the rituals in the Temple for all to see. He also has an outgoing personality and tries to please all. Moshe is like the pomegranate, whose true beauty and value lie inside. Moshe communicates with God and no one else can hear him. His tent is outside the camp and when his face glows with divine light, he covers it with a mask.

When Aharon comes into the Holy of Holies, his voice, or that of his bells, is heard. When Moshe comes into that holy place, he hears a voice talking to him, and he is the only one who can hear it. The adornments of the High Priest’s coat represent those two personalities. They are displayed in a pattern – a bell and a pomegranate, a bell and a pomegranate. This comes to tell us that we should maintain a certain balance of those two qualities. Aharon’s outgoing personality led him to compromise with the people when they wanted to worship idols because he did not want to confront them. Moshe’s tendency to keep everything locked inside caused him to explode in anger several times. We should strive to apply the right approach to our spiritual life and relationships, and to know when to keep it in and when to let it out.

Heavenly Equality

In the first chapter of Bereshit, we read about the simultaneous creation of man and woman. In the second chapter, the woman is created from Adam’s rib as an afterthought. R. Aryeh Kaplan explains that the first chapter is the ideal world of God, a world that never existed, and in which men and women are equal. The second chapter is man’s world, in which there is discrimination and inequality. The increasing awareness of that discrimination and the movement towards changing it are a sign of the coming of Mashiah and return to the Garden of Eden, says R. Kaplan.

During the construction of the Mishkan, which was a replica of Gan Eden, there was a rare moment of equality. The men and the women came together to bring their contribution, and as a matter of fact, the women came first. The women were also among the artisans who created the Mishkan. They are called wise women and women whose heart raised them above the rest with wisdom. The women wove the curtains for the Mishkan. Weaving is an art associated with creativity, creation, language, and storytelling, and was traditionally entrusted to women. The message to us is to continue building our contemporary Mishkan and Gan Eden by working towards the equality of the first chapter of Bereshit.

Questions for Kids: Parashat Pekudei

- When Moshe puts the curtains together, the Torah uses these words to describe it: וַיְחַבֵּר, מַחְבֶּרֶת, חִבֵּר. What is the root of these words?

- What do we learn from this root?

- The cover of the Ark was called כַּפֹּרֶת. On top of the כַּפֹּרֶת there were two ________ .

- What was special about them?

- What does this teach us?

- When מֹשֶׁה saw the beautiful work that בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל did for the Mishkan, what did he do?

- On which day was the building of the Mishkan completed?

- מֹשֶׁה was in charge of building the Mishkan. What happened when he finished putting it together?

- What do we learn from this?

Answers to Questions for Kids

- The root is חבר, which also means friend.

- That to have קְדֻשָּׁה in the Mishkan we must be friends.

- Cherubim – angels.

- They were facing one another.

- That we should always care about one another.

- He blessed them.

- On Rosh Hodesh Nissan.

- He was not able to go inside because it was filled with holiness.

- That when we come together, like the parts of the Mishkan, we create something which has holiness.