The famous story about twelve men, sent on a reconnaissance mission to the Land of Canaan, has two contradicting versions in the Torah.

According to the first version, in this week’s Parasha, God initiated the mission, while according to the second, in Deut. 1:19-46, the Israelites requested it.

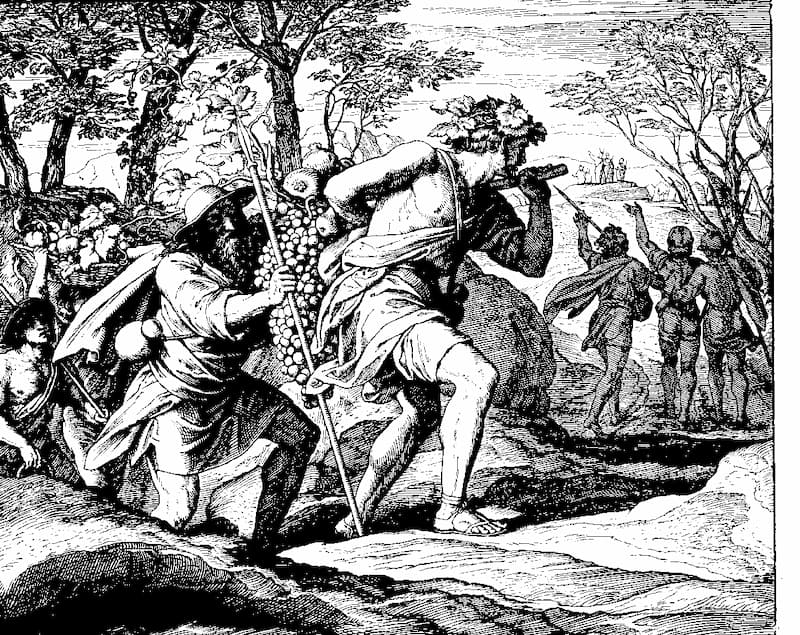

In the first version the men are called scouts and they are asked to gather technical data such as the size of the cities and the nature of the people, whereas the second version have the men described as spies, and their mission is to determine the best route for attack and to identify the first targets.

The most striking difference, however, is the report the twelve men delivered. The scouts of our Parasha deliver an 84-word scathing description of the Land of Canaan. It is a land of great abundance, they say, but it is populated by fierce giants. The land consumes its inhabitants, according to the scouts, and any attempt to conquer it will end in total failure. In contrast, the spies of Deuteronomy return with a succinct and positive report, only seven words long:

טובה הארץ אשר ה’ אלקינו נותן לנו– the land which our God gives us is good.

Yet despite the positive report of the spies, the Israelites erupt against Moshe and God in rebellious contempt and refuse to proceed with the Divine plan.

Here we have to ask two questions: a) why the discrepancy between the two versions? b) why did the Israelites refuse to go to the Promised Land?

I believe that the Torah teaches us that because of the subjectivity in storytelling, one cannot figure out the whole picture unless he listens to different versions of the same event. In this case it is God’s version and Moshe’s version of what has happened.

In Parashat Shelah God speaks of a symbolic mission gone awry. The men were scouts and not spies. They were asked to collect data and not to plan a military campaign. They came back with a long report which stated that it is impossible to conquer the Land of Canaan and its fearsome inhabitants.

In Deuteronomy we hear Moshe speaking. He tells the Israelites that they requested the mission, even though it was God who commanded him to send the men, because he understood that the command was a result of the people’s restlessness. God responded to a message from the Israelites, and granted them a symbolic mission, just to appease them.

God and Moshe viewed the men as scouts sent to gather general information, while the Israelites considered them spies. In Parashat Shelah the reason for the rebellion of the people seems to be the report of the scouts, but in Deuteronomy Moshe reveals the truth. The Israelites made up their mind long before the scouts left. They were not going to go to Canaan, no matter what. The mission was just a pretext and that is why Moshe writes that the report was positive. The reaction of the Israelites had nothing to do with the content of the report.

To prove that this is the message of the contradicting narratives, I would like to travel back in time, to the first rebellious act in the book of Numbers. This act took place immediately after the first successful travel of the Israelite camp, at the end of the tenth chapter of the book. The culmination of the perfect hierarchical plan displayed in the beginning of Numbers was this one voyage, where Moshe invokes God’s might with the beautiful verse we until today read as we open the ark:

ויהי בנסוע הארון ויאמר משה קומה ה’ ויפוצו אויביך וינוסו משנאיך מפניך

As the ark traveled Moshe said: Rise, God, and let your enemies be scattered from before You.

Immediately after that proclamation we read that the people were complaining, but the Torah does not tell us what they were complaining about. Simply – ויהי העם כמתאוננים רע – they were complaining: it is bad.

There was no specific complaint but rather a feeling of restlessness and discomfort, and that is where we can use an analogy to children. A child who cannot yet express himself will cry when feeling uncomfortable. The parents worry in the beginning and try to satisfy the child’s needs, but at a certain point they might become frustrated and feel that the child is doing it deliberately. Experts will tell them, though, that if the child cries it is for a good reason.

Similarly, the Israelites did not know why they felt that way, and only as events unfolded the true reason became clear. They were afraid of going to Canaan and becoming masters of their destiny. Subconsciously they craved the familiarity of Egypt and preferred its relative security over the dream of independent life in a new land.

This stirred them to restlessness and to request, directly or indirectly, that scouts will be sent to Canaan. They perceived those men as spies and could only hear in their report the data which will support a decision to return to Egypt, where they had suffered immensely for generations, enslaved and tortured. They might have considered that the land they want to return to is not the one they know, since it has been ravished by the Ten Plagues, including the hail and locusts which destroyed the agrarian infrastructure. They also could have contemplated the possibility that the Egyptian population, who has been decimated by the plagues and the great losses suffered at the Sea of Reeds, will be less than welcoming to the Israelites, the source of all their trouble.

But all that did not matter, because centuries of enslavement have eroded the decision making process of the Israelites, their belief in themselves, and the understanding that they must take control of their lives.

Not only were they, in the words of Stevie Wonder, “spending most of their lives living in a pastime paradise”, but they were frozen in a childish, immature reality, where they must do as they are told and have no free will.

This is illustrated by Moshe’s words in Deuteronomy. He first rebukes the people who cannot show gratitude to God who “carried them through the desert as a father carries his son”, indicating that they are not willing to “grow up”. He then conjures the imagery of paradise and the Tree of knowledge by saying that not the rebels but their children will inherit the land, the children “who today cannot distinguish between good and evil.”

The Tree of Knowledge is the blueprint of coming of age. A child who defies his parents for the first time is Adam eating of the forbidden fruit. They both realize that they have the power to disobey and that they can use that power for good or for evil.

Alas, with great power comes great responsibility, and the child is not ready for it yet. He constantly tests the boundaries and tries to figure out how to balance power and responsibility. For the Israelites that ability was impaired because they grew up in Egypt as slaves and never had the opportunity to exercise free will.

In the book of Deuteronomy, when Moshe analyzes events in retrospect, he identifies the problem. He tells the Israelites that their behavior was immature and that they wanted to escape reality and live in the land of nostalgia. Only your children, he says, who today cannot distinguish between good and evil, will be able to conquer the land.

Moshe is saying that those children lack the power of distinction today, but they will acquire it later, as they grow up independently. Then they will be ready to use their powers and take responsibility for their lives and actions.

To conclude, the story of the scouts and their failed mission, as told in this week’s Parasha, is a cautionary tale. We sometimes must make life-changing decisions, and we tend, just like the Israelites, to choose the past over the future. The pain, suffering, and difficulties of the past are familiar, we tell ourselves, so we would rather deal with them then adjust to a new reality with its many unknowns.

Almost all decisions, from hip replacement to keeping or breaking a marriage, fit this model, but the difficulty to reach a conclusion fluctuates according to the level of risk involved in the change, the investment we have in our previous lifestyle or conditions, and many other variables.

By telling the story in two different versions, however, the Torah provides us with additional insights.

We should try to learn the whole story, from the point of view of all protagonists.

We can sometimes fully understand events only in hindsight.

Taking responsibility is a gradual process which can be impaired under a totalitarian regime or a disciplinarian parent.

May God guide us in making the right decisions, ones we will be proud to claim responsibility for.

Shabbat Shalom

Rabbi Haim Ovadia

Ohr HaChaim Yomi – Emor