Mishkan and Home

What can the Mishkan be analogized to? When I present this question at a class, the first, intuitive answer, is that the Mishkan resembles a home, and the second, which comes after a minute of contemplation, is the Garden of Eden. Like a home, the Mishkan has a table, a candelabra, a place for preparing food, and private chambers. The word Mishkan is derived from the root שכנ, to dwell, which is also the root of the Hebrew word for a personal dwelling. This connection is evident in Balaam’s praise of the Israelites (num. 24:5):

מה טובו אהליך יעקב משכנותיך ישראל

How beautiful are the tents of Yaakov and the dwellings of Israel!

Balaam was speaking of the personal tents of the Israelites, but the double entendre did not escape the commentators. This is how Targum Yerushalmi translates it to Aramaic:

מַה טָבִין הִינוּן מַשְׁכְּנִין דְצַלִי בְהוֹן יַעֲקֹב אֲבוּהוֹן וּמַשְׁכַּן זִמְנָא דַעֲבַדְתּוּן לִשְׁמִי וּמַשְׁכְּנֵיכוֹן חֲזוֹר חֲזוֹר לְכוֹן דְבֵית יִשְׂרָאֵל

How good are the tents where Yaakov prayed, the Mishkan of Gathering you made in honor of My Name, and your tents which surrounded it, oh House of Israel.

The Targum uses the analogy of the Mishkan and the home, the Divine and the individual dwelling, and connects the personal tent to the Mishkan and the synagogue. Because of that special connection, Rav Amram Gaon writes in his Siddur that we should recite this verse when we enter the synagogue. In some communities, this verse is also chanted as an introduction to the wedding ceremony. This symbolizes the sanctity with which the bride and groom are going to imbue their new home.

Home is Mishkan

Most people understand this resemblance as suggesting that our homes should emulate the Mishkan, but Nahmanides offers an opposite energy flow. In his introduction to Shemot, he explains that the life of Israel in Egypt and the desert replay the life of the forefathers on a grander scale. Genesis is the Book of Individuals, while Exodus is the Book of the Nation. In Genesis, Avraham seeks refuge in Egypt because of the famine, his wife is captured by Pharaoh, who is punished with plagues, and who then sends Avraham and Sarah free with great riches.

Does this summary sound familiar? Of course! It is the trajectory of the journey of the Israelites. They went down to Egypt because of the famine, they were captured by Pharaoh who was punished with plagues, and who then sent the Israelites free with great riches.

But wait, there’s more. The Israelites, as a nation, had to follow in the footsteps of their forefathers until reaching perfection. Writes Nahmanides:

הגלות איננו נשלם עד יום שובם אל מקומם ואל מעלת אבותם ישובו… וכשבאו אל הר סיני ועשו המשכן, ושב הקדוש ברוך הוא והשרה שכינתו ביניהם, אז שבו אל מעלות אבותם שהיה סוד אלוה עלי אהליהם, והם הם המרכבה, ואז נחשבו גאולים. ולכן נשלם הספר הזה בהשלימו ענין המשכן ובהיות כבוד ה’ מלא אותו תמיד

The exile is not over until they reclaim their place, at the same level of their forefathers… when they came to Mount Sinai, and built the Mishkan, the Divine Providence dwelt among them. Then they returned to the level of their forefathers, in whose tents God was present, and who themselves were the Divine Throne. With that, the Israelites were fully redeemed and that is why this book concludes with the construction of the Mishkan and with the constant presence of God in it.

Note that Nahmanides doesn’t say that our homes emulate the Mishkan but rather that the Mishkan is a replica of the home. He says that only when the Israelites built the Mishkan they achieved the spiritual level the forefathers had at their homes.

Portable Mishkan Gives Hope

This is a very powerful message. The Jews who were exiled from Spain after living there close to a thousand years, and who lost their homes and their synagogues, could find hope and encouragement in Nahmanides. His words were also comforting to his contemporaries, who longed to the rebuilding of the Temple and who were already suffering under Christian persecution. This message is also empowering and uplifting for modern-day Jews, and as a matter of fact, all people.

Religious life today revolves around the synagogue, the mini-Mishkan. If there is no synagogue in your vicinity, or if you are not a regular visitor to the synagogue, your religious life is considered, by you or by others, as incomplete. Even if you have a synagogue nearby and you visit it regularly, the Temple of Jerusalem is still missing from your life. But the eye-opening interpretation of Nahmanides tells us that we may pray and wish for the reconstruction of the Temple, and we may be prompted to go to synagogue, but the real temple is with us at all times. It is our home, our family.

This interpretation is anchored in the Tanakh and in history. Daily life in ancient Israel did not revolve around the Temple. As an agrarian society, people were working in the fields most of the time and would visit the Temple only three times a year. The real Mishkan was their home, and they were expected to fill it with sanctity. That is why there are so many laws governing the treatment of the land and the crops, our behavior towards others, and the responsibility for the sojourner, the widow, and the orphan. These laws are the daily service. They are meant to transform us into holier people, and our home into a sanctuary, a Mishkan. When we invest our home with sanctity, mutual respect, intimacy, and loving kindness we also, like our forefathers, can become the throne of the divine Shekhina. Adhering to the behavior code and discipline of the Torah helps us elevate ourselves, become better people, and develop a connection with God.

Mishkan and Eden

The Mishkan also takes us to the creation of the world and to Eden. The connection to creation is beautifully presented in Proverbs (3:19-20), a book which in some ways is a commentary on Genesis:

יְיָ בְּחָכְמָ֥ה יָֽסַד־אָ֑רֶץ כּוֹנֵ֥ן שָׁ֝מַ֗יִם בִּתְבוּנָֽה, בְּ֭דַעְתּוֹ תְּהוֹמ֣וֹת נִבְקָ֑עוּ

YHWH through wisdom founded earth, set heavens firm through discernment, through His knowledge the deeps burst open…

The creation of the earth, the heavens, and the abyss, was accomplished by the same character traits used by Bezalel to build the Mishkan (Ex. 35:31):

וַיְמַלֵּ֥א אֹת֖וֹ ר֣וּחַ אֱלֹהִ֑ים בְּחָכְמָ֛ה בִּתְבוּנָ֥ה וּבְדַ֖עַת וּבְכָל־מְלָאכָֽה

He [God] imbued him [Bezalel] with the spirit of God, with wisdom, discernment, and knowledge, and with all crafts.

Bezalel’s qualities, given to him by God, circle back to creation. They are bookended by the Spirit of God, which appears in the opening verses of Genesis (1:2), and the word מלאכה, which is found in the last passage of the story (2:3):

כי בו שבת מכל מלאכתו אשר ברא אלהים לעשות

In it [Shabbat] God ceased all his craft which he created to be made.

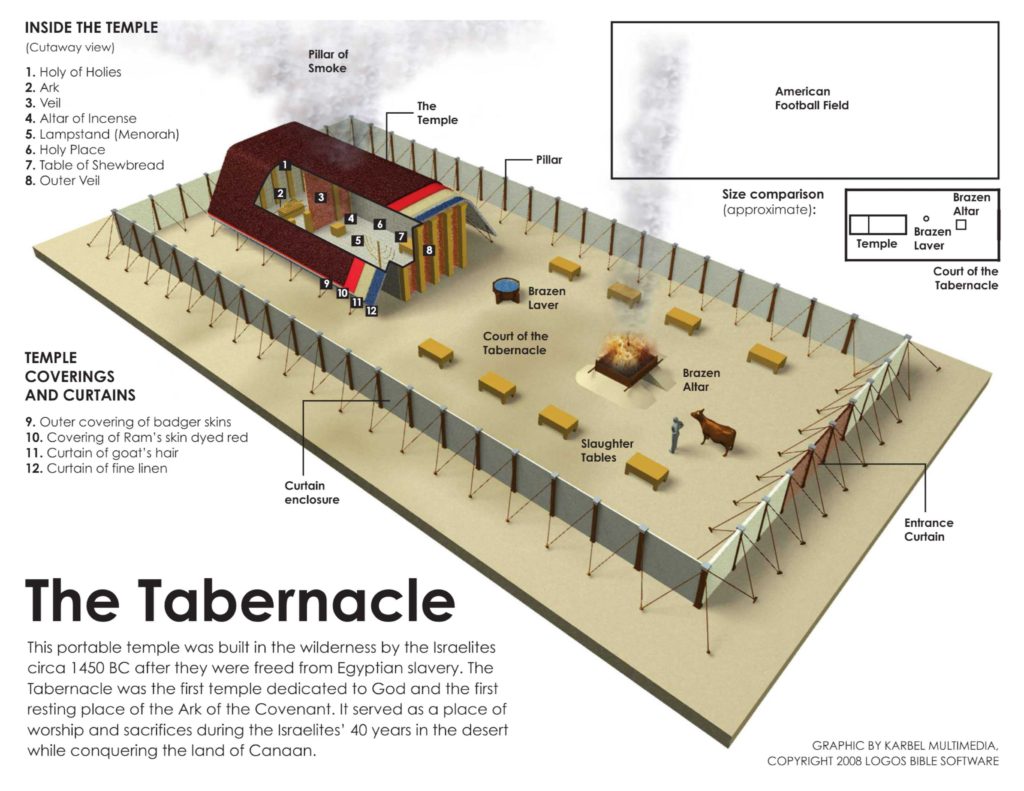

The analogy is not only textual, but also visual as well. Eden was surrounded by four rivers, and the Mishkan by four walls. In Eden lurked the serpent, while within the walls of the Mishkan the central bolt was coiling. The Hebrew word for bolt – בריח, appears twice in the Tanakh is the sense of serpent (Job 26:13, Is. 27:1).

In both Eden and the Mishkan, the remedy for the serpent’s poison is the Tree of Life. We know that the woman and Adam were lured by the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge because it was forbidden. When God places in Eden the Tree of Life guarded by the Cherubim, He is inviting mankind to come and get the fruit. In the Mishkan the Tree of Life, the Torah (see Prov. 3:18), was placed in the Ark and guarded by the Cherubim. The Tree of Life is physically inaccessible in both places, but after the Torah was given to the Israelites on Mount Sinai, it is always available to us. In our darkest moments, when our temples and synagogues were destroyed, when our scrolls of Torah and tefillin were burned, and when our bodies and minds were targeted by our enemies for annihilation, we carried the words and memory of the Torah with us, and wherever we went, we built a Mishkan at home, looking forward to restoring Eden.

The Mishkan is an analogy to the home and to Eden. This triple connection tells us that our home, our family, can become both Eden and a dwelling place, a Mishkan, for the Divine Shekhina. When we place those three on a time-continuum axis, the Mishkan is our past, our home is our present, and Eden is our future. We should remember what we had in the past and aspire to what we can achieve in the future. The vessels of the Mishkan are the table where we eat and the light that shines on our home. The holy Ark can be found in the intimacy of our home, where it holds the Torah, the Tree of Life. With its power we could turn our lives in the present into the Garden of Eden.

Questions for Kids: Parashat Terumah

- What were בני ישראל asked to bring?

- Which three metals were needed?

- What are the special vessels of the Mishkan?

- How were these vessels carried from place to place?

- What was inside the Aron?

- What was on top of the Aron?

- What was put on the Table?

- What is the special instruction regarding the Menorah?

- How many branches were in the Menorah?

- How many wool curtains were in the Mishkan?

- How many curtains made of goas’ skins covered the Mishkan?

- What held together the boards which formed the walls of the Mishkan?

Answer Guide for Parashat Terumah

- A donation of materials to build the Mishkan.

- Gold, silver, and copper.

- The Aron, the Menorah, the Table, and the Altar: ארון, מנורה, שולחן ומזבח

- With rings on their sides and poles through the rings.

- The Tablets of the Law and the Torah.

- Cherubim – angels.

- A special bread – לחם הפנים

- It must be carved out of one piece of gold.

- Seven.

- Ten.

- Eleven.

- Silver bolts.

Enjoy reading and learning.

More related to Terumah: