Forgotten Piety

Creating Godliness

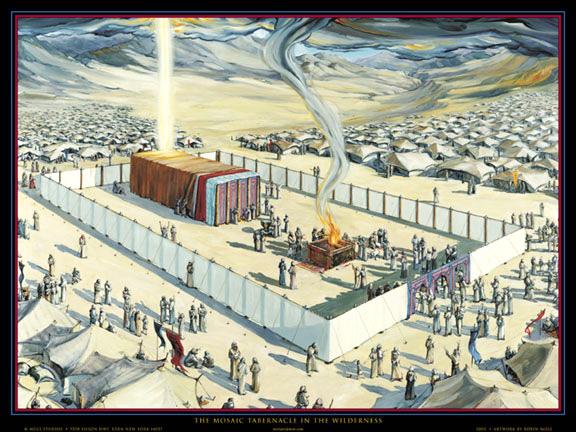

In Parashat Tetzave we read of women and men who were endowed with a divine spirit of wisdom, intelligence, and knowledge. Those men and women were responsible for the creative craftsmanship and the detailed construction of the Mishkan:

רוח אלקים… בחכמה ובתבונה ובדעת… מלאכת מחשבת

These Hebrew words resonate with our perception of creation, is because the Tankakh uses this terminology to describe the Mishkan and the creation:

In Genesis we find the divine spirit hovering over the abyss at the dawn of creation, before the formation of heaven and earth:

רוח אלקים מרחפת על פני המים

The book of Proverbs[1] describes the Creator’s intellectual tools in the same words used to describe the builders of the Mishkan:

ה’ בחכמה יסד ארץ, כונן שמים בתבונה, בדעתו תהומות נבקעו

God established the earth by wisdom, He founded the heavens by intelligence, by His knowledge the depths burst apart.

What about craftsmanship? When discussing the categories of work forbidden on Shabbat, the Talmud states:[2] מלאכת מחשבת אסרה תורה.

The definition of the work forbidden on Shabbat is derived from the type of work involved in the construction of the Mishkan. Since the Shabbat itself is a reminder that the world was created by God, who rested on the seventh day, the equation is complete: God ceased craftsmanship on the seventh day, and so did the builders of the Mishkan. During the other six days, both Creator and craftsmen were engaged in the same type of activity – creation through wisdom, intelligence, and knowledge.

The Torah gives us a detailed account of the construction of the Mishkan. It tells us of the spinsters, weavers, carpenters, jewelers, and goldsmiths. The Torah teaches us that creativity is the essence of the Image of God. Just as the whole creation speaks of the might and wisdom of the Creator, so does every creative insight of human beings. We craft words, threads, or stones, we invent gizmos and apps, we tame nuclear power and decipher the secrets of the DNA. We can do all these because we emulate God. Our creative, inventive, and inquisitive minds mirror Our Creator.

Parashat Tetzaveh – Weaving, Language, Creation

A beautiful Midrash[3] compares the creation of the universe to an ongoing act of weaving by God, from two spools, one of fire and one of snow, which keep expanding on an infinite loom:

כיצד ברא הקדוש ברוך הוא את עולמו? אמר רבי יוחנן, נטל הקדוש ברוך הוא שתי פקעיות, אחת של אש ואחת של שלג, ופתכן זה בזה ומהן נברא העולם

Another Midrash explains that the creation of mankind culminated with the gift of language. Modern science concurs with that statement, albeit in a somewhat different phrasing:

Language created Homo sapiens![4]

The two Midrashim artfully entwine and interweave the concepts of creation and language with those of creativity and weaving. They convey the message that the ability to use our verbal skills correctly is a form of art. Just as the seemingly meaningless threads join in the hand of a master weaver to display patterns, images, and stories, so the human mind fabricates language by weaving letters to words and words to sentences.

A.S. Byatt writes[5]:

We think of our lives, and of stories, as spun threads, extended and knitted or interwoven with others into the fabric of communities, or history, or texts… words that connect weaving with storytelling: text, texture, and textile, the fabric of society. Words for disintegration – fraying, frazzling, unraveling, woolgathering, loose ends. A storyteller or a listener can lose the thread… The processes of cloth-making are knitted and knotted into our brains, though our houses no longer have spindles or looms.

The metaphors and connotations of language, garment making, and creativity, are usually positive. For example, the clothes God made for Adam and his wife (Gen. 3:1) and grandma’s hand-knitted sweaters. The famous TED conferences explore Technology, Education, and Design, or in other words: inventiveness, language, and creativity. On the negative side, the Hebrew word for clothes is derived from the same root as treason, because one uses clothes to disguise his true nature. Throughout history deception, promiscuity, and witchcraft, were associated with women engaged in weaving or spinning yarn. In the 16th century, King Louis XIII of France banned the making of lace.

The fear and resentment of the craft stemmed from the Immense power of creativity, a power which cannot be contained or controlled. Creativity is a manifestation of the free spirit of mankind and of the uniqueness of each human being. Tyrannical and oppressive regimes sought therefore to eliminate or control linguistic, as well as artistic, creativity.

In contrast, the description of the Mishkan speaks volumes of the importance of creativity and of harnessing our talents to the advancement of spirituality, which is also expressed by the aesthetic experience. The Torah delegates the most sacred role, the creation of the fabrics which will envelop and protect the holy Mishkan, which invites the Divine Providence to dwell among humans, to the wise women. Those women spun and wove the magnificent yarns into beautiful curtains of blue, royal purple, crimson, and white.

Bring Back the Tinkerers

Alongside the women, the undisputed stars of the 450 verses dealing with the fabrication and construction of the Mishkan are the artisans. The names of those artisans are symbolic. Betzalel ben Uri is under God’s wings, and he is the son of light. The name of his colleague, Aholiav ben Ahisamakh, means supporter and companion, the one who dwells at the father’s tent. These men led a team of creative designers, tinkerers, and craftsmen, who emulated God’s creation by using their God given talents.

The Torah encouraged creativity, which in ancient times was nurtured by apprenticeship and hands-on experience, but we have forgotten that. The sad reality of modern society is that most schools lack any serious program or incentive for young minds to develop such skills, not just in elementary and high schools, but in higher education institutions as well.

Several years ago NASA recruited many new young engineers, but found out that those graduates of the leading schools in the country were incapable of solving problems. A comprehensive study comparing the problem solvers with the non-solvers found that the problem solvers used to tinker and work with their fingers as kids. Whereas the problem solvers triggered many areas of their brains and established a line of communication between the abstract and the physical world, the extremely sophisticated knowledge digested by the theoretical engineers was two-dimensional. That knowledge was ethereal and impractical, based on books alone and not fully engaging the tremendously flexible power of the human brain, which has not one, but many possible solutions to any given problem as author David Eagleman explains in his book Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain.

Tinkering Jobs

One of the most influential tinkerers of our times is Steve Jobs. Jobs whose adoptive father was a mechanic, used to first take apart appliances and then cars. He admired the beauty and elegance which go beyond the utilitarian purpose of an object, and eventually became the man who has revolutionized four industries with his ability to combine practicality, creativity, and aesthetics.

In his book Free to Learn, Peter Gray describes the Sudbury Valley School, the visionary school founded in the late 60’s by Daniel Greenberg. In this free school, students ages 4-19 have free access at all times to workshops and materials of all kinds. This approach has allowed thousands of students to develop their skills and artistic talents and provided them not only with a solid profession but also with joie de vivre and peace of mind. One of them, Tom, speaks of his experience at the school (pp. 107-109):

I was in sixth grade, and I was doing anything I could do to rebel against the system… [in] Sudbury Valley there was nothing to rebel against… so we just played…

Tom fell in love with the Plasticine workshop where he would work with a friend from morning till night, making models of towns with hotels and saloons, vehicles, factories, people, tanks and weapons. Today he is a master machinist and inventor of high-tech industrial machines.

The state of creative education, especially in our Jewish schools, makes one wonder, if God would have commanded us to build the Mishkan today, would we be capable? Would our kids be capable? Do we nurture and encourage the natural artistic talents with which God blessed us or do we limit and force our knowledge and learning style into set frames and boundaries?

The Torah commands us to be creative in any way and form possible because our home is the eternal Mishkan. We should kindle a Divine spark in it, and then build and craft our home, just like the builders of the tabernacle, with wisdom, intelligence, and knowledge. We will then be imbued by the divine spirit and will be ushered in to engage in a thoughtful and life-transforming creativity[6].

Join us for a weekly discussion on the Parasha of the Week. See schedule for full details here.

[1] 3:19-20

[2] Yom Tov 13:2

[3] Bereshit Rabbah 10:3

[4] Martin Nowak, Homo Grammaticus, Natural History, 12/2000, p. 44

[5] The Guardian, 6/20/2008

[6] Suggested reading: The Element, by Sir Ken Robinson; Free to Learn, by Peter Gray; Steve jobs, by Walter Isaacson, pp. 1-85; Incognito: The Secret Lives of Our Brain, by David Eagleman; Spinning Fantasies, by Miriam B. Peskowitz.

Questions for Kids: Parashat Tetzave

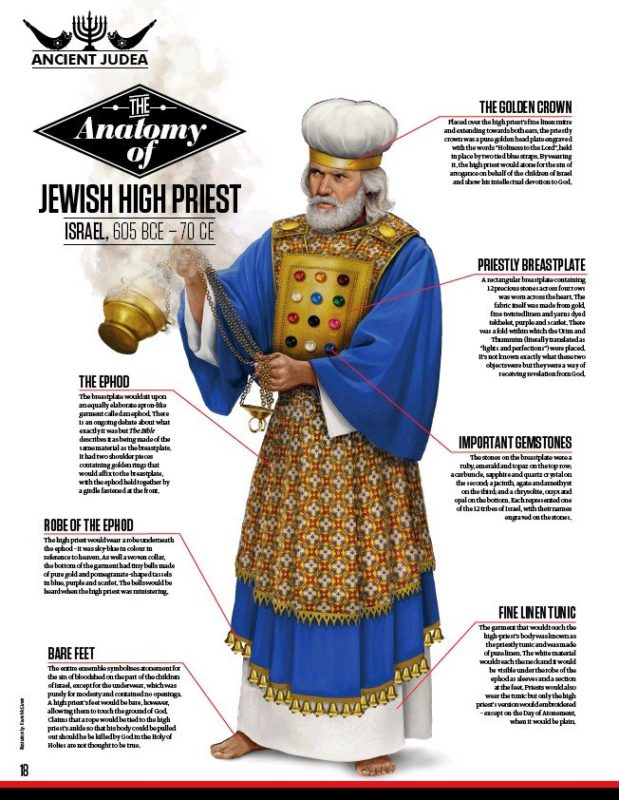

This week we read Parashat Tetzave. Aharon and his four sons – Nadav, Avihu, Elazar and Itamar, were chosen by HaShem to serve as Kohanim. One of their tasks was to keep the lights of the Menorah burning continuously in the Mishkan. While serving in the Mishkan, the Kohanim had to wear special garments.

Aharon, who was the Kohen Gadol, had to wear special garments made by skilled craftsmen, which were different from the garments of the other Kohanim.

1. What is the root word of תְּצַוֶּה?

2. What were בני ישראל commanded to bring? Why?

3. What is the meaning of נר תמיד – Ner Tamid?

4. What were the clothes of the regular Kohanim?

5. What were the special clothes of the Kohen Gadol?

6. Why are the clothes of the Kohen Gadol and regular Kohanim different?

7. Moshe’s name is not mentioned in Parashat Tetzave. What is the reason, according to the Midrash?

Answers to Questions for Kids

1. צוה – to command.

2. Pure olive oil. To light the Menorah.

3. The light that was continuously burning.

4. כְּתֹנֶת, אַבְנֵט, מִכְנָסַיִם, וּמִגְבַּעַת – tunic, belt, pants, and hat.

5. Same four as the regular Kohen, only that his hat was called מִצְנֶפֶת and not מִגְבַּעַת. In addition, he had four more: אֵפוֹד, חֹשֶׁן, מְעִיל וְצִיץ –

Ephod, a sleeveless shirt. On the shoulder straps there were two precious stones with the names of six tribes on each.

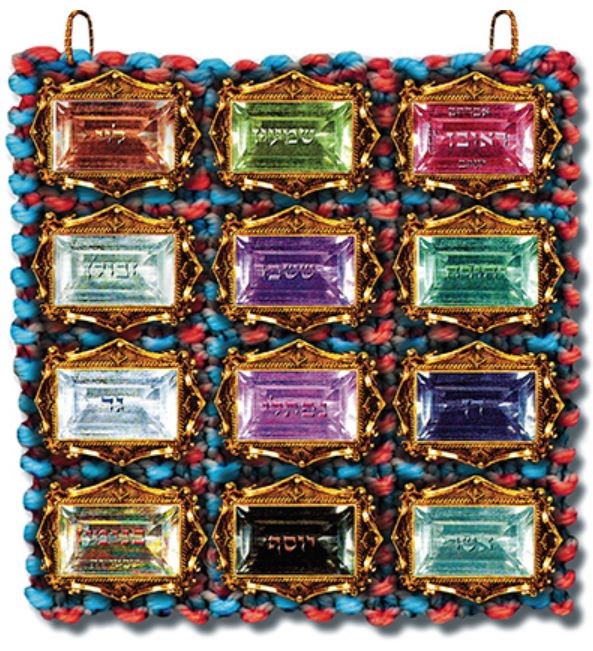

Choshen Mishpat: A small golden plate with twelve precious stones, each with the name of one tribe.

Robe – מעיל: A robe of the color Techelet, decorated with golden pomegranates and bells.

Tzitz: A gold band worn over the forehead, with the words קודש לה’.

6. The robes were לְכָבוֹד וּלְתִפְאָרֶת – for honor and glory. They gave honor to their work of serving in the Mishkan, and the people honored them because of the special robes which marked their position.

7. Because when Moshe prayed to ה’for בני ישראל after they did the golden calf, he said that if ה’ does not forgive the people, Moshe’s name should be erased from the Torah. ה’ forgave the people and omitted Moshe’s name only from on Parasha.

Ohr HaChaim Yomi – Shemini