Choosing a college major is a tricky business. You start studying for the profession most in demand at the moment, just to find out four years later that the world has drastically changed. Programming, or coding, has been one exception and a safe bet for the last couple of decades, but this too is about to change. Deep neural networks are the new frontier, for now being the closest thing to self-learning machines which are going to beat our comparatively stupid computers. We are looking into a future where machines will not depend on a set of commands programmed by humans, but rather on analyzing millions of cases and mountains of data, and finding a way to make their own conclusions. For people in the field, the exciting event heralding that era was Google’s DeepMind beating the world’s best Go player, Lee Sedol. To reach that moment, DeepMind was fed 30 million moves of human players, but the moment of awe and exhilaration came when DeepMind made an original move, never played before. For the first time, humans where watching a machine thinking independently.

Machines are not ready yet to think like humans, though, since there is still the issue of cracking the code of human unpredictability and the endless possibilities of human reactions, emotions, and subliminal messages. One man who knew that the ability to flow with and adapt to the ever-changing circumstances of the human condition was out patriarch Jacob.

Think for a moment of this question: Where did Joseph disappear to, after dominating the last thirteen chapters of the book of Genesis? In the other four books of the Torah the leader and main protagonist is Moshe, of the tribe of Levi. Moshe’s disciple and successor, Joshua, is the only one from among Joseph descendants to become a national leader with a positive image. In the rest of the bible, Menashe and Ephraim appear to have a divisive and cantankerous character, culminating with the massacre of forty-two thousand Ephraimites by Jephthah, of the tribe of Menashe. Later on, Ephraim becomes the main force in the creation of the divisive Northern Kingdom, and is the one tribe singled out and criticized by the prophets active there, most significantly Hosea.

Judah, on the other hand, emerges as the ultimate leader of Israel, the once and future king. After the failed reign of Saul, of the tribe of Benjamin, the history of the Israelites revolves around David and his dynasty, both in history and in the literature of the Davidic dynasty, which includes Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs.

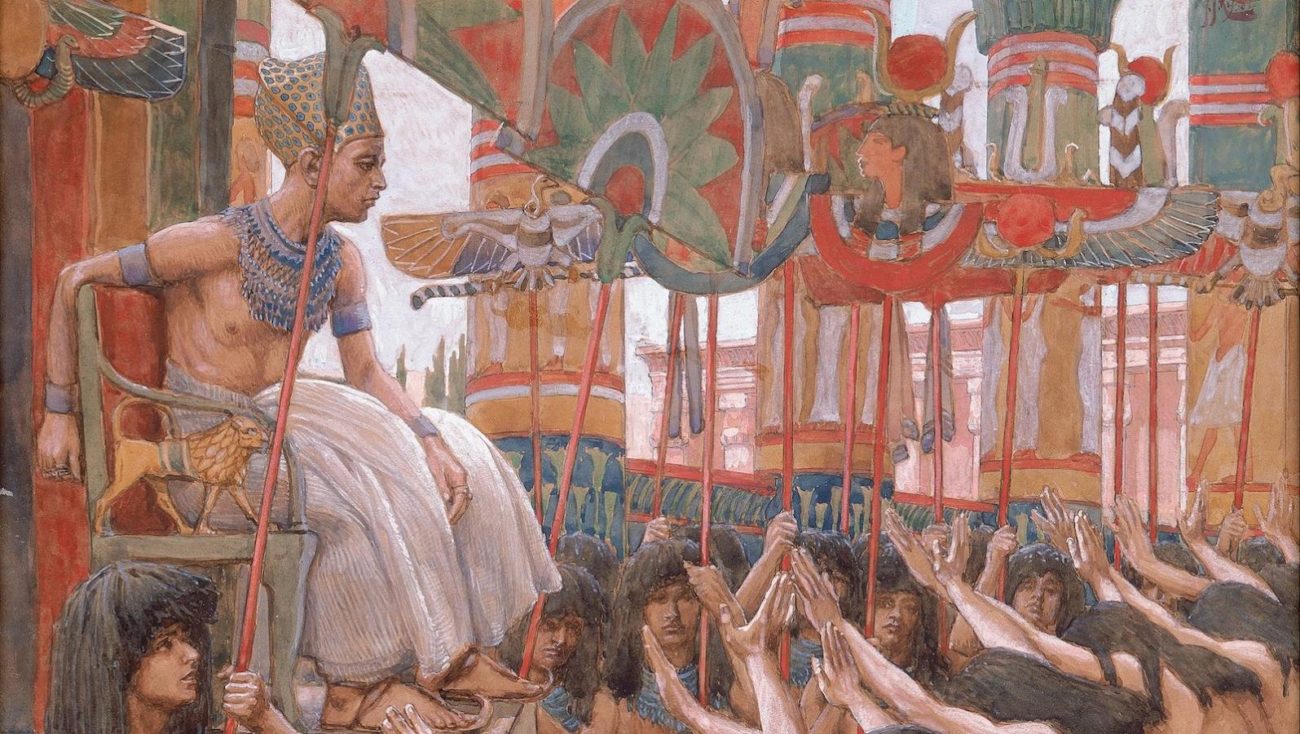

This is most surprising, given Joseph’s stellar performance and achievements as an administrator and viceroy, and his image as one who saved his family from dying in hunger. Let us briefly review what Joseph was able to accomplish single-handedly, relying purely on his intelligence and communication skills. He was able to secure the position of the second-in-command by delivering a brilliant interpretation intertwined with a job application. He convinced the Egyptian farmers to save more wheat by making them believe that distribution during the famine will be local and merit-based, but then shared the crops equally with all Egypt. Joseph accused his brothers of being spies to enable them to refute the accusation and clear their name when they eventually come to Egypt. He managed to squeeze out of Pharaoh a royal decree for the settlement of Jacob’s clan in Egypt without directly asking for it, and he guided his brothers how to speak to Pharaoh in order to be allotted the fertile land of Goshen. He also managed, as representative of the crown, to purchase all Egyptian land, while keeping the sharecroppers happy and thankful. Finally, he convinced Pharaoh to let him bury his father Jacob in Canaan, by insinuating that if he denies his request, there is no guarantee that the king will receive his proper burial and peaceful sailing into the world of the dead. But that glorious past vanishes in the later books of the bible.

The fall from grace of the House of Joseph has its early origins in Jacob’s last will. It is expected that Jacob, who showed his proclivity for preferential treatment and disregard of the natural order of birth, will bypass Reuben and appoint another brother as a successor and future leader, but we would have assumed that brother to be Joseph. But Jacob, despite Joseph’s impressive portfolio and his status as the favorite child of the favorite wife, decides to appoint Judah, and not Joseph, as king, legislator, and future leader of the Israelites. Jacob does give a wonderful blessing to Joseph, describing his travails and hardships, praising him as one who is set apart from his brothers, and promising him abundance, but never referring to him as a leader. What did Jacob see that made him prefer Judah over Joseph as the future leader, despite Joseph’s unprecedented commitment to his father and success as the viceroy of Egypt?

Three words in Judah’s blessing hold the key: מטרף בני עלית – you have risen from devouring my son. These words could be read in two ways: You [Judah] have risen from devouring my son [Joseph]; You have risen from devouring, my son [Judah]. Both have a somewhat similar meaning, but the second conveys Jacob’s understanding and appreciation of Judah’s humanity. Like David after him, Judah is volatile and emotional, he is not immune to sin and irrational moves, but he is able to acknowledge his errors and confronts them. He was actively involved in the disappearance of Joseph, but years later was able to rise above his jealousy and fervently defend his father’s other favorite child, Benjamin. He fell prey to his desire when enticed by Tamar, but was able to admit his mistake and publicly announce: צדקה ממני – she is righteous and I am a sinner.

Jacob’s message is that there is no perfect human being and therefore no perfect ruler. With all the elegance and intelligence of Joseph’s calculated moves, played out like those of a true Chess Grandmaster, they did not take into account human sensitivities and emotions. On his path to fulfil the goal of saving his clan during the famine, and for the sake of the greater good, Joseph caused unnecessary pain to his father and brothers, among whom was the innocent Benjamin. His behavior at his father’s funeral made the brothers think that he is going to cause them harm, and in general he was so busy with running the kingdom, that he had no time left for family. That is, I believe, one of the reasons Jacob asks him, when he comes with Menashe and Ephraim. “who are these?” as if saying “I don’t see you anymore!”.

Joseph truly believed in what he was doing, and suppressed his own emotions to achieve his goal, but Jacob eventually taught him, and us, that life is not a game of chess, and cannot be played by machines.

This unexpected ending of the saga of the House of Jacob teaches us an important lesson about maintaining a balance between the greater good, whether religious or national, and the immediate needs, sensitivities, and feelings of those surrounding us.

Ref:

1. For those readers who would like to delve further into the story, here is the full analysis of Joseph’s success in convincing Pharaoh to bury Jacob in Canaan: When Jacob makes his request, he says (49:29-30): קברו אותי את אבותי אל המערה אשר בשדה עפרון החתי… אשר קנה אברהם את השדה – Bury me with my ancestors at the cave in the field of Ephron the Hittite… the field which Abraham purchased…

Jacob wished to be buried in Canaan, and even though this request is directed to all his children, he already prearranged with Joseph to be in charge of assuring it so happens (47:29-31). Jacob knows that Joseph is the only one who will be able to arrange for the burial at Canaan, and Joseph indeed takes no chances as he approaches Pharaoh, taking into account the possibility that the monarch will refuse, either because he needs Joseph’s services and does not want him to defect, or because he respects Jacob and wants him to be buried in Egypt.

In either case, for Joseph failure is never an option, so he carefully phrases his request (50:4-5): וידבר יוסף אל בית פרעה לאמר, אם נא מצאתי חן בעיניכם דברו נא באזני פרעה לאמר: אבי השביעני לאמר, הנה אנכי מת, בקברי אשר כריתי לי בארץ כנען שמה תקברני – Joseph’s spoke to Pharaoh’s courtiers, saying, if you favor me please speak to Pharaoh and tell him on my behalf: my father made me take an oath, saying, I am about to die, in my grave which I have dug at the land of Canaan, there you shall bury me.

There are two problems with these verses: a) The method of delivery seems cumbersome – why doesn’t Joseph address Pharaoh directly? b) Why is Joseph saying that Jacob dug the grave?

The answer lies with the burial culture of ancient Egypt. Egyptian monarchs invested a lot of thought and resources in securing their eternal place in the World of the Dead. They built magnificent structure, the pyramids, whose sole purpose was to serve as mausoleums, and created sophisticated methods to protect them from tomb-raiders. But with all their power and prowess, the kings and queens always had one weak link in the whole system – loyalty. Who would assure them that following their death they will be treated properly and buried according to their specifications? The only way to assure that this will happen was to surround themselves with loyal servants. Joseph is well aware of the problem and he takes full advantage of it with subtle shrewdness.

Instead of approaching the king directly and discretely, he sent the request through the royal courtiers, practically releasing it to the media. In doing so he made it harder for Pharaoh to refuse now that so many people are aware of the request, since refusing Joseph’s request might cost him his servants’ loyalty. Joseph also paraphrased Jacob’s words. Instead of speaking of a purchased grave, he uses the word כָּרִיתִי – I dug, making an allusion to the Pyramids which were usually constructed by order of the king and under his watchful eye. While Pharaoh might have still been able to refuse Jacob’s request to be buried in a purchased grave without losing his servants’ trust, because he could have claimed that the real “Mitzvah” is to be buried in a grave you made yourself, he cannot make the same argument regarding a grave which Jacob dug with his own two hands. So was Joseph lying? Not at all! He merely exchanged the verb קנה – to purchase, with the verb כָּרָה which has two meanings: the more common one is “to dig”, and the other, less frequent, is “to purchase” (see Deut. 2:6 and more indisputably in Hos. 3:2). Joseph has only reiterated his father’s request, but Pharaoh understood that Jacob personally prepared the grave and had therefore no option but to acquiesce.