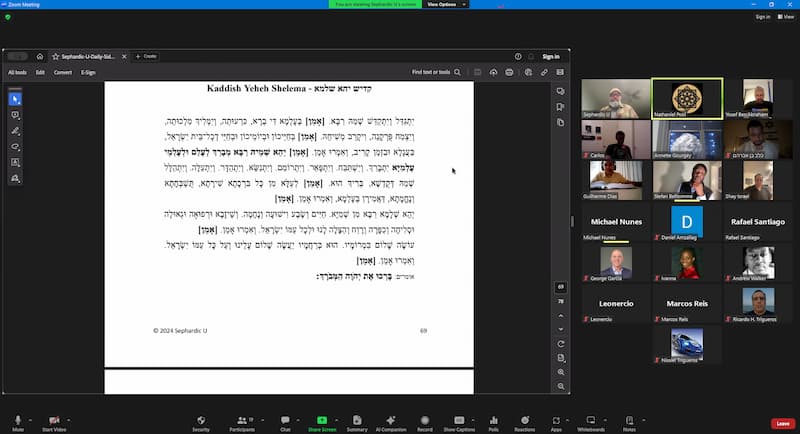

A day without Kaddish

I have received many questions about Kaddish; here are some of the most common:

What should I do if I cannot find Minyan for Kaddish while traveling?

What if I live in a place where there is no regular Minyan?

- I do not feel inspired by Kaddish and I do not see the connection between its words and my grief, but I feel guilty if I do not say it?

- Should I pay someone to say Kaddish for my loved ones?

A: It is true that the text of the Kaddish has nothing to do with grief and mourning. Originally, the Kaddish was a prayer recited at the end of a learning session. It is that context that the Sages said that the world is sustained by the merit of the Kaddish. They referred to the spiritual gain achieved by attending classes, which enhance the listeners’ knowledge and inspire them to improve their behavior.

Later on, the Kaddish was incorporated into the public prayer services, and at a certain point it was designated for the mourners, some of whom did not understand the Hebrew prayer and were comforted by reciting a prayer in Aramaic, their spoken language. Ironically, many of today’s mourners who come to shul only for Kaddish understand neither the Hebrew nor the Aramaic. However, they do find comfort in having a role in prayers and in believing that the Kaddish is a source of spiritual joy for their loved ones who passed away.

Throughout the ages, religious leaders understood that the Kaddish empowers and soothes the mourners, and in some communities they encouraged them to say more Kaddishim during the prayers, so they will feel included. Thus the Kaddish has been infused with a new meaning which transcends its original text. It has become for many Jews a symbol of continuity, respect for one’s parents, a declaration of faith, a feeling of inclusion in the community, and a way for the rabbis to connect to people who were otherwise alienated from an observant lifestyle.

In addition, it is taught that the Kaddish elevates the soul of the deceased. The original meaning of that statement was not that the Kaddish has some mystical power to change the inner workings of the afterlife, but rather that the behavior of the surviving relatives is a testament to the influence of the deceased ones on them. Therefore, it was considered especially important to say Kaddish for one’s parents, since it showed that the child respects the parents and that he or she were properly educated. It is obvious that in this context the Kaddish is the means, not the goal. The goal is to be a better individual and to attribute the improvement in one’s character and lifestyle to the influence of the parents on him and to the respect he feels towards them. The next logical step would be to understand that any good deed performed in honor of our loved ones who passed away is a source of spiritual joy for their souls. It is also understood that if one hires someone to say the Kaddish while his life remains unchanged, he is not showing any respect or grief.

We can now address the questions presented above. The importance of the Kaddish is for the person saying it. It provides solace, inspiration, and a feeling of fulfilment of his or her duty towards the deceased and the community.

If one is traveling or unable to say the Kaddish for other reasons, he could substitute the Kaddish with additional good deeds: give charity, offer emotional support to someone in need, treat people around him with greater care and respect, read some psalms. The same follows for a person who is not inspired by the Kaddish. Instead of feeling guilty, that person should immerse himself in acts of kindness and philanthropy and have in mind that he is doing it honor and memory of his loved ones.

Regarding the practice of reciting of Kaddish by a paid person, it started as an act of charity, and was a way for the mourners to support people they knew personally. Today, unfortunately, this practice has become a faceless, emotionless industry, with dedicated websites. If you feel that you still want someone to cover for the days or months when you cannot recite the Kaddish, I recommend one of the following:

Ask a good friend, who is anyway saying Kaddish, to have your relative’s name in mind; ask someone you know personally and who is needy to do it for a fee; Turn to an institution which you find important, an orphanage, for example, and which offers Kaddish reciting services.

Finally, conforming to the societal norms or one’s consciousness is a personal issue, so my words here are a recommendation and an attempt to explain the meaning and place of Kaddish in our lives. It is also a call on people not to abandon the essential and cling to the marginal. Rabbi Yosef Eliyahu Henkin worded it beautifully:

“Instead of reciting endless Kaddishim, one should learn more and give more charity, and in this manner, as a son, he will cause joy to his deceased parents. But if he neglects the essential, Torah observance and good deeds, and adheres to the marginal [Kaddish], the soul of the deceased is unaffected.”

תחת להרבות בקדישים ירבה בלימוד ובצדקה, ובאופן זה יזכה בן את הוריו ויהי להם לקורת רוח. אבל אם יזניח את העיקר, דהיינו תורה ומעשים טובים, ויתפוס רק בטפל, אין קורת רוח לנפטרים כלל

הרב ישראל טאפלין, תאריך ישראל, סימן כ”ה, בשם הרב יוסף אליהו הענקין

Kaddish by Women:

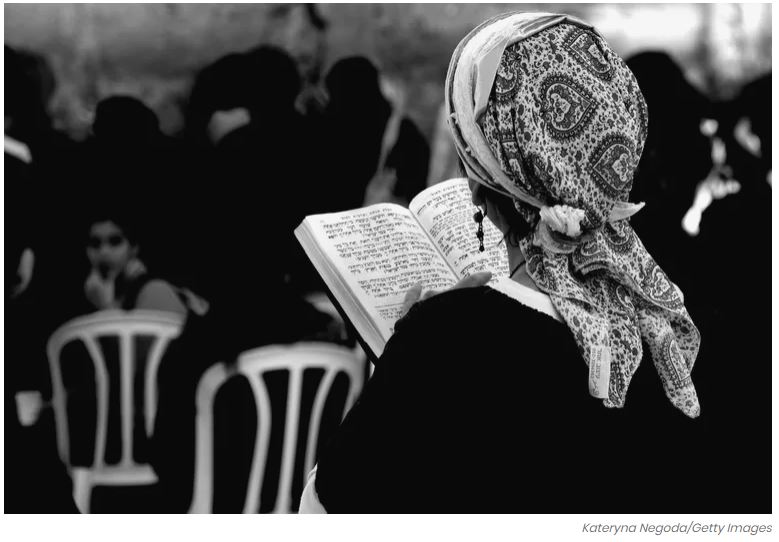

Following yesterday’s post, I have received an email from a woman who is within the year of mourning for her mother. She and her sister are saying Kaddish, but her sister had the unpleasant experience of being chased out by the congregants, despite the rabbi’s supportive attitude. She asked me to clarify the halakha regarding the reciting of Kaddish by women. Before I do so, however, I must quote here a Midrash that sprang to my mind upon reading her email:

מעשה באשה אחת שהביאה קומץ אחד של סולת להקריב מנחה, והיה הכהן מבזה עליה, ואומר: “ראו מה היא מקרבת! מה יש בזה להקריב? מה יש בזה להקטיר?” נראה לכהן בחלום: “אל תבזה עליה! מעלה אני עליה כאילו נפשה הקריבה!” (מדרש תהלים, מזמור כב)

A woman once brought a fistful of semolina as a thanksgiving offering. The priest scorned her, saying: “look at what she brought! What is there to sacrifice? What is there to burn?” He had a dream that night where he was told: “Do not scorn her! I [God] consider it as if she had sacrificed her soul!” (Midrash Tehillim, Ps. 22)

Just like the Midrashic woman who brought forth her soul, a mourning woman comes to shul to say Kaddish for her loved ones, and to pour her soul out. She is tormented and grieving no less, and perhaps more, than a man in the same situation. Who are we to judge her and to tell her that her sorrow does not justify a Kaddish in shul? Can we insist that saying Kaddish, expressing grief, and fulfilling one’s personal and societal duties, are rights reserved only for men?

Some would argue that traditionally, women did not say Kaddish in shul. This argument is only partially true, as will be shown later, but even if women never said Kaddish in the past, there would be no reason to block them from doing so now.

Let me explain: the practices of mourning change constantly in accordance with changes in lifestyle and societal norms. There is a long list of requirements mentioned in Tannaitic and Talmudic literature, and even in Shulhan Arukh, which are unheard of today, for example: sitting Shiva for grandparents, in-laws, stepchildren, nieces, and nephews; eulogies in the city plaza; a sub-period of two or three days at the beginning of Shiva; revealing one’s shoulders; hiring wailing women and bagpipe players for the funeral procession and many more.

All those changes point to one general rule: the mourning practices are not determined by legal considerations only, but by necessity, social norms, and most importantly, feelings and emotions. In other words, the Halakha never intended to regulate mourning but rather to facilitate the process. It comes to help the mourners express their grief, and to assist their circles of relatives and friends in offering the support system which is so desperately needed.

In the past, women perhaps did not see the need to say Kaddish, because they lived in small communities and were surrounded by close friends. It is very possible that the mourning women were comforted with the compassion and attentiveness their inner circle had to offer. The presumable lack of interest in saying Kaddish could also have been a result of the clear division between the roles of men and women in society. Today those two conditions have drastically changed. On one hand, women are integrated in all areas of modern life, and they feel that they deserve to express their grief or respect with Kaddish, just like men. On the other hand, like many men in modern society, they no longer have the luxury of personal and intimate relationship with a close circle of friends. Some people choose to turn to WhatsApp and Facebook for companionship, and some come to shul where at least God listens.

A good analogy for changes in social norms, which led women to the shul and let them interact with the regular Minyan, is Birkat haGomel. This blessing is recited by one who was saved from great danger. For many centuries, new mothers did not recite this blessing, despite the fact that their lives were in grave danger during delivery. Recently, however, there is a growing tendency to encourage women to say the blessing in the shul, in front of a minyan. Before the woman says the blessing, the cantor or Gabay asks the men to pay attention to her blessing and to say Amen. If a woman is allowed to say Birkat HaGomel, where the men are required to pay special attention to her, she should definitely be allowed to say Kaddish, even if she is the only one saying it.

In practice, Rabbi Avraham Yosef, the son of Hakham Ovadia Yosef, and Rabbi Eliyahu Abargel, both ruled that a woman can say Kaddish in the synagogue.

Rabbi Moshe Feinstein writes that it was a common practice for a mourning woman to enter the synagogue to say Kaddish, even without the separation of a Mehitzah (divider).

There is also the testimony of the author Yaakov Yehoshua (1905-1982), an author and historian of the old Sephardic community in Jerusalem, that it was customary to see women saying Kaddish in the Ashkenazi synagogues. He adds that Rabbi Shraga Faivel Frank of Yemin Moshe requested in his will that his daughters will say Kaddish for him.

Conclusion

It is true that there is no obligation to say the Kaddish, but if women chose, they are allowed to do so. They can recite the Kaddish in the synagogue or at the house of Shiva where there is a minyan. If the rabbi senses that saying Kaddish would help a mourning woman, he should encourage her to do so. It is also important for women and rabbis alike to educate the male congregants and to enlighten them to the Halakhic sources which allow women to say Kaddish. It would also help to ask them to try and understand the emotional state of the mourning women and the tremendous benefit they will have from saying Kaddish.

Sources:

יעקב יהושע, טורי ישרון, י:מא, עמ’ 22: נהוג היה בכמה מבתי הכנסיות האשכנזים שיתומות נהגו להגיד קדיש אחרי פטירת הורים, שלא השאירו אחריהם בנים זכרים… מספרים על הרב שרגא פייבל פרנק, רבה של שכונת ימין משה, כי בצואתו ביקש כי בנותיו תאמרנה אחריו קדיש, ואכן מסתבר כי לפי ההלכה נוהגות בנות להגיד קדיש

הרב משה פינשטיין, אגרות משה, אורח חיים, ה:יב: והנה בכל הדורות נהגו שלפעמים היתה נכנסת אשה ענייה לבית המדרש לקבל צדקה, או אבלה לומר קדיש

ילקוט יוסף, נטילת ידים וברכות, הערות סימן ריט: וכן כתב בכנסת הגדולה שיש לתמוה על מה שנהגו הנשים שלא לברך הגומל, שזהו מנהג בטעות. ואם מפני שצריכה לברך בפני עשרה ואין זה מכבודה, וכי טעם זה יספיק לפוטרה מחיובה, והרי אפשר לה לברך בעזרת הנשים וישמעו הקהל שבבית הכנסת