With the Corona virus spreading rapidly and new restrictions announced daily on public gathering, a question I have discussed a while ago is resurfacing:

When ten participants are in the same room only virtually and not physically, is it considered a Minyan?

To find the answer to this question I turned, naturally, to the internet, and Rabbi Google confirmed that two Jews have three opinions. While many congregations livestream services and classes, only few conduct online services. Some of them, like Universalist online congregation Sim Shalom, have been doing it since 2013, but the majority of congregations and rabbis still opposes the idea of a virtual Minyan. Here is a brief summary:

US Reform [theory]:

In responsa 5772.1 of the CCAR, the Reform Rabbinic leadership organization, the committee rules that “Whether through dial-in, live-streaming, or video connection, it is a good thing to encourage those who cannot attend the synagogue to be “technologically present.” Such persons, however, are not part of the minyan, because the minyan is the community of those are truly present with us, that is, in the real (as opposed to virtual) sense of that term.”

US Reform [practice]:

Rabbi Moshe Thomas Heyn of Temple Israel in Miami offers the congregants a virtual minyan. The Mourner’s Kaddish can be recited without physically being at Temple Israel. Chaya Lerner, who facilitates the Minyan with the rabbi, considers also the shul’s benefits: “The costs are minimal, as you eliminate the need of having extra security and staffing at the temple”. The minyan is often done from the rabbi’s office or any other location that can facilitate the Zoom technology, and it was attended by seven to ten participants weekly in its first four months.

UK Reform:

R. Jonathan Romain, rabbi of the Maidenhead [that’s its real name] Synagogue, says that “it may be nice that an uncle from Australia shows support by Skyping in, but it would be all too easy for those much closer to do so too, saving time their end but denuding you of their physical presence. The essence of a shivah is not fulfilling a numbers game, but of giving real actual support. So let us keep the obligation to show up in person and not encourage a convenient electronic absenteeism. Australian uncles maybe, but no one in driving distance.”

Conservative:

Rabbi Avram Israel Reisner, a faculty member of the JTS, ruled that a minyan may not be constituted over the Internet, through an audio or video conference or any other medium of long-distance communication. Only physical proximity, defined as being in the same room with the shaliah tzibbur (prayer leader), allows a quorum to be constituted.

Rabbi Jason Miller, who studied under Rabbi Reisner, calls for a reassessment of the ruling. He writes: “…Rabbi Reisner wanted to put his seal of approval on virtual minyans to allow the homebound and the business travelers to be part of a prayer quorum to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish, [but] the technology of the day could not meet the Jewish legal standards. But this was over a decade ago… Advances in virtual communication, bandwidth, video capabilities, and social media may make the virtual minyan possible…”

Orthodox:

R. Naftali Brawer, founder and CEO of Spiritual Capital, writes that a minyan must be formed by ten people in the same physical room. Once it is formed, one can join online to respond Amen in the appropriate places, but cannot recite Kaddish.

Chabad:

Rabbi Baruch S. Davidson writes: “…in a situation where some of the ten are outside but their faces are seen by the others, the Code of Jewish Law states that they may indeed be considered a minyan. One might argue that when using a group chat with webcam, all members of the quorum can indeed see each other’s faces.” That phrase seems to give hope to the virtual minyan, but he continues immediately to say that the allowance for including people who are outside only applies to those in “close proximity.” R. Davidson concludes that “while in some senses the internet has raised the degree of materialism in our society, in the sense of a minyan, it seems that the internet is too spiritual!” True to the Lubavitch spirit, he does not forget to include a call to action: “Search for the prayer times at the synagogue closest to you, and make a point to physically attend as often as possible (and leave your cellphone on silent or at home).”

Mysterious Consensus

The most amazing conclusion which I can draw from researching the different opinions on the matter, is that we have a rare example of consensus between the constantly warring factions of modern-day Judaism. While there are of course nuances in the way the ruling is phrased and practiced, there is an agreement that the Minyan should be conducted with ten people physically present.

What is the reason for that mysterious consensus? Is it Techphobia? Is it purely Halakhic? Or maybe there are other forces at play here?

Practical Arguments Against a Virtual Minyan

Some of the arguments against a virtual Minyan are Halakhic literature, while others are practical. Let us stat with the practical arguments:

- A

virtual minyan cannot provide a sense of community. - Virtual

reality will take over the real world and will isolate people.

The main practical argument is that a physical minyan provides a sense of community and camaraderie which a virtual Minyan could never replicate. This is the argument which the rabbis express and which many shulgoers, myself included, agree with. There is another argument, though, which is kept hidden, maybe for fear of being viewed as opportunistic and self-centered, and that is the concern about the centrality of the synagogue in people’s life.

I would like to believe that synagogues are not territorial. I would like to believe that your rabbi is happy that you attend a synagogue, whether it’s his or not. My experience with neighboring rabbis who would call my congregants and try to convince them to cross over is probably unique and isolated. However, I cannot help but feel that the consensus among all denominations that a virtual Minyan is not a good idea stems from the fear that the virtual world will take over reality, synagogue attendance will drop, and the financial stability of congregations will be undermined.

But let us return to the fear of losing the sense of community. That fear is not unique to Jews or to religious institutions. It is shared by parents, educators, vendors, entertainers – basically, anyone who is not providing virtual services of one kind or another. While I wholeheartedly agree that there is a great danger of becoming isolated and detached when one becomes submerged in the virtual world, I think that we should take a metaphorical Xanax and calm down, because people still want to be together. If virtual reality and web connectivity were the ultimate nirvana, it would be common to see empty sport stadiums, concert halls, movie theaters, restaurants, and even sidewalks. All those are full because most people want to be together. We are willing to have some solo experiences, some of the time, but not turn all our experiences, all of the time, into ones performed in solitude.

You might want to cuddle up at home and binge watch Netflix, but once in a while you might want to watch an exciting movie in the theater. When it seems that all the possible music has already been written, reality shows keep searching for the next great voice and fans fill up gigantic stadiums to hear live performances and to feel in-sync with tens of thousands of other fans. If our synagogues are feeling a drop in attendance, it is not because virtual prayers are replacing them but rather because most of the time there is no sense of excitement or exhilaration except for the occasional fight or gossip. I will return to the topic of improving our synagogue experience, but I do not think that the fear of losing congregants justifies an opposition to the virtual minyan.

The other fear is that many roles fulfilled by rabbis and religious entities will be taken over by bots. This is true and maybe even desirable when dealing with technical functions such as Kashrut supervision. Imagine one person in a command center overseeing all the Kosher meat production in the United States. This will save the Kashrut organizations millions of dollars and will allow them to significantly reduce the cost of kosher food (I am sure that right now they are busy planning exactly this!). Just as with the Industrial Revolution, it will cause loss of jobs but will allow people to divert their talent and time to more productive and intellectual pursuits. The technological revolution would not have been possible without the industrial one relieving workers of menial work and improving life quality.

This fear, however, should not be applied to the real role of the rabbi, which is to provide moral and emotional support, inspire and teach. People still want to learn face to face and in the company of others, and counseling, consoling, and officiating in life cycle events would always (or at least for the foreseeable future), be in the hands of humans.

Halakhic Arguments Against a Virtual Minyan

Let us turn now to the Halakhic arguments:

- Ten

people must be present to recite sacred liturgy – דבר

שבקדושה - Those

ten must be physically present in the same space.

Before we answer, let us consider the following:

Since our prayers are directed at God, when we say that the ten people forming a Minyan must be in one place, what is the definition of the place in relationship with God?

The Halakhic arguments against a virtual Minyan are that Ten people must be present to recite sacred liturgy – דבר שבקדושה, and that those ten must be physically present in the same space.

This halakha is tersely stated in Shulhan Arukh Orah Haim, 55:13:

צריך שיהיו כל העשרה במקום אחד

All ten must be in one place.

It is understandable why the sages of the Mishnah, who instituted the obligation of public daily prayer and created most of the basic laws surrounding it, wanted the participants to be in one place. Ten people are required specifically for דבר שבקדושה – sacred liturgy and reading the Torah. Those are the instances in which God’s name is exalted and His word to us is read publicly. Just as a governing body requires a quorum for a decision or even a discussion, the importance of those actions mandates that ten people will congregate to perform them. It is not that an individual prayer does not count, but to be considered תפילה בציבור – a communal prayer, where Kaddish and Kedusha are recited, a community is needed.

So, ten people who pray simultaneously but in separate places are not a community, but in relationship to whom are they considered separated?

They are separated from each other, but God knows of all of them. Had it been possible for them to know of each other’s actions, they would be able to congregate even though they are in remote places.

This is alluded to in Shulhan Arukh, Orah Haim 90:9:

ישתדל אדם להתפלל בבית הכנסת עם הציבור, ואם הוא אנוס שאינו יכול לבוא לבית הכנסת, יכוין להתפלל בשעה שהציבור מתפללים, והוא הדין בני אדם הדרים בישובים ואין להם מנין, מכל מקום יתפללו שחרית וערבית בזמן שהציבור מתפללים

One should strive to pray in the synagogue with the community. If he is unable to come to the synagogue, he should coordinate his prayer with that of the community. Similarly, those who live in [remote] villages and do not have a minyan, should pray Shaharit and Arvit at the same time the community prays.

The Mishnah Berurah explains (ibid. 29 and 32):

אנוס – היינו שתש כחו אף שאינו חולה. ואם הוא אונס ממון שמחמת השתדלותו להתפלל עם הצבור יבוא לידי הפסד יכול להתפלל בביתו ביחיד… בזמן שהצבור – פירוש בשעת שקהלות ישראל מתפללים

Unable – because of physical weakness, even if he is not sick. If it is a financial consideration, and he stands to lose money because of his insistence on praying with the community, he can pray at home alone… at the same time – meaning at the time the communities of Israel pray.

R. Tzvi Katz (Poland, 16-17th C) adds in Ateret Tzvi:

דכתיב [תהלים סט, יד] ואני תפלתי לך ה’ עת רצון, אימתי עת רצון, בשעה שהצבור מתפללין

It is written (Ps. 69:14) “I offer my prayer to You, God, in a favorable hour”, and a favorable hour is when the community prays.

We learn from these words that if one cannot come to the synagogue, he could coordinate his prayer with the community. That means that if one knows that others are praying and he prays along with them, God combines the prayer of the individual with that of the community. We also learn that one does not have to be bed ridden to be exempt from praying with the community. The daily routine might demand that one will be at work at a certain time or one could be too tired or weak to go. This is a reality which cannot be denied. With rare exceptions, every shul counts with more people on Shabbat and holidays than it does on weekdays.

And there is also the issue of remote places. Some people with whom I have discussed the question of virtual minyan argued that observant Jews to whom communal prayer is important should not live in remote places. This argument is detached from reality. There are many people who cannot afford to live near a major Jewish community, while others are forced, because of their work, to live in “remote places.” There are also thousands who are bed ridden at home or in a hospital, and who could benefit from a virtual minyan [this article was written seven months before the outbreak of the Corona Virus!]. And what about those who are traveling and must say Kaddish? And those unable to attend the synagogue because of inclement weather, natural phenomena, or rocket attacks?

The Shulhan Arukh (55:14) gives an example of people counting as a Minyan even though they are not all in the same place:

מי שעומד אחורי בית הכנסת וביניהם חלון, אפילו גבוה כמה קומות, אפילו אינו רחב ארבע, ומראה להם פניו משם מצטרף עמהם לעשרה

If one stands behind [e.g. outside] the synagogue, and there is a window [in the wall] between them, even if the window is several floors above the ground, and even if it is very narrow, if they can see his face from there, they can count him with the minyan.

Now, though the Shulhan Arukh spoke of Windows, he would probably agree that Mac or any other OS will do. This halakha makes it clear that it is important for the participants of the minyan to see each other, which is easily achievable with platforms such as Zoom or Go to Meetings. This is supported by a halakha quoted in Hishukay Hemmed by R. Yitzhak Zilberstein (Israel, 1934-) on Berakhot 21:1.

והנה עשרה יהודים המפוזרים על פני השדה, כל זמן שרואים אחד את השני ושומעים את קולו של הש”ץ או של האומר קדיש מצטרפים הם למנין

R. Zilberstein writes about people who visit the cemetery, saying that they could recite Kaddish by a grave, as long as they can see each other and hear the one saying Kaddish, even if they are far removed from each other. If we assume that one the Kaddish can be heard 30 feet away, then some of the participants of this Kaddish might be 60 feet apart, as one is to the right and the other to the left of the grave. Those two can see but not hear each other, yet they can join in prayer because they can see each other and hear the one saying Kaddish.

It is clear, therefore, that when ten people are present simultaneously in a virtual room, they meet all the requirements of the minyan because they can see and hear each other, and they can certainly acknowledge that they are all engaged in communal prayer. God, watching from above, would smile, because He always knew how people were connected, and He is now glad that they know it as well.

I would like to conclude with this beautiful teaching from the Talmud (San. 39:1), which seems to have been written with the virtual minyan in mind:

אמר ליה קיסר לרבן גמליאל: אמריתו, כל בי עשרה שכינתא שריא, כמה שכינתא איכא? …אמר ליה: אמאי על שמשא בביתיה דקיסר? אמר ליה: שמשא אכולי עלמא ניחא. [אמר ליה] ומה שמשא, דחד מן אלף אלפי רבוא שמשי דקמי קודשא בריך הוא, ניחא לכולי עלמא, שכינתא דקודשא בריך הוא על אחת כמה וכמה

The emperor asked Rabban Gamliel: you say that wherever there are ten people the Divine Providence, Shekhina, is found, how many Shekhinas are there?

[Rabban Gamliel] asked: How come there is sunlight in your house?

The emperor answered: the sun shines for the whole world.

Rabban Gamliel said: if the sun, which is one of trillions of God’s servants, can shine for the whole world, how much more so God’s Divine Providence [can come and visit any ten people who are joining in prayer]!

Let us pray for good health and speedy recovery for all!

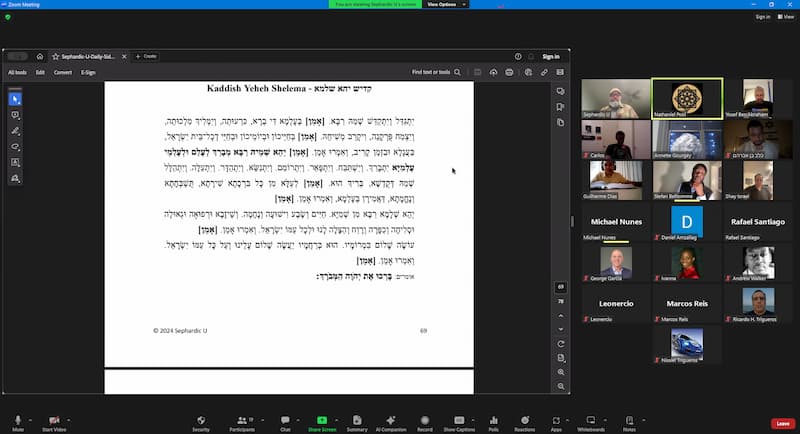

Join our live minyan and connect with others from the convenience of your own location for a meaningful prayer experience.

Don’t forget to check our calendar.