Prayers and Sacrifices

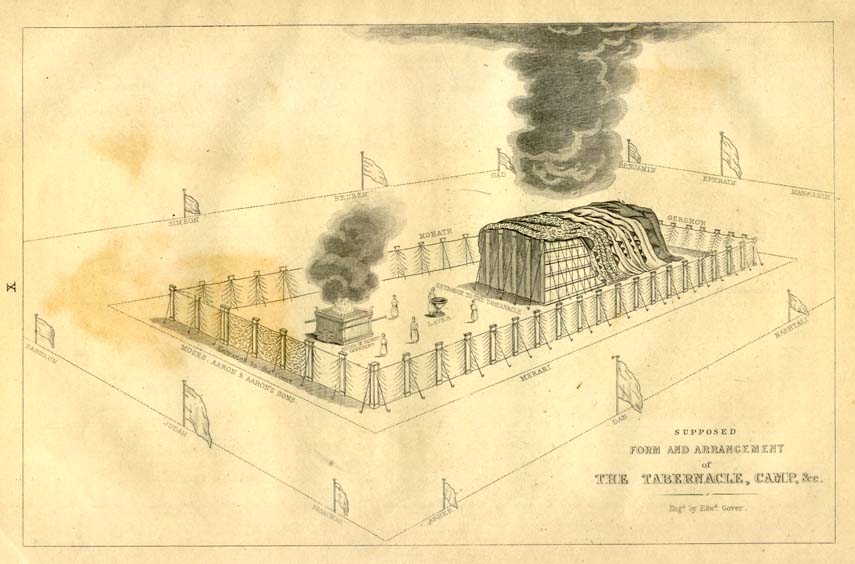

The sages of the Midrash argue that there is a deep relationship between sacrifices and prayers:

Rabbi Yehoshua Ben Levi said: Prayers were established as a substitute for the daily sacrifices (Berakhot 26:2).

Rabbi Avho said: What replaces the oxen we used to sacrifice to You? Our lips, through the prayers we pray to You (Pesikta DeRav Kahana, 24).

This argument is a result of the deep void caused by the destruction of the Second Temple. Tradition attributes the texts of certain prayers to Ezra the Scribe and the Great Assembly, starting in the 6th century BCE, but it is quite obvious that the prayers were formed and established after the destruction. While it is true that people offered prayers already at the time of the Temple, there were no set times or a fixed formula for those prayers.

What was the role of prayers in daily life in antiquity? The main difference between sacrifices and prayers was that sacrifices were offered by a small group of cohanim representing the whole nation, while prayers were recited individually.

Why Are There No More Sacrifices?

Both temples were destroyed because their purpose was distorted. People saw the sacrifices as a payment for their sins, a payment which allowed them to start a new round. The idea that a sacrifice is a payment or negotiation with God can be found in the Torah in Balaam’s attempt to convince God to allow him to curse the Israelites by offering dozens of sacrifices. In later biblical books there is harsh criticism of those who saw sacrifices and prayers as a tool for forgiveness but never changed their behavior:

In the first chapter of Isaiah we read (1:10-17):

Do not bring vain offerings… I cannot tolerate your new month, Shabbat, and holidays… your assemblies have no positive purpose… I am burdened by your celebration… when you raise your hands in prayer I will look away, and though you utter many prayers I will not hear, your hands are stained with blood and corruption… Wash and purify yourselves… cease your evil deeds… learn well, seek justice, rectify injustice, and protect orphans and widows…

This passage is particularly significant because the prophet mentions not only sacrifices, but prayers as well. It is very strongly worded, suggesting that God rejects the offerings of the people, whether physical or spiritual, and does not want them to visit His temple. The prophet insists that God’s service is not about serving or worshiping Him, but rather about working in His name to bring justice and comfort to the less fortunate.

The Wicked Fist

This theme continues in Isaiah 58 and 59: The prophet describes those the people who wonder why their prayers are rejected:

They seek Me daily! They want to understand My ways! As if they were a just nation, one who follows God’s commandments. They demand justice, they ask to be close to God. They say, why have we fasted and You have not seen, why have we afflicted our soul and You did not pay heed?

It is because you dedicate your fast day to your personal affairs and to oppressing the poor! As you fast, you fight and quarrel, striking others with a wicked fist…

This is the fast day I want: release prisoners of injustice and remove the yoke of oppression… share your bread with the hungry, bring the poor into your home, and dress those in need, for all humans are your own flesh and blood…

And what about us? Can we claim that Isaiah’s criticism does not apply to us? Are we transformed by the experience of prayers?

Isaiah speaks of those who hit others with the fist of evil. During my first Rosh HaShana in the US, a dispute erupted over the tune for the opening Piyyut for Arvit. I was a young visiting Hazzan and before I had a chance to start services, one of the congregants started chanting his version. He apparently had a history of hijacking prayers, and another man yelled at him to keep quiet and stop disturbing. The first man fell silent, we chanted the Piyyut, the rabbi delivered an uplifting sermon, and we prayed the first Arvit of the new Hebrew year of 5749. When Arvit was over, the chanting man got up, turned around, and punched his critic in the face. How inspiring!

A Ticket to Heaven

Let us to go back to Tanakh now and read the words of Yirmeyhau, delivered shortly before the destruction of the First Temple (chapter 7):

Hear the word of God, oh people of Yehudah… the Temple… will not help you unless you correct your ways and your evil actions! You must serve justice in the disputes between one man and another…

Do you think that you can steal, murder, commit adultery, and make false oaths… and still come and stand in front of Me, in this house which bears My name, and say: “we are now cleared of sin, so we can go back to commit all those crimes”?

These words remind us of the practices of the Catholic church in Medieval times. For a considerable donation, the sinning faithful could buy a ticket to heaven. I would like to think that there is no room for such practices in Judaism, and that one cannot expect to buy his little patch of heaven by reciting routine prayers or by giving money to spiritual leaders.

Adultery and Idolatry

Another prophet who expresses similar sentiments is Malachi, who was active in the early years of the Second Temple (at around 510 BCE). He rebukes the priests who turned the Temple into a business and also addresses the people who see sacrifices as a cure-all.

You have covered God’s altar with tears and screams, [so how can I] pay heed to your offering or receive your sacrifices?

You ask: “what have we done?”

God will testify between you and the wife of your youth whom you have betrayed, the one who was for you a friend and an ally…

The husband’s betrayal of his wife is both a metaphor for idolatry and a reference to adultery. More than that, it is a symbol for relationships based on self-interest. Spouses often drift apart when their common goals, such as raising a family or buying a house, are achieved. Those who serve God by rote, without being inspired by the prayers, are there only as long as the relationship serves their narrow interests.

King David Speaks

These prophets have painted a gloomy biblical landscape, an arid desert devoid of spiritual water, speckled with the whitening skeletons of rejected sacrifices. Let us conclude our journey by returning to the days of the First Temple and to the Book of Psalms (chapter 50):

Listen, my nation, as I speak! Israel, as I testify! I am your God!

I will not rebuke you for lack of sacrifices, as I constantly see your offerings…

Even if I were hungry, I would not tell you, for the whole world is mine;

Do you think that I consume the flesh of oxen and the blood of rams?

In these verses the author ridicules those who think that God needs our sacrifices, following the primitive notion of an angry and hungry god who must be appeased.

…Elohim says: “how dare you speak of My laws, mention My covenant?

The true sacrifice is showing gratitude for God’s blessings, and the way to redemption is to embark on the pathway of God…

Save Our Prayers

Just like the sacrifices of the past, our current system of prayers has fallen into the dangerous pattern described by our prophets millennia ago. While it is true that there are many instances in which we feel uplifted and inspired by prayers, those are few and far between.

It is true that prayers give us a sense of community and togetherness, especially when we are experiencing hardships. There is also something comforting and reassuring in reading the same texts, day after day, in a ritualistic manner. But there are many problems with our prayers: incessant talking, a feeling of boredom, hard- to-understand texts, and a sense of endless repetition. Let us contemplate ways to make our prayers count for us, so they could be a worthwhile substitute for the sacrifices of the past.

Questions for Kids: Parashat VaYikra

What is the root of the word וַיִּקְרָא?

Why did God have to call מֹשֶׁה?

What is the root of the word קָרְבָּן?

What is the message of that word?

Today what do we have instead of the קָרְבָּנוֹת?

Who was in charge of the קָרְבָּנוֹת?

Who is in charge of the תְּפִלּוֹת?

The קָרְבָּנוֹת were offered for three main reasons. What are they?

Which three words in Hebrew can describe these three reasons?

How many תְּפִלּוֹת are there daily?

What are the names of these תְּפִלּוֹת?

Which of these names is also the name of a קָרְבָּן?

What is the meaning of this word?

At the end of the Parasha we read about a קָרְבָּן which a person must bring for very serious sins. What are these sins?

Answers to Questions for Kids

- קָרָא – to call.

- Because the Mishkan was filled with קְדֻשָּׁה and משה could not come in if he were not invited.

- קרב/קָרוֹב.

- That the קָרְבָּנוֹת bring us closer to ה’.

- תְּפִלּוֹת.

- The כֹּהֲנִים.

- Each of us, and we are guided by the rabbis and teachers.

- To thank ה’, ask for forgiveness, and ask for our needs.

- תּוֹדָה, סְלִיחָה, בְּבַקָּשָׁה.

- Three.

- שַׁחֲרִית, מִנְחָה, וְעַרְבִית.

- מנחה.

- A gift.

- Stealing from another person or cheating another person.

- That the Torah wants to teach us to be nice to one another and respect one another.

Parashat Behar – Weekday Torah Reading (Moroccan TeAmim)