For Parashat Noah

Genesis is the Book of Communication. Even before mankind is introduced, God creates the universe uttering words which become reality. Not only that, even the inanimate elements mentioned in the opening verses of the creation – the heavens, the earth, the abyss, God’s spirit, and the water – are described elsewhere in the Bible as communicating through word, voice, or song, as we can see in the following verses:

הַשָּׁמַ֗יִם מְֽסַפְּרִ֥ים כְּבֽוֹד־אֵ֑ל וּֽמַעֲשֵׂ֥ה יָ֝דָ֗יו מַגִּ֥יד הָרָקִֽיעַ׃

The heavens speak of God’s glory and the firmament talks of His handiworks (Ps. 19:2)

וַיהוָ֞ה מִצִּיּ֣וֹן יִשְׁאָ֗ג וּמִירוּשָׁלִַ֙ם֙ יִתֵּ֣ן קוֹל֔וֹ וְרָעֲשׁ֖וּ שָׁמַ֣יִם וָאָ֑רֶץ וַֽיהוָה֙ מַֽחֲסֶ֣ה לְעַמּ֔וֹ וּמָע֖וֹז לִבְנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

God roars from Zion, shouts from Jerusalem, Heaven and Earth raise their voice (Joel 4:16)

תְּהֽוֹם־אֶל־תְּה֣וֹם ק֭וֹרֵא לְק֣וֹל צִנּוֹרֶ֑יךָ

Through the waves, one abyss calls to another (Ps. 42:8)

ר֥וּחַ יְהוָ֖ה דִּבֶּר־בִּ֑י וּמִלָּת֖וֹ עַל־לְשׁוֹנִֽי׃

The spirit of God spoke in me. And His word is on my tongue (II Sam. 23:2)

The metaphors of natural phenomena talking to each other and the concept of Divine creation through utterance, receive a renewed and much deeper meaning in modern times with the realization that life, nature, and as a matter of fact the whole universe, are engaged in constant communication – sub-particles, DNA, genes, and viruses (and of course coding, or as they used to call it when I studied Cobol and Fortran in the late 70’s – programming.)

Our immediate association of language, however, is with mankind, and indeed, the rabbis brilliantly related the creation of man to the invention of language by translating Genesis 2:7 as saying: “and man became a talking spirit.”

Since Genesis, more than any other book in the bible, deals with interactions between individuals, it provides a wealth of examples for both failed and successful communication. Among the successful ones we can count Abraham’s negotiation with God as he attempts to save Sodom, his dealing with the Hittites, his servant’s negotiation with the family of Rivka, and Joseph’s way of getting Pharaoh to grant his wishes.

The failures, unfortunately, outnumber the successes. Cain fails to communicate with his brother and eventually kills him, while God’s intervention in the dispute didn’t help much. Sarah and Hagar are unable to see eye to eye and their relationship, with Abraham in the middle, end in harassment and exile. Yitzhak and Rivka never to talk to each other about their children, thus setting an example for them, and landing them in an entanglement of hatred and deceit which lasted centuries, if not millennia. Joseph fails to understand his brothers who, after throwing him to the pit, cannot bring themselves to talk to their father about what happened.

This is not meant to put the readers in a negative mood. After all, we can learn from failure as much as from success, if not more. The narrative of Genesis is imperative for our understanding of human nature, family dynamics, sibling rivalry, and the recognition that even the greatest human being is susceptible to errors and wrong judgment when dealing with others.

If we return now to failed communication it seems that the story of the Tower of Babel is the epitome of such failure:

וְַֽ ַֽיְּ הִ ִ֥ יַ֗כָּׁל־הָּׁ אָּׁ ׁ֖ רֶ ץַ֗שָּׁ פָּׁ ּ֣ הַ֗אֶ חָּׁ ֵ֑תַ֗ודְּ בָּׁ רִ ׁ֖ יםַ֗אֲחָּׁ דִ ְֽ ים…ַ֗וַיֹּאמְּ ר֞ וַ֗הָּׁ ּ֣ בָּׁ ה׀ַ֗נִ בְּ נֶה־לָּׁ ּ֣ נוַ֗עִ ירַ֗ומִ גְּ דָּׁ לַ֙֗וְּ רֹּאשּ֣ ֹוַ֗בַ שָּׁ מַ֔ יִַ֗םַ֗וְּ נְַֽ עֲשֶ ה־ לָּׁ ׁ֖נוַ֗ש ֵַ֑֗םַ֗פֶן־נָּׁפׁ֖ וץַ֗עַ ל־פְּ נ ִ֥יַ֗כָּׁל־הָּׁ אְָּֽׁ רֶ ץ, וַי ַּֽ֣רֶ דַ֗ה’ לִ רְּ אִֹּ֥ תַ֗אֶ ת־הָּׁ עִ ׁ֖ ירַ֗וְּ אֶ ת־הַ מִ גְּ דָּׁ ֵ֑ לַ֗אֲשֶ ִ֥ רַ֗בָּׁ נׁ֖ וַ֗בְּ נ ִ֥יַ֗הָּׁ אָּׁ דְָּֽׁ םַ֗וַיֹּּ֣ אמֶ רַ֗ ה’ ה ּ֣ ןַ֗עַ ַ֤םַ֗אֶ חָּׁ ד֙ ַ֗וְּ שָּׁ פָּׁ ַ֤הַ֗אַ חַ ת֙ ַ֗לְּ כֻלָּׁ֔ םַ֗וְּ זֶ ׁ֖הַ֗הַ חִ לָּׁ ּ֣ םַ֗לַעֲשֵ֑ ֹות, ְּו ַע ָּׁת ֙ה ְֽלֹּא־ִי ָּׁב ּ֣צר מ ֶ֔הם ֹֹּּ֛כל ֲא ִֶ֥שר ָּׁי ְּזׁ֖מו ְַֽל ֲע ְֽשֹות. הָָּׁ֚ בָּׁ הַ֗ ְֽנְּר ָּׁ֔דה ְּוָּׁנ ְּבִָּׁ֥לה ִָּׁ֥שם ְּשָּׁפְָּֽׁתם ֲא ֶש ֙ר ּ֣לֹּא ִי ְּש ְּמ ֔עו ִׁ֖איש ְּשִַ֥פת ר ְֽעהו ַוִַָּׁ֙י ֶפץ ה’ ֹּאָֹּּׁ֛תם ִמ ָּׁׁ֖שם ַעל־ ְּפ ּ֣ני ָּׁכל־ָּׁהֵָּׁ֑אֶרץ ְַֽוַי ְּח ְּדׁ֖לו לִ בְּ נִֹּ֥ תַ֗הָּׁ עִ ְֽ יר֗

Now everyone spoke the same language and the same words… they said: “let us build a city with a tower reaching the heavens, let us make a name for ourselves or we will be scattered all over the world.”

God went down to see the city and tower built by men. He said: “they are one nation with one language. This is only the beginning and now they will be able to achieve all their goals. Let us scramble their language, so they will not understand each other.”

God scattered them all over the world and they abandoned the construction of the city.”

This is how Rashi (Gen. 11:7) describes the mayhem which ensued God’s intervention and His “mixing-up” man’s language:

זהַ֗ שואלַ֗ לבנהַ֗ וזהַ֗ מביאַ֗ טיט,ַ֗ וזהַ֗ עומדַ֗ עליוַ֗ ופוצעַ֗ אתַ֗ מוחו

When a worker would ask for a brick, his co-worker would bring mortar, and that would lead to fatal quarrels.

This Midrashic interpretation could serve as a great opener for discussing language barriers, cultural differences, and the importance of mutual understanding, whether you talk to young kids or to octogenarians (of course, without the violence element), but this famous story of the Tower of Babel raises many questions:

- What was the sin of the builders of the tower, why were they punished, and why was this strange punishment chosen?

- Was God afraid of the prowess and intelligence of humans?

- Wouldn’t it be better to disrupt their plan rather than create a linguistic mayhem, which seems to be the source of many cultural ethnic wars?

These questions led the authors of the Midrash to describe the Tower as an act of rebellion against God, and to suggest that some of the builders used the tower as a raised platform to shoot arrows towards heaven, in an attempt to defeat God. That version goes on to say that God played a prank on the shooters and the arrows fell back to earth covered in blood, thus making hem believe that they killed, or at least wounded, God.

In Defiance of Totalitarian Regimes

Unfortunately, this approach misses the main point of the story. There was no transgression, and therefore no punishment. God was not concerned about what humans did but about what they set out to do. The two words אחדיםַ֗ ודברים which I previously translated as “same words” should be actually read as “one ideology.” The Torah warns us of the danger in forming single-minded, authoritarian dictatorships. Governments such as now defunct Soviet Union, or current North Korea, invest heavily in military prowess and monuments, while civilians die of hunger or executed for ideological crimes.

George Orwell envisioned this terrifying possibility in his iconic 1984, in which the government creates a uniform language – Newspeak, to eliminate all chances of free will and creative thinking:

The whole climate of thought will be different. In fact, there will be no thought, as we understand it now. Orthodoxy means not thinking – not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness…

It’s a beautiful thing, the Destruction of words. Of course, the great wastage is in the verbs and adjectives, but there are hundreds of nouns that can be got rid of as well. It isn’t only the synonyms; there are also the antonyms. After all, what justification is there for a word, which is simply the opposite of some other word?

In the end, we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined…

This mentality is not restricted to tyrants and dictators, it could also be found in religious movements, educational establishments, the military, and the corporate world. The first group targeted by those who seek to establish control in any field, is that of the free thinkers, artists, poets, and writers. Many religious movements allow only certified music, literature, and entertainment, if at all, and most of them demand that their followers adhere to a strict dress code and ideological dogmas.

History has proven again and again that the spirit of man, the will for freedom, cannot be subdued. We all remember great quotes, speeches, statements, and poems which moved and inspired us. For the survival of mankind, it is essential that a variety of languages, and of dialects within one language will exist, not only because they enrich the fabric of our life, but because they allow mankind to perceive the world in myriad ways and from endless angles. The variety of languages, and the innate ability of language to constantly change, help us stay in perpetuum mobile, constant movement, rather than live a life which is no more than a slide show of freeze frames.

Writes John McWorther in his thrilling natural history of language, aptly titled The Power of Babel (p. 16):

Language, too, is change. All human speech varieties are always in a constant process of transformation into what eventually will be so different as to be a new language entirely. This change is certainly influenced by historical, social, and cultural conditions but it is not caused by them alone; the change would continue apace even without these things. Human speech transforms itself through time just as vigorously…

To summarize, when the Torah says that God scrambled human languages, it was not a punishment but a gift. By doing so God gave humanity the gift of creativity and diversity, and the promise that whenever a tyrant tries to squash an idea or a thought by enforcing “one language and one ideology”, there will be those who will be able to oppose his schemes using the gift of language and ingenuity.

Shabbat Shalom

Rabbi Haim Ovadia

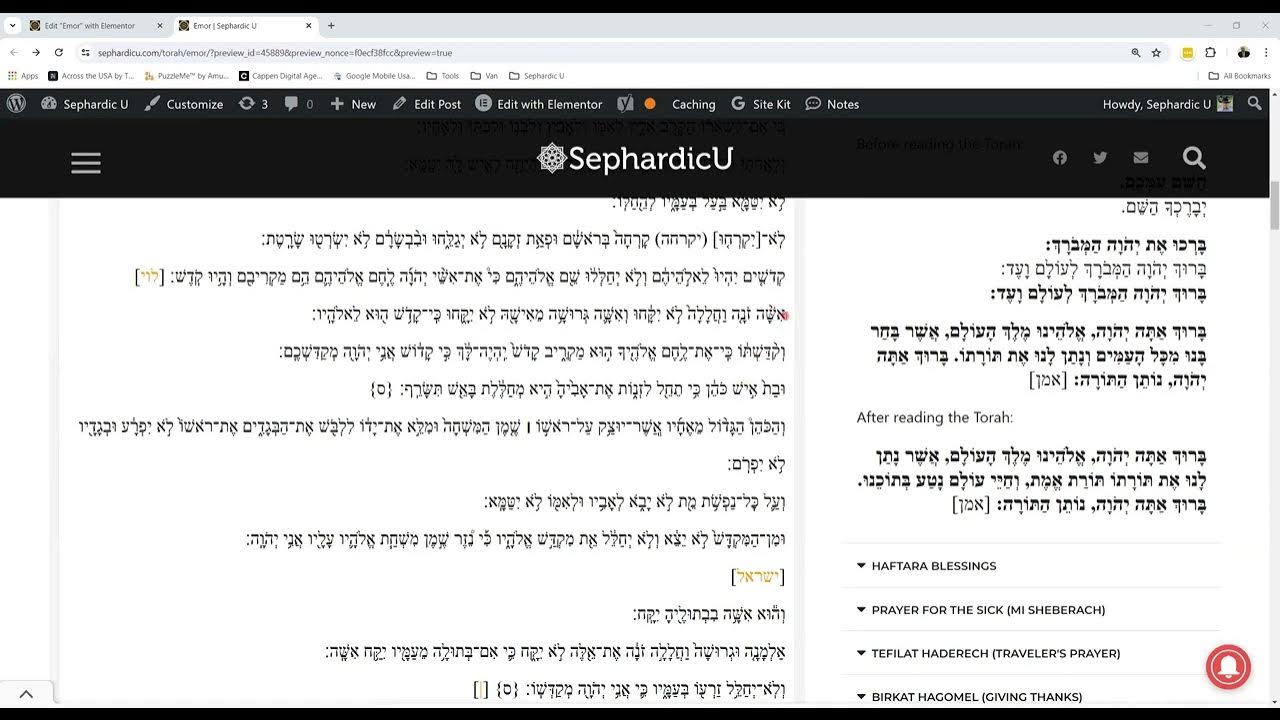

Parashat Behar – Weekday Torah Reading (Moroccan TeAmim)