In a famous passage in Exodus, God reveals some of His ways to Moses, who is hidden at the crevice of the rock. This very powerful passage is recited numerous times on Kippur with great enthusiasm. To continue the prayer, skip to the next Hebrew section. If you wish to better understand the message of this paragraph and how it applies to our current life, here is a reflection on it:

Spiritual Intimacy

Immediately following the preposterous transgression of the Israelites, the making and worshipping of a molten idol so shortly after the momentous occasion of the Giving of the Law on Mount Sinai, and after pleading with God to show mercy to the rebellious nation, Moshe approaches God with a request which seems to be out of place. “Show mw”, He says, “Your ways, so I may know You”, and goes on to explain that he deserves that knowledge because God told him that he has gained God’s favor and grace, so getting to know God will be a proof of the divine favor and grace. The result of that request was a mystical, breathtaking event for Moshe, in which he was hidden in the crevice of the rock while God passed His glory before him, proclaiming:

“… I am a God compassionate and gracious; slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness to thousands, forgiving iniquity, transgression and sin.

Yet I do not remit all punishment, but visit the iniquity of parents upon children, and children’s children, upon the third and fourth generation”.

The dichotomy of the proclamation, showing God as both a merciful and vengeful God, has prompted the rabbis to explain that Moshe’s request was to understand the duality of God’s ways in dealing with His world and His creatures. Moshe wanted to understand theodicy, Divine justice, why do the righteous suffer while the evil doers flourish.

Although this not only is a valid question, but probably the most pressing one for a believer, it does not belong here, in the context of the Golden Calf. God was about to punish the sinners and reward Moshe, according to the Divine plan of reward and punishment, so there was nothing out of the ordinary to justify such a request.

The clue to the nature of the request may be in the way it was formulated: “You have said that I have gained Your favor” says Moshe, “so how shall I know that this is true unless you let me know You and Your ways better?” These are words one might hear from a spouse or a loved one, demanding to have a proof for the love and the stability of the relationship and suggesting that by getting to know each other better they will be able to foster the relationship. Indeed, the biblical dialog most resembling this one is between a wife and her husband, although it is one of treachery and deceit:

“Then Delilah said to him: How can you say you love me, when you don’t confide in me? … you haven’t told me what makes you so strong.” (Judges 16:15)

Moshe demands from God an intimate relationship, not only for himself, but for the people, because Moshe and Israel are one, united by his responsibility and love for them, despite their iniquities. Moshe argues that worship and service alone do not suffice. The promise he received before the exodus that the people will serve God on Mount Sinai was understood by them as a concrete, carnal affair and not an abstract concept.

Moshe wanted to know how one can constantly infuse his life with religious and spiritual excitement, and it is not a coincidence he chose the verb ידע – to know, which in the bible connotes deep intimacy. Just as a marriage can go stale with the spouses going through the motions of their daily life, two people who happen to share assets, memories and offspring, so can spiritual life. The observant person, who might have been excited when he was first introduced to the rituals and accepted as a full-fledged member of the adult congregation, comes to a stage where he knows exactly what to do, when to do it, how to fulfil his responsibilities towards God and what to expect in return. So many people find themselves in a midlife religious crisis, going through the motions, following the routine, the book, but with no spark, no excitement and no anticipation.

Moshe’s request, then, is an argument in his people’s favor: they have sinned because they only know the rigidity of the law, the service of God, but if they would have known God, with love and passion as one spouse loves the other, it would not have happened.

This interpretation is in line with numerous biblical references which analogize the relationship between man and God to that of husband and wife. Most famous is the Song of Songs, but these comparisons can be also found in Isaiah (49:14-21; 50:1; 54:1-8) Jeremiah (2:1-2; 3:1-5) and many more. It is that analogy which inspired the mystics of Safed to create a special matrimonial ceremony on Friday nights, standing atop the magnificent Galilean mountains and welcoming the Shabbat, the covenant between us and God, in the same way the groom welcomes his bride:

לְכָה דּוֹדִי לִקְרַאת כַּלָה, פְּנֵי שַׁבָּת נְקַבְּלָה

God’s fulfilment of Moshe’s request, as a matter of fact, is not only a key to a better spiritual life, but to a better marital life as well. God explains that part of the relationship is responsibility and caretaking. Visiting the iniquities upon third and fourth generations means that although one can be forgiving, there must be a limit when destructive behavior is evident. When a parent fails to take care of his children and they are therefore in danger, the other parent cannot stand idly by. When spouses don’t treat each other with love and respect their direct descendants will bear the terrible consequences, and the same concept is applied to man’s relationship with God in regards to keeping the laws between him and God.

Mercy, kindness and graciousness, on the other hand, can infuse the relationship with a sense of commitment, gratitude and dependence. In the spiritual realm, this is translated to the laws between us and other people which, unlike the rote of ritual, can always give us new insights, excitement and raison d’etre. The elation from giving another person is more than charity and it is not only monetary. It is giving and sharing time, attention, advice and compassion, and it is extended, as the verse says, to thousands. Every person we meet and interact with can teach us something new about the world and about ourselves, and when the interaction is one of loving kindness, of seeing and connecting with the humanity in the other, it is an uplifting and inspirational one.

But the greatest lesson to be learned from the exchange between Moshe and God, from Moshe hiding in the crevice of the rock and from God passing His glory before him, is not from the words but rather from the setting:

“God told Moshe: you will not be able to see My face, for man cannot see Me while alive, you will only be able to see My back…”

In the quest for God as well as in the quest for love, there should always be an unknown. Husband and wife should be able to constantly seek for and find new facets of their beloved they are not familiar with, and it will fill them with a sense of elusiveness, mystery and longing, which in turn will breed love and passion.

And so should it be with our quest for God, which is in essence a search for self and meaning. Man should strive to constantly learn and grow, intellectually and emotionally, from the world of Torah, as well as science and nature, but also from discovering himself.

If we see the scene described above as a parable, then man is both the prophet and the image of God, he sometimes hides in the crevice of the rock, feeling lost and cowering in the dark, and sometimes pursuing a dream or a vision, tantalizingly close but always a step ahead, seen only from the back.

Then, towards the end of a wholesome, compassionate life, a life of emulating God’s attributes, showing responsibility and honesty, yet treating others with love and compassion, man finally reaches the elusive image, and when it turns to look at him, he knows: I have found God, I have found myself…

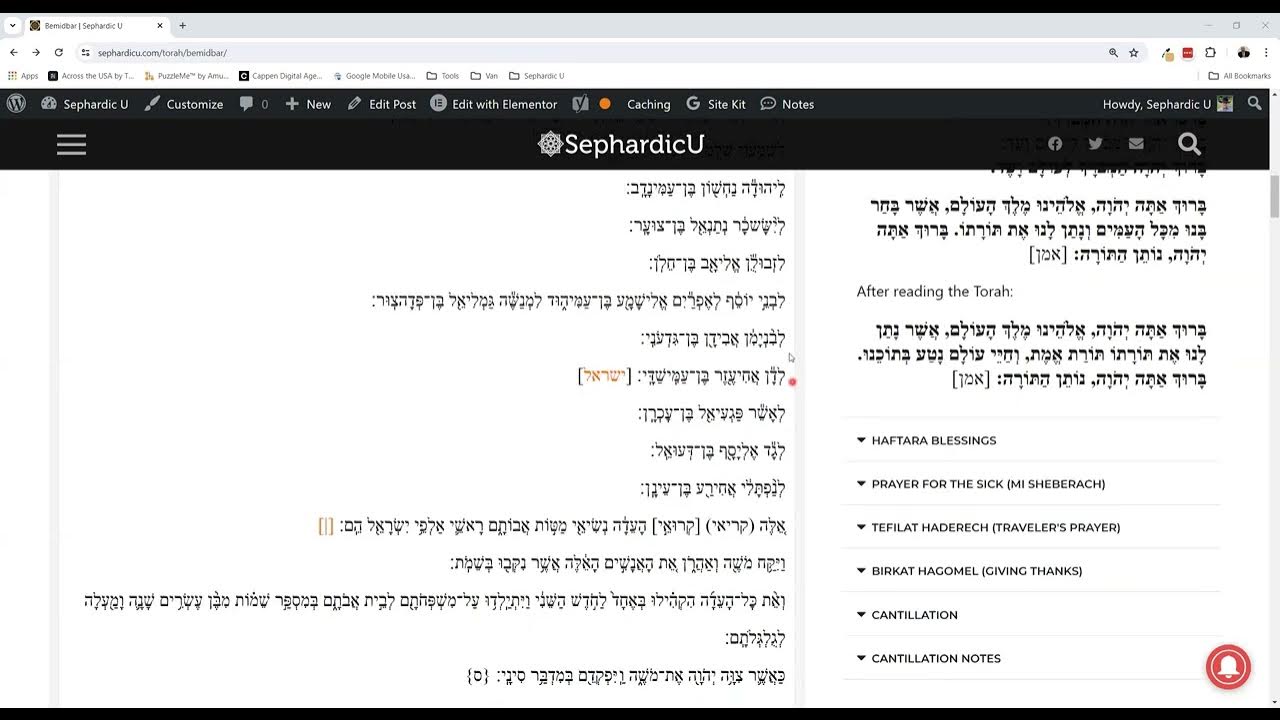

Parashat Bemidbar – English reading