The Portable Holy Temple

The movable tabernacle that the Israelites carried with them in in the wilderness was the mishkan, which is first referenced in the Torah in Exodus 25. The word “mishkan” means “to dwell” in Hebrew, and the tabernacle was seen as God’s earthly abode.

He commanded Moses to instruct the People to construct a mikdash (sanctuary) where He may reside, giving precise design instructions for the tabernacle in Exodus 25:8–9.

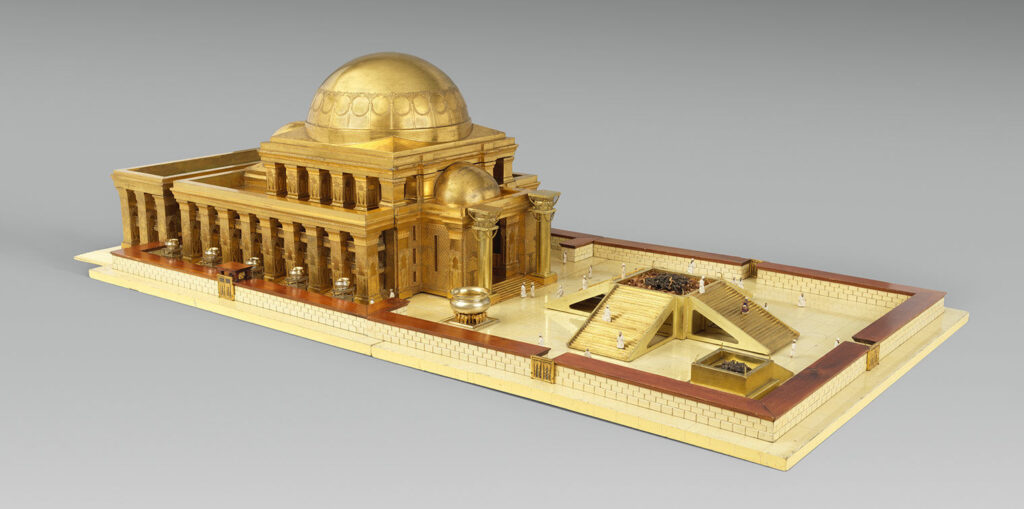

How the Tabernacle Looked

The design and building of the tabernacle are described in great detail in the Book of Exodus. A rectangular fence with a gate encircled the tabernacle, enclosing an exterior courtyard. In the courtyard was an altar for burnt offerings (sacrifices). A screen separated the “Holy Spot” from the surrounding area further into the courtyard. The “most holy place,” known as the Holy of Holies, was separated from the surface by a curtain.

The ark of the covenant, which held the tablets of the law, was to be housed in this innermost and most holy area of the tabernacle. The ark was to be made of acacia wood with pure gold inlay. The Torah specifies the dimensions of the ark: “two and a half cubits long, a cubit and a half wide, and a cubit and a half high” (Exodus 25:10). Acacia poles with gold inlay were used to transport the ark through the desert. The ark needed a cover with two gold cherubim (angels), one on each side, facing each other with outstretched wings.

Other instructions include making a table, “bowls, ladles, jars, and jugs,” and an intricately designed six-branched menorah, or candelabra (Exodus 25:29-38). Exodus 26 describes the tabernacle’s construction, which was a tent-like structure covered with ten strips of linen cloth. The cloth was to be made of blue, purple, and crimson yarn, with the cherubim motif repeated from the ark cover.

The text goes on to specify how many loops and gold clasps should be used to tie each cloth to the next. It goes on to say that 11 goat hair cloths connected by loops and copper clasps should cover the tabernacle. Furthermore, ram and dolphin skins were to be used as additional coverings for the tabernacle.

The Importance of the Tabernacle

The tabernacle was thought to be the location of God’s presence among the Israelites, where the divine and earthly realms met. The design of the tabernacle physically represented a gradual increase in holiness, from the outer courtyard (meant to create a barrier between the profane and sacred realms) to the Holy of Holies (only entered once a year on Yom Kippur by the High Priest).

The portability of the tabernacle foreshadows the Jewish people’s future movements in exile, where they built synagogues and houses of study wherever they went. The tabernacle also represents the paradox of divine presence in the world: on the one hand, God is believed to be everywhere, but on the other hand, the tabernacle (and later the Temple in Jerusalem and synagogues worldwide) represents a physical location where humans can experience a connection to God.

Tabernacle versus Temple

The Holy Temple in Jerusalem, built by King Solomon in 957 BCE, became the permanent sanctuary for the Israelites to worship God (until it was destroyed and later rebuilt and destroyed again). They used the tabernacle as a portable sanctuary while wandering in the desert.

The Tabernacle’s Archaeological Evidence

In 2013, it was reported that possible evidence of the tabernacle had been discovered in the ancient West Bank city of Shiloh. Archaeologists discovered holes hewn into the rock that may have been used to support the tabernacle’s wooden beams. Previous research at the site discovered the remains of possibly sacrificed animals as well as evidence of bathing pools where the High Priest may have cleansed himself before entering the tabernacle.

Watch our 3-Part Webinar Series on “Building the Tabernacle (Mishkan)”

Some Facts About the Mishkan

| Interesting Facts About the Mishkan |

|---|

| Betzalel and Aholiav were in charge of construction. |

| The people donated the materials for the Mishkan, and they gave so generously and freely that Moses had to tell them to stop. |

| The actual construction was carried out by a group of motivated and skilled men and women. They were led by two men named Betzalel and Aholiav at God’s command. Betzalel came from a prominent family and was related to Moses. Aholiav, on the other hand, came from the most humble of backgrounds, the Dan tribe. But it made no difference because everyone contributed to the best of their abilities. |

| There was a central structure. |

| The Torah goes into great detail about the exact dimensions of the Mishkan and the materials used to construct it. |

| The Mishkan itself was a box-shaped structure 30 cubits long and 10 cubits wide (a cubit is the length of the forearm and hand of an adult man). Its walls were made of thick gold-plated acacia wood beams that stood side by side to form three rectangle sides. Long gold-plated wooden poles held the beams in place as they were inserted into interlocking silver sockets. The fourth side was concealed by a hanging curtain. |

| Fabric and animal skin were used to cover it. |

| The wooden structure was draped in a tapestry made of linen and dyed wool in red, blue, and purple. The tapestry was divided into two sections that were joined by a row of hooks. It was covered in goat skin, and its panels were similarly attached with hooks. These two layers covered the structure’s top and hung over the Mishkan’s wooden walls. Furthermore, the roof was entirely covered in red-dyed ram skin and tachash skin. |

| Two altars were present. |

| The Mishkan complex contained two altars. Outside, in the courtyard, there was a large copper altar where many sacrifices were made. Inside, there was a small golden altar where incense was burned every day. |

| It was surrounded by a courtyard. |

| The Tabernacle was located within the chatzer, a large courtyard 100 cubits long and 50 cubits wide. In addition to the copper altar, this area housed the kiyor (laver), which the priests used to wash their hands and feet before performing Divine service. The laver was made from mirrors donated by Israeli women. |

| The outer room. |

| A hanging tapestry divided the interior of the Mishkan in half. Aside from the golden altar, the anteroom known as the Kodesh (“Holy”) housed a number of other items. The golden menorah, whose seven branches the priests lit every day, stood on the southern side. Every week, the priests placed showbread on a golden table near the northern wall. |

| The inner chamber. |

| The Kodesh HaKodashim (“Holy of Holies”) was the name given to the second, innermost room. The ark, a golden box containing the tablets (both the original, broken set and the second, complete set), and other sacred items were housed in the Holy of Holies. Two golden cherubs with outstretched wings faced each other on the ark’s cover. Except for the high priest, no one was allowed to enter the Holy of Holies, and even he only did so once a year as part of his Yom Kippur service. |

| It was inaugurated over the course of 12 days. |

| Moses practiced erecting and dismantling the Mishkan for a week. The Tabernacle was then officially inaugurated on the first of Nissan, just over a year after the exodus from Egypt. The entire tent was filled with God’s presence, as evidenced by a thick cloud that barred everyone from entering, including Moses. The princes of Israel’s 12 tribes brought inaugural sacrifices and gifts for 12 days, the first 12 days of the month of Nissan. The Tabernacle was not just for its stewards, the Levites (priests), but for all Israelites. |

| Six carts were used to transport it. |

| The princes gave the Mishkan several gifts, including six covered oxcarts, one for every two princes. The Gershonites were given two wagons (and four oxen) to transport the Mishkan’s tent coverings and tapestries. The Sanctuary’s wall panels, sockets, posts, and other structural components were transported by the Levite families of Merari using the remaining four wagons (and eight oxen). None were given to the Kehat clan, who carried the most sacred objects on their shoulders. |

| It was located in the center of the camp. |

| Whenever the Israelites camped in the desert during their 40-year journey, the Mishkan served as the focal point of the camp. The Levites, who had been chosen to be God’s ministers, would camp around the Mishkan, while the remaining 12 tribes would camp around them, three on each side. |

| It stood in Shiloh. |

| The Mishkan accompanied Joshua as he led the people into the promised land. The Mishkan stood in Gilgal for 14 years while the Israelites conquered and divided the land. Then they built a stone house in Shiloh and draped the Mishkan curtains over it. Shiloh’s sanctuary stood for 369 years. The sanctuary was relocated to Nov, and then to Givon, at the end of that time period. |

| It was never destroyed. |

| King Solomon built a magnificent permanent home for God on the Temple Mount, outside of Jerusalem, at God’s command. The Mishkan was no longer required at the time. The relics of the Tabernacle were then buried deep beneath the mountain. According to tradition, the Mishkan was never destroyed because it was built with pure intent. It is still waiting for God to return to rest there. |

Additional Reading on the Tabernacle

The tabernacle is mentioned several times in My Jewish Learning’s Torah commentaries on the weekly Torah portions listed below:

Parashat Behar – Weekday Torah Reading (Moroccan TeAmim)